An Analysis of Potential Tax Incentives To Increase Charitable Giving in Puerto Rico

Published on January 27, 2010

Executive Summary

Improved incentives for private charitable donations would strengthen nonprofit organizations that provide a variety of public benefits in Puerto Rico. This study investigates options for stimulating additional charitable giving with enhanced tax incentives. We simulate the effects of proposed modifications of Puerto Rico’s tax deduction on charitable giving and government revenues. Based on our assessment from the economic literature on how individuals respond to incentives for giving, we find that lifting the ceiling on contributions could increase contributions by more than the revenue loss to the Puerto Rico Treasury. Lifting the ceiling would, therefore, be a cost-effective way for taxpayers to pay for additional services of charitable organizations, compared with increasing direct grants. Reforms that modify or eliminate floors on contributions would add less to contributions than the revenue loss, but they would simplify tax filing and could lead to broader participation in charitable giving activities than our simulations imply.

Puerto Rico allows a full charitable deduction only for donations by itemizers in excess of 3 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI). As an alternative, itemizers may elect to deduct 33 per- cent of all donations. Those who give 4.5 percent of AGI or less are better off claiming deductions on a third of all contributions, while those who give more than 4.5 percent of AGI get a bigger tax benefit from deducting 100 percent of contributions over 3 percent of AGI. In addition to the 3 percent floor, there is no deduction allowed for contributions that exceed 15 percent of income.

The fraction of taxpayers in Puerto Rico who itemize deductions is small, compared with the United States, which is in part a result of the constrained incentives, but also may reflect social and cultural differences. Fewer than 10 percent of itemizing taxpayers in Puerto Rico claim charitable deductions, although the average deduction for those who claim is fairly large. I comparison, in the United States, which allows a full deduction up to 50 percent of AGI for itemizers, more than 90 percent of itemizers claim charitable deductions.

Studies by economists of charitable giving strongly support the hypothesis that policies that subsidize additional giving increase contributions. Providing a tax deduction effectively lowers the price of giving so that, for example, it costs a taxpayer in the 33 percent marginal rate bracket only 67 cents to give an additional dollar to a charitable organization. Some studies find the price sensitivity of giving – especially for high-income givers – is so high that the additional contributions induced by the subsidy exceed the revenue loss to the government. This makes the subsidy “treasury efficient” in the sense that it costs the government less to induce private contributions through a tax deduction than it would to give the same amount to the charity with a direct grant.

Even if subsidies to giving cost slightly more than the amount of giving they stimulate, there are still reasons to encourage private giving. These include encouraging volunteering and promoting community engagement, as well as other benefits that flow from subsidies to nonprofit organizations, and allow individual donors to have a direct voice in how some taxpayer funds are spent.

We simulate four options for increasing charitable giving in Puerto Rico. All the changes apply only to taxpayers who itemize deductions:

1. Raise the 15 percent of AGI ceiling on charitable contributions to 50 percent.

2. Allow a full deduction for all contributions in excess of 1 percent of AGI, while eliminating the 1/3 partial deduction for contributions less than the 1 percent floor.

3. Combine options 1 and 2; that is, reducing the floor and increasing the ceiling.

4. Allow a full deduction for all contributions up to a ceiling of 50 percent of AGI (U.S. law).

We also simulate the effects on charitable contributions and revenue of removing the charitable deduction completely, in order to assess the efficiency of current Puerto Rico law. In all the simulations, we use what we consider the best estimates of behavioral responses from the economics literature, although we acknowledge the responses could be larger or smaller.

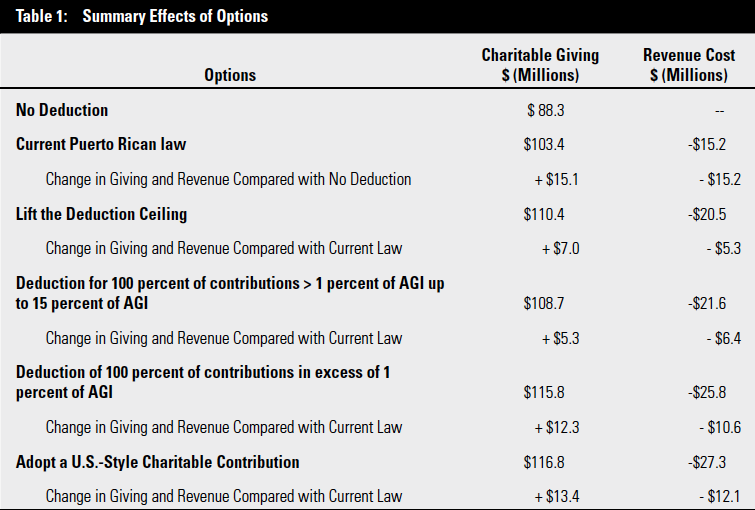

Table 1 summarizes the results of these simulations. We estimate that the current Puerto Rico deduction increases contributions by approximately $15 million at a roughly equal cost to Hacienda of $15.2 million. Raising the ceiling on deductions would cost an additional $5.3 million, but would raise contributions by $7.0 million – an increase of over $1.30 in giving for each dollar of revenue sacrificed. Raising the ceiling is relatively efficient because it provides an incentive for very large donors to give more. In comparison, current law gives large donors a significant rebate for gifts up to 15 percent of AGI, but no additional incentive to give more. Lowering the floor to 1 percent and retaining the 15 percent ceiling, however, costs more ($6.4 million) than the increase in giving ($5.3 million) because it gives rebates for contributions between 1 and 3 percent of AGI by people already giving more than the 3 percent floor.

Shifting to a U.S.-style deduction has the largest impact on contributions ($13.4 million of additional giving), but the largest revenue cost ($12.1 million) of all the options. It would on balance improve the efficiency of the subsidy, but efficiency differences among all the options are not large and the revenue loss would increase. Still, Puerto Rico may want to fund a moderate expansion of its charitable sector. Moreover, by simplifying the calculation of deductions, removing the floors and partial deduction and raising the ceiling may induce more participation and thereby provide even larger net benefits than these calculations suggest.

In addition to changing the incentive structure of the deduction, other changes in the charitable provisions may be called for. In particular, many stakeholders in Puerto Rico expressed the view that it would be desirable to link any expansion of the deduction with measures to improve the accountability of nonprofit organizations in Puerto Rico. One option would be to require organization to register with the IRS as 501(c)(3) organizations as a condition of receiving either any deductible contributions or the enhanced deductions advanced in these options. This could be an important first step towards greater transparency and accountability and help ensure that the revenue loss as a result of enacting these options would go to pay for the activities the subsidy intends to promote.