CNE’s primary and ultimate goal as Puerto Rico’s think-tank has always been to improve the well-being of all those who call this beautiful island home and to increase the opportunities for the generations to come. During the weeks leading to Election Day, CNE will be posing interesting and thought-provoking questions about some of the most important challenges we have in Puerto Rico as part of our Focus 2020 Series.

In this CNE series, our team of experts will take a look at cutting-edge or innovative economic policy ideas on issues such as economic stagnation, the post-Maria reconstruction process, and the roles of the government and the private sector as they relate to economic development.

We are facing many problems but we must come together and focus on the core issues that affect Puerto Rico. Welcome to Focus 2020!

Each week we will add a new topic. Check back on Thursdays to learn more or sign up for the Weekly Review to get updates delivered straight to your inbox.

In this installment, we delve into the roots of Puerto Rico’s current economic challenges. Taking it back to 1945 with the arrival of state-owned firms, past the first phase of the “export-led model” in the 50s, to the upgraded federal tax exemption that drove manufacturing from the mid-70s to the early 2000s, we try to answer the question of how Puerto Rico got to be in the worst economic crisis it has seen since the Great Depression.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

The modern economic history of Puerto Rico begins in the aftermath of the Second World War, perhaps the most destructive conflict in the history of humanity. Europe was in ruins from Normandy to the outskirts of Moscow. The productive capacity of Germany and Japan was decimated. China was about to embark on a civil war. India was still a colony of the soon to be liquidated British Empire. Globalization, understood as the international flow of goods, direct investment, financial capital, and people (with the exception of millions of displaced persons and returning prisoners of war), was at a low point.

Seventy-five years is a long time. Three generations of Puerto Ricans have been born since 1945. But it is important to remember that this de-globalized economy was the context under which Puerto Rico embarked on an ambitious program to modernize its society and change the structure of its primarily rural economy to one dominated by manufacturing.

Initially, the plan was for the Puerto Rican government to directly drive the process by setting up a conglomerate of state-owned firms. This path, however, was quickly discarded after a couple of years and the companies sold to the private sector. It was followed by what was then a relatively novel and ingenious program based on attracting capital from the United States using tax incentives, matching it with Puerto Rico’s surplus labor, and “exporting” the manufactured products back to the United States. Notice, though, this economic strategy was based on advantages that turned out to be temporary or otherwise characteristic of a de-globalized world, namely the lack of other outlets for U.S. capital, the availability of cheap labor, and uniquely free access to the U.S. market.

By some accounts, this “export-led” model, with some later re-tooling, was relatively successful. Puerto Rican economic growth rates soared between 1948 and 1974, with an annual average real rate of 6 percent between 1950 and 1975 and comparable growth in output per worker. Living standards increased as well, as measured by most standard indicators: literacy rates and educational attainment; health outcomes and life expectancy; infant mortality; access to clean water, electricity, and safer housing; and persons per physician all improved significantly.

Yet, by other measures, the structural transformation of Puerto Rico’s economy and society fell short of the mark. Rapid job growth in the manufacturing sector did not replace all the jobs lost in the agricultural/traditional sector and total employment in 1960 was lower than in 1950. The apparent contradiction between rapid growth and relatively high unemployment is explained by a very low participation rate and a large reservoir of underutilized labor. Even with strong internal growth, Puerto Rico experienced a massive out-migration. Over 650,000 persons left the island during the period between 1945 and 1964, out of a total population of 2.2 million in 1950.

One response was the construction of a massive petrochemical complex in the southern part of the island, spurred by a presidential Executive Order that exempted Puerto Rico from U.S. crude oil import quotas. The objective was to move to higher-value-added, capital-intensive manufacturing operations that created high-wage jobs and generated forward and backward linkages with, as well as positive spillover effects in, the Puerto Rican economy.

This plan did succeed in bringing some of the largest firms in the petrochemical industry to the island. Yet it suffered from one unalloyed weakness: Puerto Rico’s new industrialization strategy was based on cheap access to a raw material, petroleum, which Puerto Rico did not produce nor control. This weakness became palpably clear with the OPEC embargo following the Yom Kippur War of 1973. In some ways, Puerto Rico has never fully recovered from the first oil shock, which ended Puerto Rico’s petrochemical dreams.

The times called for a thorough questioning of the prevailing economic strategy but the Puerto Rican government, instead of rethinking the existing economic model and restructuring the productive basis of the economy, simply tinkered with it: obtaining a new federal tax exemption for U.S. firms operating in Puerto Rico (Section 936), increasing government employment, seeking additional increases in federal transfers (food stamps, among others), and issuing public debt in ever larger amounts.

This economic “model” would jumpstart growth in Puerto Rico, but not to the levels seen during the 1950s and 60s. Indeed, between 1975 and 2004, the island’s GDP would grow at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent. Yet by the first decade of the 21st century, it became evident that Puerto Rico’s economic model had collapsed. Section 936 had been phased-out by the federal government; government employment had increased to its upper limits; federal transfers are contingent on the economic and political dynamic in Washington D.C.—and thus could not be the basis of future growth—and public indebtedness was then at historic highs.

Furthermore, those advantages that were specific or particular to Puerto Rico in 1945 had either disappeared, in the case of cheap labor, or ceased to be unique to Puerto Rico, in the case of the dollar, privileged access to the U.S. market, and political stability. At the same time, international trade, investment, and financial flows, as well as migratory movements, exploded. The pressing challenge was to think about how Puerto Rico could insert itself in these global flows. Yet, policymakers in Puerto Rico remained either oblivious to, or willfully ignorant of, this new reality.

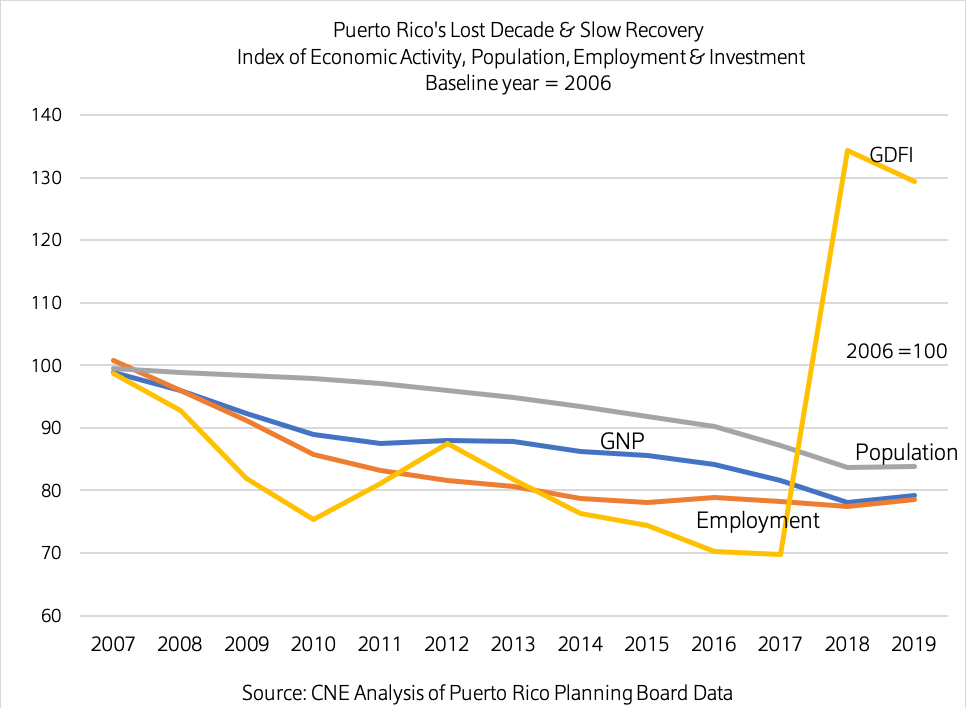

Given this series of unfortunate events, it is unsurprising that in 2006 Puerto Rico’s economy entered a period of sustained decline. As shown in the chart below, real output today is approximately 21% below its 2006 level. Puerto Rico’s government was, understandably, reluctant to cut current expenses – laying off government employees when the private economy was contracting would have left many families without any income, and added to the overall economic woes. But sustaining current spending increasingly required short-changing the pension system and long-term borrowing to cover ongoing budget deficits.

By 2015, Puerto Rico was out of money and out of options. The economy had been in a prolonged secular decline, a depression really, since 2006; net migration to the mainland was increasing, while the natural rate of population growth was decreasing, generating a significant reduction in the island’s population; the government was running chronic budget deficits; tax evasion was widespread, and government corruption proliferated.

At the same time, the island’s government issued ever-growing amounts of public debt just to keep operating. Indeed, between 2000 and 2014 the island’s indebtedness increased at an average rate twice as fast as its GNP. By the summer of 2015, it was obvious that Puerto Rico would not be able to postpone its day of reckoning much longer, it owed $72 billion in bonded debt (exceeding its GNP) and another $50 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. Governor Garcia Padilla acknowledged the obvious and announced to the world that Puerto Rico’s debt was unpayable.

In sum, the Puerto Rican economy was in a deep structural decline prior to declaring bankruptcy and the damage inflicted by the hurricanes, the earthquakes, and the pandemic. And to the best of our knowledge, Puerto Rico is the only jurisdiction to simultaneously go through a debt/fiscal crisis, a reconstruction process after a major natural disaster, and a pandemic. This, dear reader, is the complex background that frames our current economic situation.

This week we want to highlight: CNE’s President, Miguel A. Soto-Class’ remarks about the government’s capacity to administer federal funds and how the institutional collapse will affect Puerto Rico’s opportunities to recover. CNE’s 2013’s most-read column Se acabó la fiesta highlights how we got to the situation we are today. If you want to read about a wider range of major policy issues affecting the island’s economic development, you can read CNE’s The Economy of Puerto Rico: Restoring Growth (2006), a comprehensive economic policy book with analyses of dozens of local and international scholars.

Once upon a time, Puerto Rico had a high degree of state capacity, defined as “the set of skills, capabilities, and resources necessary to perform policy functions, from the provision of public services to policy design and implementation.” (Wu et al, 2018) With time, however, those skills, capabilities, and resources eroded due to several reasons: the dismantling of the professional civil service; the outsourcing and privatization of key capabilities; and years of diminished financial resources due to austerity policies. Yet, even as Puerto Rico faces multiple crises today, its government is being called to execute at a high level. This gap between low capacity and high expectations is perhaps the most important political issue we face right now, yet no one seems to talk about it.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Ph.D. – Research Director, and Sergio M. Marxuach – Policy Director

Between the early 1990s and the Great Recession of 2007, the field of public administration was dominated by theorists who advocated in favor of adopting private sector strategies to “maximize value” in the public sector. (Mazzucato and Kattel, 2020). Among those strategies we find the setting of efficiency targets, outsourcing “non-essential functions”, the privatization of some government services, establishing competition between public and private service providers, deregulation, providing public workers with financial incentives (“skin in the game”), and the deliberate fragmentation of public agencies. The overarching objectives were to make government smaller, more efficient, and hopefully more responsive to the needs of the people.

In many cases, though, the adoption of these policies resulted in an erosion of public-sector capacity to perform its basic functions and in the transfer of significant rents from the public to the private sector. The general decrease in state capacity in countries that adopted these policies came to a head with the global financial crisis of 2008, when it became palpably clear the world economy would collapse in the absence of large-scale state intervention and international policy coordination.

The Great Recession of 2008 prompted a rethinking of the proper role of the state in advanced, as well as in emerging economies. That debate, in turn, has come to the foreground again as the world faces its worse pandemic in a century. In the words of Mazzucato and Kattel:

Tackling grand challenges requires revitalizing private and public investment, innovation and collaboration. It is not about more state or less state, but a different type of state: one that is able to act as an investor of first resort, catalysing new types of growth, and in so doing crowd in private-sector investment and innovation—these are in essence functions about expectations about future growth areas.

Yet, it has been widely reported that the Trump administration’s reluctance to employ the Defense Production Act and other policy mechanisms to “crowd-in” private investment and to coordinate public and private responses to the pandemic in the United States, may have resulted in the loss of thousands of lives. Instead a small clique of advisers around Jared Kushner, mostly management consultants and bankers, blindly advocated for the market “to take care” of ventilator shortages and the lack of personal protective equipment.

Well, in the end, the market failed to work its magic, and state and local governments were left to pick up the slack on their own.

Meanwhile, in Puerto Rico, we have witnessed during the past months incredible situations that make us wonder if the central government of the island has any capacity left to execute necessary initiatives and fulfill basic goals for the benefit of society. The mess with the disbursement of Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (“PUA”) funds, the collapse of the primary vote, and the fact that, three years after the hurricane, only a handful of homes have been rebuilt under local post-disaster reconstruction programs, are just some recent signs of the lack of state capacity.

It is worth noting that increasing state capacity is not an easy task, as it is not just about pulling out a list of new programs and reciting what has worked elsewhere. Achieving improvements in state capacity requires, among other things, transforming the power relations between the state, its agents, and society, and changing patterns and practices that have been entrenched in government for years.

Unfortunately, we find it easier to see and name examples of government incapacity than local experiences that serve as possible role models. But there are interesting examples in places we don’t usually look at. For instance, some initiatives in the mountainous region of the island come to mind: the creation of a consortium between five municipalities that seeks to reactivate a hydroelectric plant and use solar panels to generate electricity; and the municipal case-tracking program to control the spread of COVID -19. Although none of these examples represent comprehensive solutions for our great problems in the energy and health sectors, a closer look will surely reveal some useful clues to address and improve state capacity.

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports:

- Column – Institutional Stagnation – Published on August 17, 2020

- Column – Overcoming Austerity Measures in Municipal Governments – Published on July 6, 2020

- Policy Memo – Oversight that works – Published on August 13, 2019

- Column – Deterioro del estado, inestabilidad y vulnerabilidad – Published on July 30, 2017

- Column – Política industrial en el siglo 21 – Published on September 13, 2015

This week we want, first, to take a step away from the war of federal funding figures and review lessons of the path towards a fair reconstruction. Second, we present a brief summary of how much reconstruction funding has been appropriated, obligated, and spent. Finally, we present a set of questions we believe should be answered as the reconstruction process moves forward.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Ph.D., Research Director

Shortly after Hurricane María slammed Puerto Rico, at CNE we began to study post-disaster reconstruction programs and processes in different parts of the world to identify some general lessons that would guide us on the long and tortuous road to a just recovery. After three long years, during which very little has been achieved and we have had to face new catastrophes, it is worth reviewing some of those lessons that emanate from academic literature (Kates et. Al. 2006; Olshansky, 2006; Olshansky, et. al. 2008) mainly from the experience of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina:

- The reconstruction will be a long, costly, and contentious process.

- Funding is what drives reconstruction, and experience shows that more funding will always be needed.

- Recovery is not a final state, but a process that evolves over time and achieves the most success when local organizations can respond quickly and freely to the specificities of their contexts.

- Lower-income groups and small businesses and, which are often less resilient, need to be prioritized. Because recovery is uneven, higher-income households and businesses usually receive the most attention and can bounce back quicker.

- Recovery efforts should move rapidly to maintain existing social and economic networks, but time should be allotted for sound post-disaster planning.

- Catastrophes provide opportunities to upgrade existing planning systems and reconfigure collaborative links between federal, state, local, and community institutions.

- Government is but one of the players in post-recovery efforts. New organizations emerge and reliable NGOs are often the most efficient and effective respondents.

By Rosanna Torres and Sergio M. Marxuach

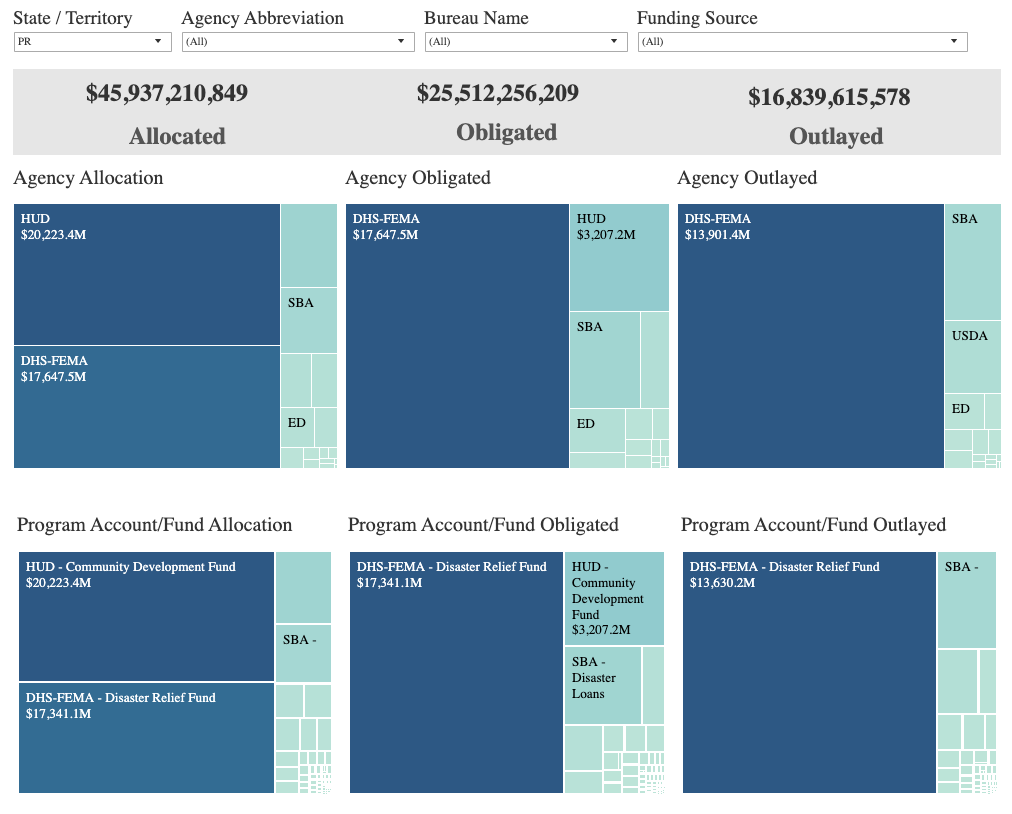

As shown in the chart below, according to the Leadership Group of the FEMA Recovery Support Function, as of July 31, 2020, approximately $45.9 billion had been allocated mostly to HUD ($20.2 billion) and FEMA ($17.6 billion) to address the damages caused by Hurricane Irma and Maria. Of the total allocated amount, $25.5 billion had been obligated mostly by FEMA ($17.6 billion), and a total of $16.8 billion had been actually spent, again mostly by FEMA ($13.9 billion). It is important to note that these amounts do not include emergency nutritional assistance funds and well as supplementary Medicaid funding.

Source: FEMA Recovery Support Function – Leadership Group as of 7/31/20

The table above also does not include the most recent allocation from FEMA. On September 18, 2020, Governor Vazquez held a press conference to announce a multi-billion-dollar allocation from FEMA under Section 428 of the Stafford Act for the Commonwealth. The funding for this program stems from the Disaster Relief Fund. Therefore, although the funding stream is not entirely new, the announcement this week does specifically allocate funding to Puerto Rico’s Electric Power Authority and the Puerto Rico Department of Education, which will be considered “new” funding for the Commonwealth’s sub-recipients. The announcement provides $9.4 billion for PREPA’s permanent work projects and another $2.29 billion for Puerto Rico’s Department of Education to repair and rebuild public schools.

Below we present some questions we think should be addressed by the candidates running for governor of Puerto Rico. The reconstruction process will take at least a decade, probably more. We at CNE believe it is important for the press to ask and the candidates to answer questions about how they envision the reconstruction process evolving during the next four years.

- How can the reconstruction process be made more inclusive? What affirmative actions is the government of Puerto Rico willing to take to increase inclusivity?

- Why is Puerto Rico being subject to higher scrutiny that other jurisdictions undergoing a reconstruction process after a natural disaster? Is the office of the federal coordinator at the White House necessary? How about the monitor for Puerto Rico at HUD?

- How can the influence of pernicious organizations that come “bearing the white man’s burden” be limited in Puerto Rico? How can we increase the effective participation of local NGOs and nonprofits in the reconstruction process?

- Why are contracts being awarded mostly to out of town firms with little or no local connections? What mechanisms are available to increase training and knowledge transfers to the local workforce?

- What mechanisms are necessary to improve cooperation and coordination among and between all the relevant stakeholders?

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports:

- Column – No todo lo que es oro brilla – Published on February 24, 2020

- Dashboard – Federal Post-María Federal Contracting Monitoring Dashboard – Published on October 9, 2019

- Column – The Bureaucracy of Reconstruction – Published on August 15, 2019

- Policy Brief – Puerto Rico’s Unfinished Business After Hurricane Maria – Published October 24, 2018

- Report – Transforming the Recovery into Locally-led Growth: Federal Contracting in the Post-Disaster Period – Published on September 26, 2018

- Column – From Resilience To Resistance – Published July 29, 2018

In the fourth installment of our series, we analyze the land value capture theory as a way to improve municipal fiscal performance.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, Ph.D. – Research Associate, and Deepak Lamba Nieves, Ph.D. – Research Director

Question: How can the central government ensure that municipalities in Puerto Rico are able to overcome their fiscal challenges and provide quality public services and infrastructure?

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing post-disaster reconstruction, municipalities in Puerto Rico are facing increased fiscal constraints and the imposition of austerity measures. In its fiscal plans for the Commonwealth, the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”) has stated that transfers of funds from the central government to municipalities will be phased-out by 2024.

The FOMB is pushing municipalities to simultaneously compensate for this loss of revenue by substantially reforming Puerto Rico’s outdated property tax regime. While property taxation is an essential source of revenue for municipal governments and reforms have been talked about for many years, changes aimed at simply increasing tax revenues can have substantial regressive effects. When these reforms are combined with policies that seek to reduce deficits, they can end up seriously hampering the provision of quality public services and investments. One way to avoid this situation is by focusing on land value capture as part of a broader property tax overhaul.

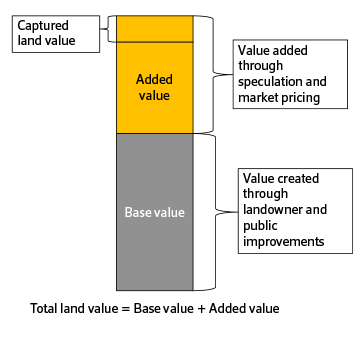

What is land value capture (“LVC”)? As shown in simplified fashion in the diagram below, land value capture refers to a series of policy instruments that a local government can implement to “capture”—through taxation, fees, or acquisition—a fraction of the value that is added to development costs by way of speculation and market pricing. Once the added value is “captured”, local governments can redistribute it by making strategic investments in infrastructure improvements, affordable housing, or public amenities, prioritizing low-income households. Common instruments used for LVC include land value taxation, development impact fees, charges on building rights, community land trusts, and land banking.

TOTAL LAND VALUE AND LAND VALUE CAPTURE

Tools that facilitate LVC are quite common throughout the world, including many countries in Latin America and Europe. In cities like São Paulo, LVC tools provide essential resources for key urban improvement projects. Enrique Silva, director of international initiatives at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, discussed this case in a knowledge exchange hosted by CNE’s Blueprint Housing and Land Initiative. His presentation in Spanish can be accessed below:

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports:

- Initiative – Blueprint: Housing and Land Initiative

- Column – Overcoming Austerity Measures in Municipal Governments – Published on July 6, 2020

In an interview recently published by our friends at Sin Comillas, Professor Edwin Irizarry Mora stated that the current “stagnation, [is] a product of macroeconomic conditions that are still determined by the continuation of the economic depression. This translates into a weak capacity to produce endogenous wealth, with the obvious implications for employment, income, and the production of goods and services. If we add to this the institutional inability — as Dr. Francisco Catalá has insisted so many times — to transform the bases on which our economic system operates, we have the perfect formula to continue in this abyss, with no hope of improvement in the foreseeable future.”

He is right. Even if we set aside the economic harm caused by the 2017 hurricanes, the recent earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear the Puerto Rican economy has been on a path of secular stagnation for at least a decade. This is not to say the reconstruction of the capital endowment damaged or destroyed by the natural disasters, or assisting both businesses and households adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are not important. Those are, however, necessary but insufficient conditions to reignite economic growth in Puerto Rico. As Professor Irizarry Mora correctly points out, we have to work on improving our anemic capacity to produce endogenous growth and on reforming our institutions.

In this installment of our Focus 2020 series, we take a look at how the implementation of a modern industrial policy could help on both fronts: generating endogenous growth and spearheading institutional reforms.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

In the early post-WWII years, industrial policy was defined as any government initiative that (i) stimulated specific economic activities, (ii) promoted structural change from low productivity to higher productivity activities, and (iii) fomented the change from traditional economic activities to more dynamic or “modern” activities.

The traditional case for industrial policy was based on the fact that the world is full of market failures and strong government intervention is necessary to overcome poverty traps. In general, there are two principal forms of market failure. The first type of market failure regards coordination failures, which occur when the return on one investment depends on whether some other investment is made. For example, building a hotel near a beautiful beach may be profitable if somebody builds an airport. Thus, coordination failures are traditionally solved through direct government investments or guarantees.

The other typical kind of market failure regards information spillovers. This occurs because the process of finding out the cost structure for the production of new goods or services is fraught with uncertainty. The first mover will find out whether something is profitable or not, if it is, he will be copied by other entrants, but if he fails, he bears the whole loss. Thus, private returns are lower than the social benefits and the market incentives for these activities are inefficiently low. Information failures usually require government subsidies to promote investment in new industries.

Those kinds of industrial policies have traditionally been subject to several critiques. First, some people argue that government failure is worse than market failure. Governments usually put in place expensive programs and unwieldy bureaucracies that are very difficult to modify or eliminate later on. In addition, these critics say, governments are not good at picking winners because market imperfections are rarely observed directly and industrial policies are usually implemented by bureaucrats that have little capacity to identify where the imperfections are or how large they may be. Finally, bureaucrats are supervised by politicians who are prone to corruption and rent-seeking by powerful groups and lobbies. Proponents of these critiques argue that governments should limit themselves to ensuring property rights, enforcing contracts, and providing macroeconomic stability. The market would take care of the rest.

Well, reality has not been kind to either set of expectations. On the one hand, import substitution, public planning, and state ownership did produce some economic successes, but where they got entrenched and ossified over time they eventually led to colossal failures and crises. On the other hand, economic liberalization, deregulation, and opening up to trade and investment benefited export activities, financial interests, and skilled workers but produced growth rates far short of what was expected; promoted rent-seeking by well-connected economic elites; and significantly increased income inequality around the world.

New Thinking on Industrial Policy

Over the last decade or so, several scholars have challenged the traditional paradigm of industrial policy as limited to activities mostly related to fixing market failures and coordination problems. Indeed, many countries are pursuing innovation-led “smart” growth, which requires certain types of long-run strategic investments. Mariana Mazzucato, among others, argue that “such investments require public policies that aim to create markets, rather than just ‘fixing’ market failures (or system failures).” The countries following this path, have “public agencies [that] not only ‘de-risked’ the private sector, but also led the way in terms of shaping and creating new technological opportunities and market landscapes” while finding “ways in which both risks and rewards can be shared so that ‘smart’ innovation-led growth can also result in ‘inclusive’ growth.” (Mazzucato, 2015)

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to meet one of those scholars who are rethinking the field of industrial policy. Robert Devlin is a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and the co-author of the book “Breeding Latin American Tigers: Operational Principles for Rehabilitating Industrial Policies” (UNECLAC /World Bank, 2011). In this book, Professor Devlin sets forth a comparative analysis of the industrial policies implemented in Australia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, and Sweden; identifies common principles among them; and proposes various ways to implement those principles in Latin America.

First, it is important to clarify that the meaning of the term “industrial policy” has expanded since the early post-war era. It now generally refers broadly to a group of institutions, programs, and public and private organizations working together to achieve an economic transformation in a given country or region.

Furthermore, the objectives of a modern industrial policy are not limited to promoting the transition from a traditional agricultural economy to a modern industrial economy based on manufacturing, but rather it seeks to identify economic sectors, for instance, high technology agriculture, advanced or specialized services, or sophisticated manufacturing, in which a country has an opportunity to create greater added value and thus generate economic growth, as well as new and better jobs.

In this sense, modern industrial policy can be described as a process of discovery and continuous learning that requires close collaboration and coordination between the public sector, the private sector, academia, labor unions and other non-governmental organizations, in order to generate a structural economic transformation in the medium and long term.

Three Strategic Components

According to Devlin, effective industrial policies have at least three elements in common. First, it is necessary to establish a national strategic vision for the medium and long term. Second, effective collaboration with the private sector, broadly defined, is a critical element. And third, consistency in the execution of industrial policy over time is essential for success.

The first component, the strategic vision, in turn requires a deep and intellectually honest analysis of the country’s economic situation, its advantages and disadvantages, areas of opportunity, and the capacity of its institutions and organizations to learn, collaborate, and evolve.

After carrying out this introspection exercise, the objective is to determine the strategic orientation of industrial policy in the medium and long term. Devlin has cataloged four strategic orientations, which are not mutually exclusive: (1) the attraction of foreign direct investment; (2) the internationalization of small and medium-sized national companies; (3) the promotion of exports; and (4) innovation. The capabilities identified in the first part of the analysis in turn determine the strategic orientation of the industrial policy. Thus, we see that some of the ten countries analyzed by Devlin, such as Ireland and Singapore, decided to work on all four strategic directions at the same time, while others such as Australia and Sweden were more selective and decided to focus their resources on only one or two strategic areas.

The second element — collaboration with the private sector — is extremely complex since it requires the capacity on the part of the state to coordinate initiatives and programs, first, between and among the different government agencies in charge of industrial policy and, second, between and among those agencies and the private sector.

In Ireland, for example, the office of the Taoiseach, or Prime Minister, coordinates this work, with the help of a permanent secretariat, the National Economic and Social Council, the National Economic and Social Forum, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment, the organization “Enterprise Ireland”, the Irish Development Agency, Forfás, a kind of government “think tank”, and the Advisory Council on Science, Technology and Innovation, among other agencies. Each of these agencies implements a part of the socioeconomic development plan that is updated every three years.

The state, in addition, must have the capacity to establish a productive collaborative relationship with employers, academics, union leaders, and other organizations. The participation of private sector organizations is very important because, while the state retains the power to implement public policy, it is the private sector that has the knowledge and information about the potential of new opportunities for economic development. However, the state, while establishing cooperation mechanisms with the private sector, also has to ensure the common good and avoid rent-seeking by unscrupulous businessmen or the capture of state institutions by private actors. Executing all these functions is an extremely complex task.

And precisely, the third element is the execution of industrial policy. According to Devlin, it is at this stage that many governments fail catastrophically. A country can design the best economic strategy in the world, but if its state institutions and the private sector cannot execute it, then the effort will not have any significant impact on the economy.

The importance of institutions at this stage cannot be underestimated. Indeed, some scholars argue that it is critical to get institutions “right” before thinking of specific economic policies. According to Dani Rodrik, a first-best policy in the wrong institutional setting will do considerably less good than a second-best policy in an appropriate institutional setting.

Again, it is necessary to think of industrial policy as an interactive process of strategic cooperation between the private sector and government; which on the one hand, serves to elicit information on business opportunities and constraints and, on the other hand, generates policy initiatives in response. The challenge is to find a middle ground for government bureaucrats between full autonomy and full embeddedness in the private sector. Too much autonomy for the bureaucrats and you minimize corruption but fail to provide what the private sector really needs. But if bureaucrats become too embedded with the private sector, then they may end up in the pocket of business interests.

And One More

In addition to the elements set forth by Devlin, implementing a successful industrial policy in the 21st century requires a fair apportionment of both risks and rewards between the state and the private sectors. According to Mazzucato:

Having a vision of which way to drive an economy requires direct and indirect investment in particular areas, not just creating the conditions for change. Crucial choices must be made, the fruits of which will create some winners, but also many losers…This situation suggests that it is necessary for such investments to be made in a portfolio approach with some of the upside gains covering the downside losses. In other words, if the public sector is expected to fill in for the lack of private venture capital (VC) money going to early-stage innovation, it should at least be able to benefit from the wins, as private VC does. Otherwise, the funding for such investments cannot be secured. (Mazzucato, 2015)

In an economic environment where government shapes markets, relying solely on tax revenues may not be sufficient to continually fund a dynamic industrial policy that entails making high-risk investments, many of which will probably fail. Therefore, as Dani Rodrik has suggested, using a portfolio approach to industrial policy means the state should be “able to reap a reward from the wins, in order to fund the losses and the next round. Such direct return-generating mechanisms must be explored, including retaining equity, a share of the IPR, and income-contingent loans.”

Reasons for Failure

Industrial policy can fail due to multiple causes. For example, in some countries the capacity of the state or the private sector to implement a given industrial policy is overestimated. This lack of capacity in turn produces an implementation gap between the plan’s objectives and the economic reality. That gap, eventually, translates into distrust, apathy, and skepticism between the various social actors and the government.

In other countries, the cause of the failure lies in the extreme politicization of the process and in the denial of spaces for participation in the development of the strategy to the political opposition or representatives of other important sectors. It is the participation deficit that eventually causes what Devlin calls the “refounding syndrome” that occurs when a political party comes to power and feels compelled to eliminate all the initiatives of the previous government as it perceives them as illegitimate. A phenomenon with which we are, unfortunately, quite familiar here in Puerto Rico.

Finally, failure can result from the lack of an independent system for evaluating and measuring results. In a process as complicated as this, it is inevitable that mistakes will be made or the potential of an economic sector is overestimated. The important thing is to identify the error in a timely manner, analyze what and why it happened, and promptly redirect resources to other sectors with greater potential.

Traditional Objections in Puerto Rico

When talking about industrial policy in Puerto Rico, two objections immediately arise, both of which are false. The first is that Puerto Rico does not have the political powers or the economic resources to carry out an industrial policy. In fact, Puerto Rico has spent decades negotiating investment agreements with multinational companies and in terms of resources, the consolidated budget already allocates billions of dollars, both in direct spending and tax incentives, for “economic development”. Where Puerto Rico has failed has been in establishing linkages between the foreign and domestic sectors, in enabling the formation of a national production network, and in efficiently coordinating government spending on economic development, which is generally carried out in a fragmented way.

The second objection is that the concept of industrial policy is foreign to the political economy of the United States. This statement could not be farther from the truth. From its inception to the present day, both the federal government and many states have implemented various kinds of industrial policies, either in a formal and structured way or in an informal and tacit way. For example, on December 5, 1791, Alexander Hamilton presented to Congress his “Report on the Subject of Manufactures” recommending an economic policy to stimulate the economic growth and industrialization of the newly created nation.

In more recent times, US industrial policy has been carried out through various agencies, such as NASA, the Department of Defense, and the National Institutes of Health. In fact, many scientific advances, from the creation of the Internet and GPS to basic research in biology and chemistry for the production of medicines, have been funded or subsidized by the federal government. On the other hand, at the state level, almost all states, both large ones like Florida and Texas, and small ones like South Carolina, have developed industrial policies to grow and develop the state economy, and in some cases, the regional one.

Conclusion

In summary, if Puerto Rico truly wishes to straighten the course of its economy, it is imperative to design a modern industrial policy that puts us at the forefront of global economic activity and to create the public and private institutions necessary to implement it.

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports:

- Podcast – Hacia una nueva estrategia de crecimiento económico – Published on June 22, 2016

- Policy Brief – Devising a Growth Strategy for Puerto Rico – Published on June 15, 2016

- Column – Política industrial en el siglo 21 – Published on September 13, 2015

- Column – The Current State of Industrial Policy in P.R. – Published on March 31, 2008

- Presentation – New Tools for Industrial Policy: Proposals for Puerto Rico in the 21st Century – Published on March 12, 2008

The COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on both the economic insecurity that has been affecting workers for decades now — stagnating incomes, dead-end jobs without benefits that pay the minimum wage for years, lack of access to health care, rising inequality — and the deficiencies of the U.S. social safety net. It took many weeks, months in some cases, to get assistance to millions of people who lost their jobs this spring due to the economic impact of the pandemic. And now that assistance is running out, with unemployment still high, a new surge of infections on the horizon, and Congress unable to agree on a new aid package.

There has to be a better way of doing this, many people say. It turns out there actually is a better way. It’s called a Universal Basic Income (“UBI”), an old idea whose time may have finally come.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

The idea of providing a basic income—a universal, regular, unconditional cash payment distributed by the government—is not new. Thomas More mentioned a form of this program in Utopia (1516), while Thomas Paine (Agrarian Justice, 1796) favored a similar program shortly after the U.S. war of independence. More recently, the idea has been favored by those on the right, such as Friederich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Richard Nixon, in the form of a “negative income tax”, as well as by those on the left, such as John Kenneth Galbraith, James Tobin, and George McGovern, among others.

Universal Basic Income – The Ideal

We base our analysis on the “model” or “ideal” UBI described by Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght in their book, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy (Harvard, 2017). Their definition of the UBI is actually rather simple: a universal basic income means “a regular cash income paid to all, on an individual basis, without a means test or work requirement.” Let’s take a closer look at each of these elements.

A basic income, by definition, implies the amount is not enough to survive on by itself. The idea is rather to provide a floor that provides stability when unexpected life events occur, such as unemployment, illness, or a natural disaster, among other similar incidents. This means there is flexibility in designing the program depending on how high a floor a given society deems appropriate.

An individual income means the benefit is provided independently of the household situation. That is, it is irrelevant whether the recipient is married, divorced, widowed, or co-habiting with someone or whether there are children in the household. This has at least three benefits. First, it respects individual autonomy given that receipt of the UBI is not conditional on conforming to any given lifestyle or family structure. Second, it provides a modicum of financial support for people who want to break free from abusive relationships. And, three, it cuts backs on administrative costs, as there is no need to have an army of nosy caseworkers visiting recipients to verify their family status, while liberating beneficiaries from interacting with intrusive bureaucrats.

A cash income maximizes flexibility in using resources, reduces bureaucracy and administrative costs, and “leaves the beneficiary free to decide how to use it, thus allowing individual preferences to prevail among the various options available.” The benefits of cash payments became palpably clear this spring when the federal government provided one-time payments of $1,200 to every person with an income of $75,000 or less. In contrast with in-kind assistance, providing cash meant that people could use it the money to meet whatever need they understood to be most pressing: for example, paying the mortgage, buying medicines, or getting a laptop to allow a child to take school classes from home.

Advocates of providing in-kind assistance argue that providing cash increases the likelihood the money would be wasted. Yet study after study demonstrates that is not the case. Pilot programs since the 1970s in Manitoba, Canada have shown that beneficiaries spend well north of 95% of funds on necessities such as food, healthcare, or shelter. Indeed, that has been the recent experience in the City of Stockton, California, which is running a UBI pilot program.

A universal income means that receipt of the UBI is not subject to an income or means test. This feature of the UBI is controversial because it increases its cost significantly and it means that extremely wealthy people would benefit. Yet, there are good reasons for structuring the program in this way. The first one is philosophical in that universality seeks to eliminate an invidious distinction that has been made since Biblical times between the “deserving” and the “undeserving” poor. The former, usually defined as widows, orphans, and the extremely sick or disabled, were deemed “deserving” of public help as they were poor due to no fault of their own. The latter, however, were deemed to be just lazy vagabonds who did not “deserve” any help unless they were “willing” to work (never mind that sometimes there were no jobs to be had). Hence the creation of that terrible institution known as the “workhouse.” Second, universality removes at least some of the social stigma associated with receiving government assistance as there is no shame in receiving a benefit that is also paid to everybody else.

Perhaps most important, universality addresses what Van Parijs and Vanderborght call the “unemployment trap”. Under traditional means-tested assistance programs, beneficiaries lose part or all of their benefits if they decide to work in even the most precarious job. Facing a marginal tax rate of 100% or more, means many welfare beneficiaries decide either not to work or to work in the informal economy, often under dangerous conditions. In this context, universality means any earnings people do generate go to increase their net income, thus removing a strong disincentive to work associated with traditional means-tested programs.

Finally, an obligation-free income, means there is no obligation for its beneficiaries to work or be available to work on the labor market. This is perhaps the most controversial characteristic of the UBI. Yet, freedom from obligation addresses another “trap” associated with traditional public assistance programs, namely the “employment trap”. Currently, many public assistance programs require beneficiaries to work or engage in “work-like activities”, which means they often end up accepting “lousy or degrading” jobs (Van Parijs and Vanderborght’s words, not mine), offered by unscrupulous employers who know welfare recipients could lose their benefits if they lost their jobs. A UBI program that provides an obligation-free income addresses this potential for exploitation by making it easier to say “no” to unattractive, low-paying jobs.

Some Objections

As the reader can imagine, many objections to the UBI have been put forward by critics from both the left and the right. Here we can only address a few of them, but those interested in a full analysis of the ethical, economic, and political objections to the UBI are well-advised to read Van Parijs and Vanderborght’s book. For those less inclined to do a deep dive into the policy weeds, we recommend reading Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World (Crown, 2018) by journalist Annie Lowrey.

First, poll data shows that many people seem to believe that it is “unfair for able-bodied people to live off the labor of others.” If we assume this argument is made in good faith and is not based on classist stereotypes, then it must be based on some notion of social reciprocity that would be “violated” by people who receive a basic income without working. It would amount to some form of “free-riding”.

At first glance, this argument appears convincing but falls on its own upon closer scrutiny. As Van Parijs and Vanderborght argue, “if one is serious about denying an income to those able but unwilling to work, this denial should apply to rich as well as to the poor.” That is, there is a double standard at work here, one for hedge-fund managers sailing the Mediterranean and another for people who work forty hours a day for the minimum wage. In the acerbic words of John Kenneth Galbraith: “Leisure is very good for the rich, quite good for Harvard professors—and very bad for the poor. The wealthier you are, the more you are thought to be entitled to leisure. For anyone on welfare, leisure is a bad thing.” Second, if we are really concerned about free riding the main worry, according to Van Parijs and Vanderborght, “should not be that some people get away with doing no work, but rather that countless people do a lot of essential work end up with no income of their own”, for example, people who may be in school, taking care of sick relatives, or simply managing their home.

The second objection we want to address goes back to Karl Marx, who opposed schemes similar to the UBI in the 19th century by arguing that it would depress the level of wages because “the bottom constraint, subsistence, has fallen away”. This is not necessarily true, but to understand why we must go back to the universality and obligation-free characteristics of the UBI. The universality condition would make it easier to accept attractive but low-paying jobs such as apprenticeships and internships and thus would tend to lower the overall level of compensation.

On the other hand, freedom from obligation condition allows people to reject low-paying, unattractive jobs. When the demand for “lousy” jobs declines, employers can try to automate them. If that is not possible, they may try to make them more attractive, but where this is impossible or too expensive, they will have to increase the wages they pay. Therefore, “those lousy, poorly-paid jobs which you would not dream of doing will need to be paid better.” The net effect on wage levels, thus, is uncertain. However, the effect on the “worst-paid existing jobs can safely be expected to be positive.” Second, nothing in the UBI is inconsistent with minimum wage laws and regulations.

Finally, the third objection worth mentioning here is cost. A UBI is expensive, quite expensive. However, it is not so expensive as to be unaffordable. First, the total cost would depend on the level of basic income provided. Second, as the program is implemented it will be necessary to increase tax revenue and replace many of the current means-tested programs. This will generate fiscal space for the program. Third, we need to take into account not only the costs, but also all the benefits associated with it, both in monetary and non-monetary terms.

Conclusion

Until recently the UBI was an idea popular only among academics and “the kinds of people who wore T-shirts sporting jokes disguised as mathematical equations. It was something of a fringe interest.” Yet the pandemic changed all that. Indeed, the CARES Act included a partial, temporary basic income in the form of $1,200 payments to people below a certain income threshold and an extra $600 added to basic unemployment benefits.

As we struggle with the economic damage wreaked by the pandemic political support for the UBI may increase. On the “liberal” side, it would mean providing a floor for all people to withstand the economic downturn, while getting rid of “safety net programs that fail to catch many people and in which many others get trapped.” On the “conservative” side a UBI means a hard-budget constraint, few rules, and no new bureaucracies. But perhaps more important, it would allow us to “attack the root cause of troubles for both those who get sick by working too much and those who get sick because they cannot find jobs.” A worthy goal, indeed.

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports, and other resources:

- News article – “Todos estamos a un cheque de la pobreza” – Published in El Nuevo Día on August 30, 2020

- Book – Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy (2019) – By

- Book – Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World (2018) – By

- Book – Raising the Floor: How a Universal Basic Income Can Renew Our Economy and Rebuild the American Dream (2016) – By

In 2016 the federal government decided to establish a fiscal oversight board for Puerto Rico, similar to the one adopted in Washington, D.C., to essentially command all aspects pertaining to government budgeting and spending. We strongly believed back then that imposing an unelected board was not the only option available and that there was another way forward.

Therefore, we presented a series of specific policy proposals that would have laid the groundwork for a broad overhaul of Puerto Rico’s fiscal infrastructure. Our approach was predicated on the notion that a locally-driven effort to overhaul key institutions, and the adoption of a well-designed fiscal rule, could transform Puerto Rico’s fiscal position and introduce much-needed governance reforms to ensure the Commonwealth’s long-term fiscal solvency and sustainability, while addressing legitimate federal concerns and recognizing valid political qualms on the island.

Unfortunately, our proposals fell on deaf ears, as members of Congress, the U.S. Executive, rapacious bankers, and a group of Puerto Rican collaborators successfully advocated for the implementation of the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”) for Puerto Rico.

Four years later, the FOMB has failed to make substantial progress in accomplishing the statutory goals it was mandated to achieve: the few debt restructurings that have been executed have been overly generous with bondholders; little progress has been made to balance the central government budget, and; nothing has happened under the much-touted Title V that would ostensibly “expedite” critical infrastructure projects.

On the positive side, Puerto Rico has been able to (1) benefit from the stay on lawsuits seeking payment on the defaulted debt and (2) finance the cost of providing essential government services using funds that otherwise would have been paid to debtors.

Nonetheless, the enactment of PROMESA has not prevented the filing of dozens of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality and/or legality of actions undertaken by both the government of Puerto Rico and the FOMB. In addition, just as we warned back in 2016, the complex, iterative process instituted by PROMESA to craft both the annual budget and the Five-Year Fiscal Plan has proven to be unworkable in practice and has rendered Puerto Rico essentially ungovernable.

It is in this context that we take another look at our proposal for a fiscal rule for Puerto Rico.

Click the headings below to access our content.

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Ph.D., Research Director

Principal Characteristics of Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Responsibility Laws

Fiscal rules may be broadly defined as mechanisms that allow for the establishment of monitorable fiscal targets and strategies. They have become popular since the 1990s and are currently a common feature in countries throughout Europe, Asia, and Latin America. The desire to establish a permanent institutional mechanism has led in turn to the adoption of Fiscal Responsibility Laws (FRLs). These FRLs vary substantially, as they must be tailored to specific political, institutional, and economic contexts.

Most FRLs include two key features: procedural and numerical rules. Procedural rules usually provide principles for sound fiscal management, reporting requirements, and accountability measures, while numerical rules offer precise fiscal targets that need to be met, most commonly regarding deficits, debt levels, and savings.

Procedural rules help improve institutional weaknesses, increase transparency, and help curb agency problems by increasing voter accountability of public officers. In addition, process improvements may also accelerate the transformation of the overall fiscal environment. Better reporting guidelines and more accurate information, for example, can go a long way to improve the decision-making process of key public agents.

Numerical rules are often associated with reductions in expenditure bias and providing clear targets that limit the discretion of creative budget makers with political biases. But assigning and adhering to hard numerical targets also raises some problems especially during periods of economic downturns when fiscal flexibility is warranted.

The underlying institutional framework that supports the FRL is of utmost importance. Weak or badly designed public financial management (PFM) systems will certainly threaten the efficacy of an FRL. The existence of transparent and accountable practices for preparing budgets, independent monitoring agencies, medium-term fiscal frameworks, reliable accounting, and statistical standards, amongst other institutional requirements, are essential to the efficient implementation of the provisions contained within a FRL. Thus, in terms of sequencing, countries that aim to adopt and implement an FRL should begin by reforming and improving its PFM systems, and gradually introducing procedural and numerical targets.

Finally, strict enforcement mechanisms are crucial to the effectiveness of FRLs. While it is expected that legislators and other public officials monitor compliance, the press and non-governmental watchdog organizations can also play an important role in making sure that benchmarks are met and that sanctions are swiftly applied. In countries with a weak enforcement track record, independent monitoring and oversight may be required. In addition, FRLs require broad political buy-in. If the public agents and political actors who will be at the center of ensuring implementation and monitoring are not in agreement with the law, or do not agree on the need for deep fiscal reforms, then enforcement will be weak and sanctions ineffectual.

Recommendations for a Puerto Rico Fiscal Responsibility Law

We propose that the Commonwealth’s legislative assembly enact a comprehensive Fiscal Responsibility Law with two components: (1) a simple, intuitive, and objective fiscal rule; and (2) procedural guidelines that support a large-scale overhaul of Puerto Rico’s public financial management systems, institutions, and practices.

For the purposes of this analysis, “institutional overhaul” refers not only to particular administrative and management fixes that need to occur within public agencies, but also to broader changes in the legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks that affect social and economic behaviors within Puerto Rican society. As numerous economists have argued, quality institutions (in the broader sense of the term) are central to the task of achieving economic development and growth, in large part because they help shape the different arrangements that support production and exchange.

(1) A Fiscal Rule for Puerto Rico

A well-designed, robust fiscal rule takes into account the cyclicality of government revenues while providing for debt sustainability over the long-term. Therefore, we propose a rule for Puerto Rico requiring that annual General Fund spending shall not exceed (1) cyclically adjusted revenues, as determined and certified by an independent panel of professional economists and other fiscal policy experts, minus (2) a small structural surplus. Within that limitation, the Puerto Rican legislative assembly would assign funds among and between the Commonwealth’s government agencies and departments according to its own spending priorities.

The implementation of this type of fiscal rule has several advantages. First, government spending is by definition limited to its structural income, minus the structural surplus target. Thus, government spending would be independent of short-term fluctuations in revenues caused by cyclical swings in economic activity and other financial vagaries that affect government revenues. Furthermore, this type of fiscal rule would force Puerto Rico to substantially improve its methodology for forecasting government revenues. According to Céspedes, Parrado, and Velasco, “forecasting mistakes, by definition, should be random and short-lived.” In Puerto Rico, revenue forecasts are biased towards the high side on a consistent basis.

Second, according to Velasco and Parrado, this type of fiscal rule, by limiting spending to permanent fiscal income, smoothens out government spending over the economic cycle. In essence, the government saves during upswings and dissaves during downturns. Therefore, the fiscal rule precludes both sizeable spending upswings when the economy is booming and drastic fiscal tightening when there is a substantial economic slowdown. “Hence, the growth of public expenditures becomes much more stable over time.”

Third, the fiscal rule we are proposing requires the Commonwealth to run a small surplus (to be determined as a percentage of GNP) over the life of the economic cycle. This requirement is necessary because (1) Puerto Rico’s debt burden is not sustainable over the long term; (2) the Commonwealth’s government faces potentially crippling contingent liabilities arising out of unfunded public pensions and expenses related to the government healthcare program; and (3) the Puerto Rico Government Development Bank, which provided significant deficit financing in the past, has ceased to exist.

(2) Overhaul of Public Financial Management (PFM) Systems

First, in terms of the budget formulation process, Puerto Rico needs to adopt strategic budgeting practices, namely: implementing performance-based budgeting, utilizing medium-term expenditure frameworks, reforming the current government procurement process that encourages rent-seeking by the private sector, and applying and executing the fiscal rule explained above.

Second, in terms of the budget approval process, the analytical capabilities of the legislative branch need to be substantially improved, perhaps by creating a legislative budget office with the capabilities to double-check and challenge economic and fiscal assumptions utilized by the executive in the preparation of the budget document.

Third, in terms of budget execution, the Commonwealth has to fix longstanding problems with its shambolic accounting, financial and fiscal controls, and with its financial reporting in general.

Furthermore, the agencies in charge of the Commonwealth’s public finances need to establish new procedures to coordinate policies among themselves and to upgrade their operational and execution capabilities, including the hiring of qualified human resources, establishing integrated financial management information systems, and improving internal control, internal audit, and real-time monitoring capabilities.

Finally, Puerto Rico should publish all its past-due audited financial statements as soon as possible. In addition, it has to implement whatever policies are necessary to assure the timely preparation and publication of these audited statements in the future.

Implementing these kinds of thorough transformations does not happen overnight. It is important, therefore, that the Puerto Rico Fiscal Responsibility Law set forth a specific calendar and sequence for implementing PFM reforms, as well as generally accepted indicators and benchmarks to measure progress.

Moreover, proper implementation of the FRL will also require the establishment of an autochthonous, lasting, and independent monitoring body that is embedded within the public island’s fiscal institutional landscape. One that is immune from partisan pressures but can effectively address political considerations and provide the needed technical expertise to address implementation challenges. Having a local commission that ultimately answers to the people of Puerto Rico, will not only provide political legitimacy to this exercise, but can also ensure that experiences and knowledge accumulated over time are effectively internalized within the larger bureaucratic infrastructure.

Finally, these transformations should occur as part of a broader institutional overhaul that also targets the various government agencies focused on establishing and implementing Puerto Rico’s economic development plans and policies.

For more information on this topic check out the following CNE columns and reports, and other resources: