Europe is under siege. Or at least that is how it feels today, as I write this text. I am far away from Kyiv, but war trickles in, through street conversations around me: at lunch, a business man talks about “damn Putin”, while a taxi-driver curses NATO for not defending Ceuta and Melilla, Spain’s territories enclaved in Morocco, with the same sense of urgency. Ukraine is 2,300 miles away, but the effects of the invasion are slowly being felt in Madrid: the meat industry has alerted about a coming shortage of food for livestock, supermarkets have started to ration sunflower oil, and the cost of the kilowatt hour reached today 71¢ of euro (about .77¢ of dollar). If COVID had made life complicated for us, the Russian invasion has tossed into the air the few pieces that remained in our chess board.

In this Apuntes de Madrid I will try to outline a European perspective about the implications of the conflict in Ukraine. I am aware that events are unfolding rapidly (as I write, the Russian President has threateningly said that economic sanctions seem to be “a declaration of war”). I will attempt, however, to offer context through some of the debates that are being held in European think-tanks and media. Throughout and at the end of the text, I insert links that might be of interest to those that want to continue delving into the topic from this optic.

The End of the Post-Cold War Period

For Europe, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marks a dramatic turning point: the end of what Carnegie Europe analyst Judy Dempsey considers has been a long period of self-deception. It is important to understand that during the last 70 years, European foreign policy has been conditioned by a sort of post-memory anchored on the collective trauma of the Second World War. To a certain extent, Europe as a whole has prioritized humanistic values (democracy, the rule of law, the welfare state) while avoiding the darkest realities of power (the development of a strong military defense component). This has made the European Union (EU) a moral or normative actor in the international arena, but has placed it in what Dutch philosopher and historian Luuk van Middelar considers is a psycho-political limbo, an ahistoric space devoid of real context.

For many decades, the EU and its member states banked on a policy of détente or distension with Russia through its so-called “soft power”, building economic and cultural ties while avoiding an escalation of potential conflicts. Ralf Fücks, from the Center for Liberal Modernity in Berlin, argues that this relationship has a strong emotional component: a mix of guilt (because of the Nazi invasion of Russia), fear (because of the Soviet occupation of the eastern part of Europe and the Cold War), and cultural admiration.

This is why, argues Fücks, in 2008 NATO (at the insistence of France and Germany) denied Ukraine and Georgia’s immediate admission into the alliance (“we should not push the Russians into a corner”); and that in 2014 the European response to the Russian annexation of Crimea was a rather limited one (freeze on certain assets, prohibition on certain imports from the region). John Lough, author of Germany’s Russia Problem: The Struggle for Balance in Europe, says that this also made Europe misinterpret or ignore the increasingly authoritarian and belligerent turn of its Russian neighbor. “I am so angry at ourselves for our historical failure”, said on social media Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Former Minister of Defense of Germany. Until the very last minute, the EU thought that the politics of appeasement and the economic ties – Europe was until the invasion Russia’s main commercial partner and represented 37.3% of its external trade – would function as deterrents for armed escalation and would pave the way for diplomacy and mediation.

The stupor and concern that is currently felt in European capitals cannot be stressed enough. Richard Roberts, editor of the French publication Telos, has said that the Russian invasion of Ukraine implies a return to the Soviet doctrine that culminated in the crushing of the 1968 Prague Spring: a doctrine based in the limited sovereignty of those that share territorial borders with Russia. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has been more categorical: he has said that the invasion shatters the European security system that was forged by the Helsinki Accords after the Second World War. And the Real Instituto Elcano, one of the main Spanish think tanks, has argued that the Russian aggression demolishes the current international order – based in the cooperation among states and the respect for rules – and substitutes it for one based on the imposition of the will of the strongest.

The conflict in Ukraine, then, constitutes a tectonic upheaval for the European Post-War worldview, a defining moment of change. This explains the EU’s determination to finance € 500 million in military armament to Ukraine (a “Hamiltonian” decision because of its centralizing effect, has said El País), the first time that the UE finances arms for a nation under attack. It also explains Germany’s momentous decision to rearm itself and to abandon its historical policy, forged at the end of the Second World War, of not sending armament to conflict zones. Ukraine seems to have become a sort of Rubicon that has pushed Europe into what Politico Europe calls a Zeitenwende, a historical turning point.

The Debate over Europe’s Strategic Sovereignty

The crisis has brought to the fore in European institutions the debate over “strategic sovereignty”, introduced in 2017 by French President Emmanuel Macron (current President of the European Council, which gathers the EU’s elected leaders). The notion propounds a “united and sovereign” Europe capable of acting according to its own interests “on the other side of the Atlantic or on the edges of Asia”. This means having an independent defense capability (in coordination but not limited or subordinated to NATO), the ability to compete economically with China and the USA, the capacity for digital innovation, a harmonized fiscal system, a common migratory policy, robust food security and convergence in social welfare policies. This doctrine has already started to crystalize in Europe’s foreign trade: while the USA is waging a trade war with China, the Asiatic country is currently the main source of imports for Europe (22.4% vs. 11% from the USA) and the third partner for European exports (the USA leads with 18.4% vs. China’s 10.2%). As a matter of fact, China’s medical protection equipment was crucial for the successful management of the COVID pandemic in Europe, after the USA vetoed exports during the initial moments of the pandemic.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has given the defensive aspect of this doctrine of strategic sovereignty a special sense of urgency. Josep Borell, High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy for the UE, has said the crisis has prompted “the birth of the geopolitical Europe”. Since last November 2021, Borell had alerted that “Europe is in danger”, but his words fell flat in the midst of post-pandemic fatigue. His Strategic Compass for the UE – approved in May 2021 by the European Council and about to be discussed by the defense ministers of the EU’s member states – proposes the creation of a 5,000-strong rapid-response UE military force, as well as the development of UE ground, air, sea, space and ciber military capabilities. The question remains if the UE (notorious for its bureaucratic slowness) will be able to act with the celerity and forcefulness with which events are unfolding in the East; and if the European citizenry will trust the UE as much as it has trusted NATO for its defensive security. At the moment, the UE’s defensive system depends on the individual capacity of member states and NATO. NATO, for its part, will hold sometime soon a strategic meeting that will be framed by the scars that the Trump era left in the alliance and the seemingly divergent interests of the allies (Europe is focused on Russia, the USA on China).

Uncertainty and the Costs for Europe

The sanctions will not only harm Russia, but will have economic costs for Europe as well. At a minimum, the Spanish think tank Funcas is anticipating a significant increase in the price of energy, greater inflationary pressures, an erosion of consumer spending capacity, disruptions in export markets and an erosion in investor confidence. The impact will be uneven and may function like a house of cards: Germany is more dependent on natural gas and oil imports from Russia while Spain has a strong component of Russian tourism but depends on Germany for a significant amount of its exports. This uncertain panorama has led Nadia Calviño, Spanish Minister for Economic Affairs, to warn that the war threatens European post-pandemic recovery, propelled by the € 807 billion UE Recovery Plan.

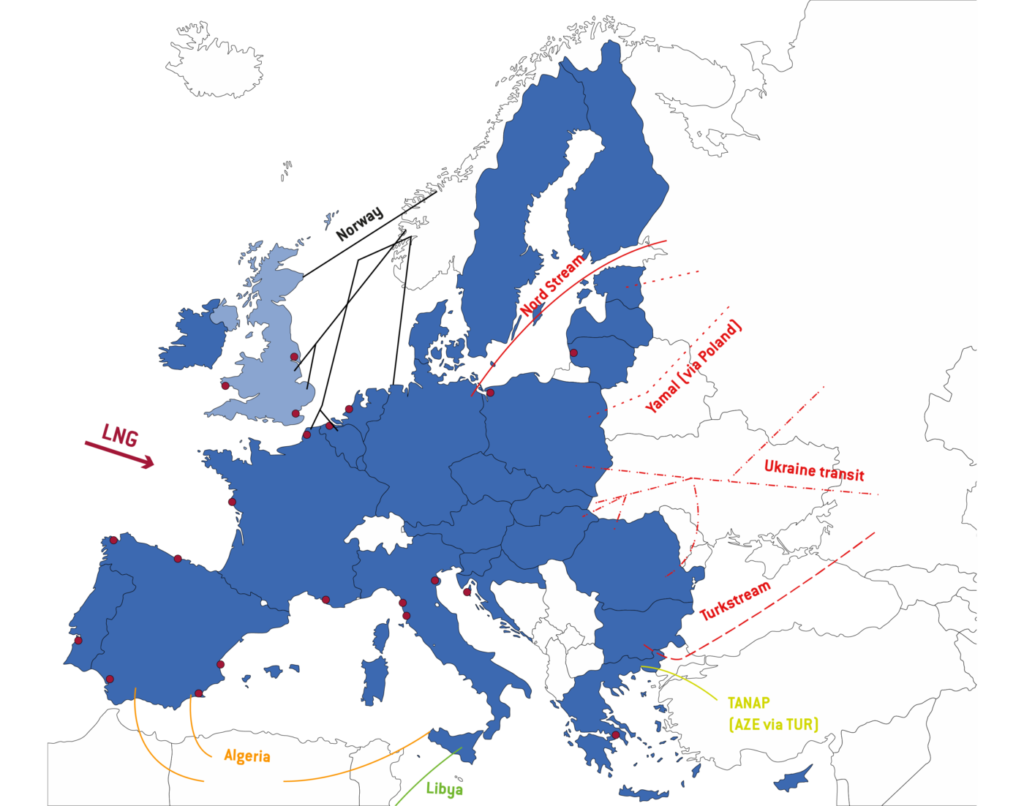

Main routes of natural gas imports into Europe. Source: Bruegel.

Main routes of natural gas imports into Europe. Source: Bruegel.

Energy is the most urgent and critical topic: Russia supplies the EU with 41% of its natural gas imports and 27% of its oil. The EU knows that this energy dependency on Russia is the Achilles’ Heel of its package of economic sanctions: Luis Garicano, economist and member of the European Parliament, has argued that Russia’s expulsion of the financial transaction system SWIFT will only be partially effective as long as Europe continues to import Russian fuels to the tune of € 1 billion a day.

We need sanctions that collapse the Russian state in days, not those that take effect in years. The loophole created by energy payments keeps the Russian economy going. Stopping all trade will save lives and money. In this video, I explain the current impact of sanctions. pic.twitter.com/4X5YBSZytu

— Luis Garicano 🇪🇺🇺🇦 (@lugaricano) March 4, 2022

The transition away from Europe’s dependency on Russian fuel, however, will not be painless: before the invasion, Belgian think tank Bruegel had estimated that an abrupt cut in Russian energy supplies would force a decrease of 10 to 15% in energy demand in Europe, more if weather conditions were unfavorable.

Sources of natural gas imports by country. Source: Bruegel.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has prepared a dossier with measures through which the EU can diminish its dependency from Russian fuels: search for alternative sources (the gas pipeline that runs through Spain could be key in increasing gas imports from North Africa to Europe), an increase in storage capacity to neutralize seasonal fluctuations in energy demand, maximizing other energy sources (renewables, bioenergy, nuclear), and increasing energy efficiency programs. These measures, however, would only achieve a reduction equivalent to 1/3 of annual fuel imports from Russia. The crisis, on the other hand, might bring unexpected silver linings (at a very high cost, though): a reform of the marginalist pricing system of European electrical markets (advocated by Spain since last year’s increases in the price of electricity) and the acceleration of the transition to renewable sources of energy.

Finally, the human cost: the High Commissioner for Refugees of the United Nations estimates that the number of displaced people by the conflict in Ukraine could be as high as 4 million, the largest exodus registered in the continent since the Second World War. More than a million and a half refugees have already crossed the border into the EU, half of them into Poland. Europe had virtually closed itself to refugees since the Syrian crisis of 2015 (in the past years, the dramatic influx of illegal migrants sailing from North Africa has overflowed Spain’s and Italy’s capacity to manage it) but the EU has announced that it will offer temporary protection (residency for 3 years) to those displaced by the conflict in Ukraine. €500 billion has also been budgeted by the EU to manage the human inflow. This change in policy (as dramatic as the turn towards rearmament) has provoked calls for consistency among intellectuals such as the Slovene Slavoj Žižek (in the days following Žižek’s plea, a North African migrant being beaten by Spanish police after jumping the border fence in Melilla has made headlines).

What will be the social and political implications of this tsunami for the EU’s member countries? Will it create more cohesion? Or more polarization? A survey by the European Council for Foreign Relations made in 7 EU countries shortly before the invasion found that a majority of citizens supported Ukraine’s defense through NATO or the EU; support was significantly lower if the defense had to be made by their own country. How will this same citizenry react if the conflict escalates and becomes a prolonged one is still to be seen. Chatham House, an English think tank, found that economic disruptions and immigration flows – elements present in this juncture – are two types of shocks that function as social destabilizers, triggers for both Left and Right populist protest movements. The new era, indeed, is emerging as a quite complicated one for Europe.

Know more:

- Bruegel (Brussels), War in Ukraine: Macroeconomic Implications for Europe (online webinar), March 2, 2020.

- Carnegie Europe (Brussels), Judy Dempsey, Russia’s War Against Ukraine Ends Europe’s Self-Deception, March 1,

- Chatham House (London), Germany’s Russian Policy in the Post-Merkel Era (online webinar), September 29, 2021.

- Die Bundesregierung (Berlin), Policy statement by Olaf Scholz, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and Member of the German Bundestag, February 27, 2022 .

- European Council on Foreign Relations (Berlin), Strategic Sovereignty: How Europe can Regain the Capacity to Act, June, 2019.

- European Council on Foreign Relations (Berlin), The Crisis of European Security: What Europeans Think About the War in Ukraine, February 9, 2002.

- Green European Journal, Richard Roberts, The Return of the Brezhnev Doctrine, March 1, 2022.

- Groupe D’études Géopolitiques (Paris), Luuk Van Middelaar, Europe’s Political Awakening, Working Paper 8, April 2021.

- European Parliament (Brussels), Message by Josep Borell (online video), March 1, 2022.

- Présidence de la République (Paris), Initiative For Europe, Message by Emmanuel Macron, President of the French Republic, September, 2017.

- Real Instituto Elcano (Madrid), Félix Arteaga and Luis Simón, NATO Gets an Update: The Madrid Strategic Concept, January 17, 2022.

- Real Instituto Elcano (Madrid), Ucrania y el futuro del orden internacional (online webinar), February 24, 2022.

- Zentrum Liberale Moderne (Berlín), Ralf Fücks and Marieluise Veck, Russia and the Germans, a Complicated Affair, September 8, 2020.