Selected Highlights of the Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022

Published on February 23, 2022 / Leer en español

Introduction

On January 27, 2022, the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”) for Puerto Rico certified a new Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022. The main objective of revising the Fiscal Plan was to adapt it to the terms and conditions set forth in the Plan of Adjustment for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico confirmed by Judge Laura Taylor Swain on January 18, 2022.

In this policy brief, we highlight some of the most important components of the Fiscal Plan.

The Big Picture

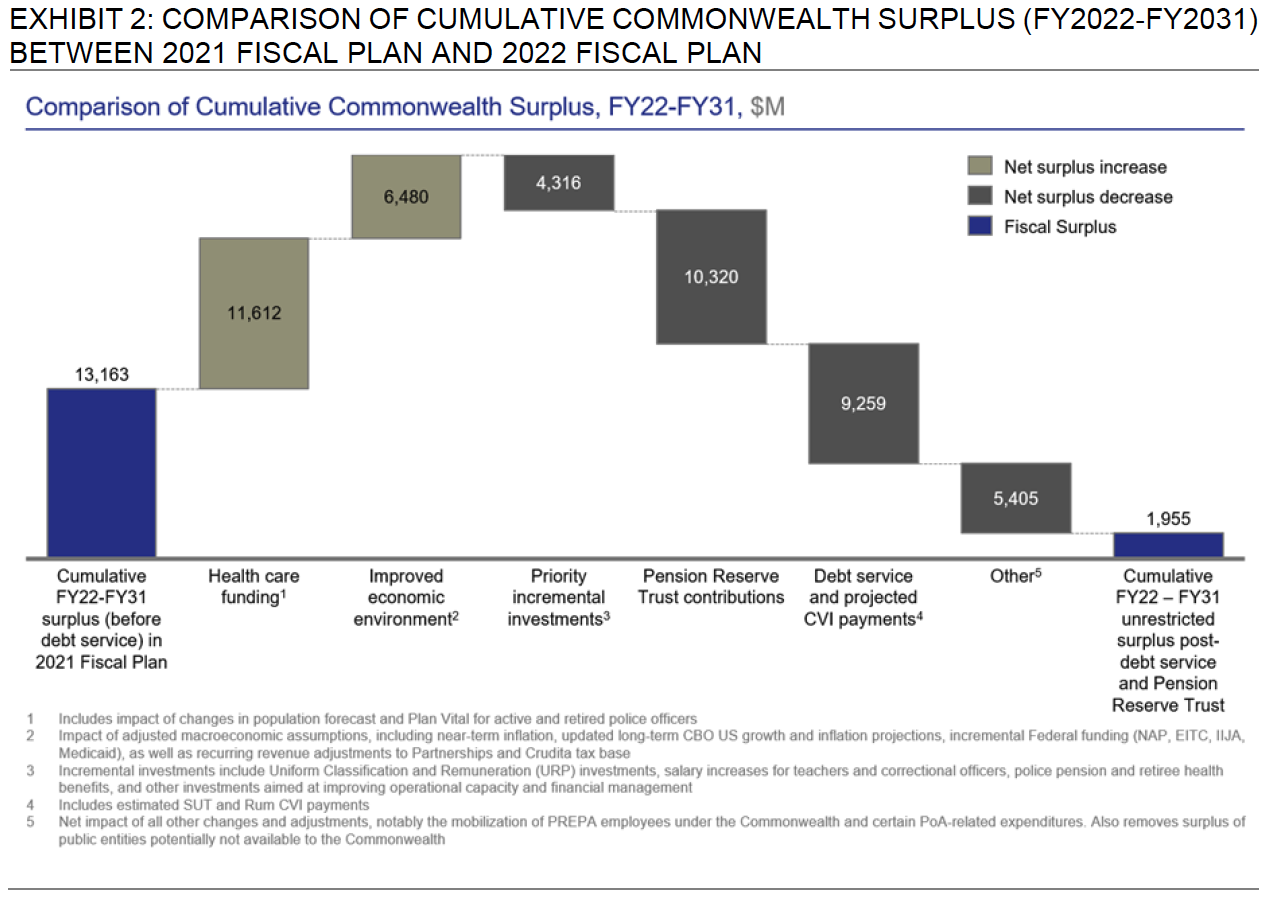

The revised Fiscal Plan includes changes to both revenues and expenses and also includes the debt service on the Commonwealth’s restructured debt according to the Plan of Adjustment. The chart below shows the most important changes to the expected Commonwealth surplus relative to the prior version of the Fiscal Plan in 2021.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 15.

On the revenue side, the most significant changes are an “increase” in federal funding for Medicaid of $11.6 billion during the next ten fiscal years and an additional $6.5 billion from “improved local revenue collections as a result of higher-than-expected overall U.S. growth, increased local consumption and economic activity enabled by enhanced income support programs.”

On the expense side, the largest increase is due to contributions adding up to $10.3 billion over the next ten fiscal years to a new pension reserve trust fund created as part of the agreement with pensioners pursuant to the Plan of Adjustment. We note that these payments are in addition to annual pension payments of approximately $2.3 billion under the current pay-as-you-go system.

The other big change on the expense side is the debt service on the restructured debt and any payments due pursuant to the Contingent Value Instruments (“CVIs”) to be issued on the effective date of the Plan of Adjustment. The FOMB estimates regular debt service and payments on the CVIs, which are made only if revenues from the SUT and rum excise taxes exceed a pre-established benchmark, to sum up to $9.3 billion during the FY2022-FY2031 period.

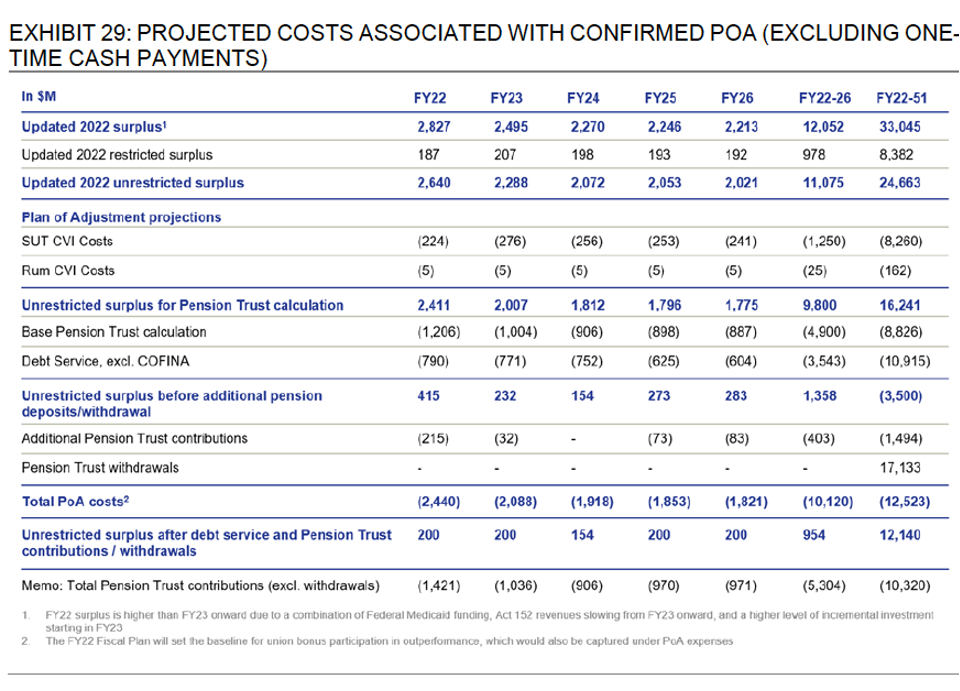

See the table below for a breakdown of the projected costs associated with the Plan of Adjustment.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 71.

Notice that expected unrestricted surpluses at the end of the next five fiscal years are estimated to average $190 million per year. This means the government of Puerto Rico has very little leeway if actual revenues are substantially below expectations, expenses significantly exceed the budgeted amount, or a combination of both lower revenues and higher expenses occurs.

Structural Reforms

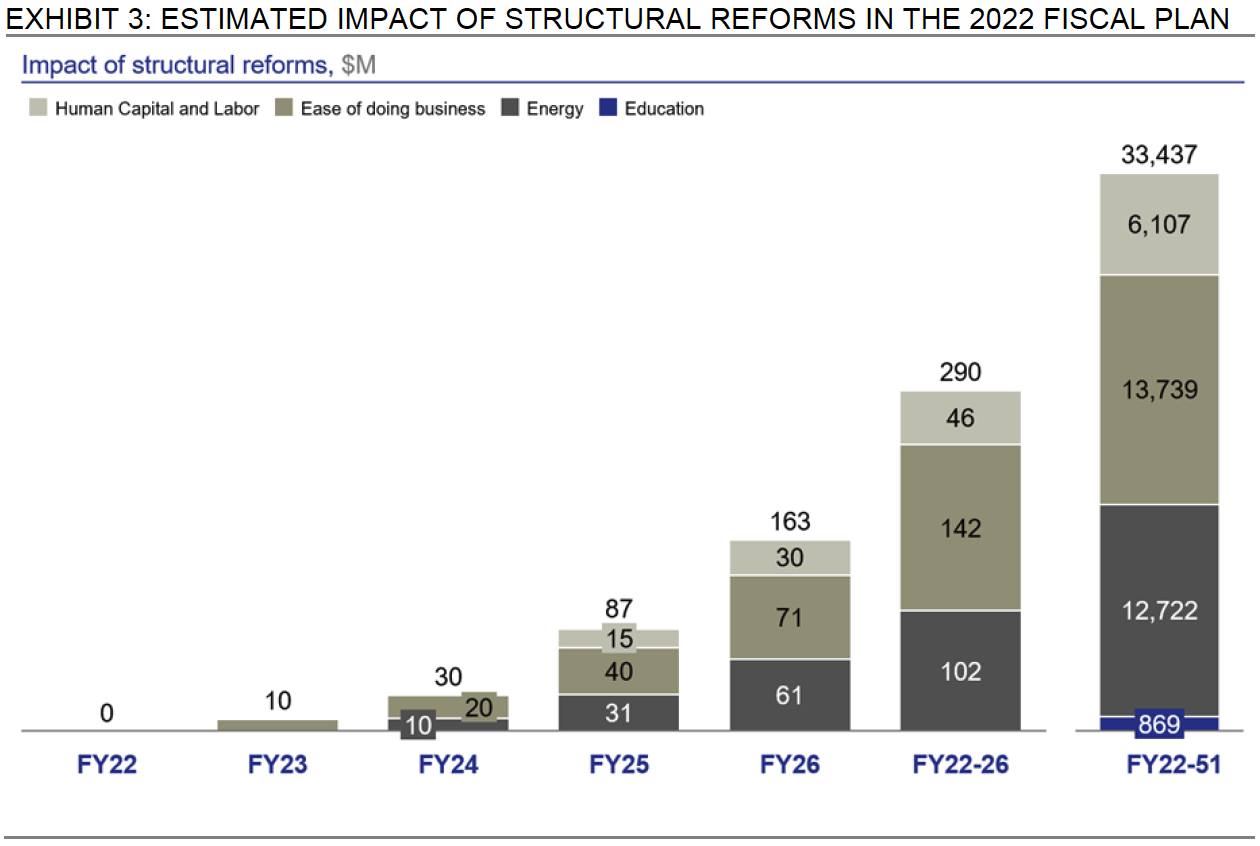

The Fiscal Plan for FY22, just like previous iterations, incorporates the effects of structural reforms in the areas of (1) human capital and welfare benefits, (2) K-12 education, (3) ease of doing business, (4) the power (energy) sector, and (5) infrastructure that, according to the FOMB, “will enable Puerto Rico to begin to grow again based on competitiveness, countering the negative growth trajectory that has plagued the Island for over a decade, and reducing the dependence on federal funds to stimulate economic development.” The chart below sets forth the FOMB’s estimated impact of these structural reforms.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 17.

The problem is that these policies usually do not yield the widespread growth its proponents promise. For example, professor James K. Galbraith in his book, Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (Yale, 2016), describes the European experience with structural reforms in the following terms:

Europe’s economy today makes nonsense of claims that “structural reform” is the key to growth. Structural reform has been tried throughout Europe; it has produced growth nowhere. Granted, the enactments often fall short of the promises; but each shortfall and each failure to show results sparks a call for more reforms—the true mark of fanaticism. The governments that continue to comply do so cynically: in Greece to escape (unsuccessfully, so far) from the bailout; in Italy to strengthen Mr. Renzi’s EU negotiating stance. Very few in countries stricken by structural reforms delude themselves into thinking they will work.

Furthermore, both the IMF and the OECD have concluded that supply-side structural reforms have, at best, a marginal effect on growth, and at worst, no or negative effects on medium to long-term growth rates.

It is highly unlikely, then, that these “structural reforms” will generate the economic growth forecasted by the FOMB’s advisors. Here we would do well to follow the advice of Michael Spence when he said “we shouldn’t slip into the mistake of equating something useful, like financial-sector development or anything else, with a sufficient condition for growth.”

Similarly, we shouldn’t make the mistake of equating a set of quite disparate and perhaps marginally effective structural reforms with an economic strategy. Simply stated, the structural reforms favored by the FOMB and set forth in the Fiscal Plan are second-order issues and will not generate the economic growth Puerto Rico requires, both for increasing the living standards of its people and to pay off its restructured debt, unless they are embedded or framed within a larger economic strategy or vision.

Debt Restructuring

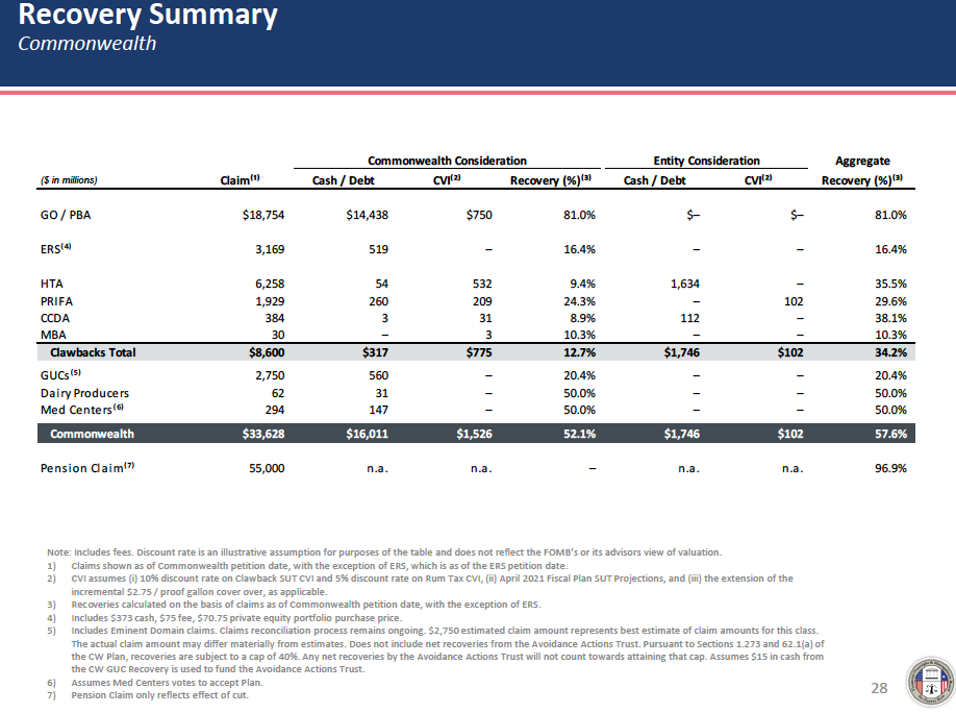

The Commonwealth’s Plan of Adjustment decreases the government’s obligations by approximately 48%, without taking into account potential recoveries through payment on the CVIs. Total debt relief, then, is significant but not as high as the FOMB claims, nor is it as low or trivial as the detractors of the plan allege. The chart below summarizes the debt recovery by creditor type.

Source: FOMB, Plan of Adjustment Overview, p. 28.

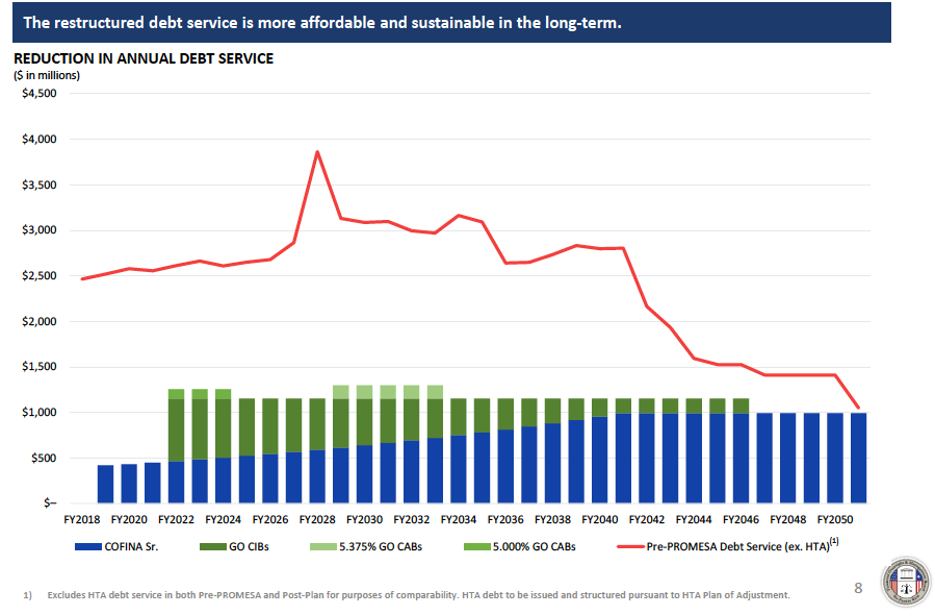

Perhaps more important, from an annual budgeting perspective, the Plan of Adjustment reduces GO debt service considerably, from a pre-PROMESA annual average of $1.33 billion to a post-restructuring annual average of $666 million. As shown in the chart below, total GO/COFINA debt service never exceeds $1.15 billion, or approximately 1.6% of FY21 GNP, during the next 30 years.

Source: FOMB, Plan of Adjustment Overview, p. 8.

The Plan of Adjustment also includes several debt management concepts to limit further indebtedness in the future. These limitations are:

- Maximum annual debt service on all net-tax supported debt is limited to 7.94% or lower than the prior year’s debt policy revenues (basically the general fund plus certain special revenue funds);

- Any new long-term borrowing must be for capital improvements only;

- Newly issued debt must begin to amortize within two to five years of issuance;

- Newly issued debt must have a maximum maturity of 30 years or less; and

- The refinancing of any debt must provide cash flow savings in every fiscal year and produce positive present value savings.

Finally, the 2022 Fiscal Plan “does not anticipate the Commonwealth borrowing for any purpose over the next five years.”

Medicaid

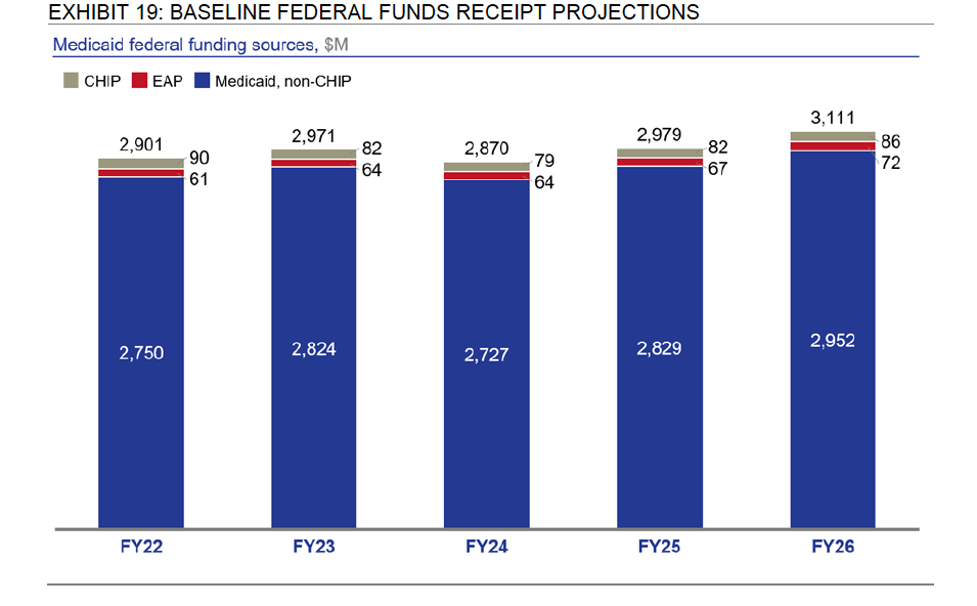

On October 1, 2021, federal funding for Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program was scheduled to revert to its historical level, arbitrarily capped at $406 million for FY22, and subject to a federal matching share of 55%. However, in September 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) issued an interpretation of the Medicaid funding cap provision for Puerto Rico under Section 1108(g) of the Social Security Act that increased the allotted cap for FY2022 to $2.943 billion. CMS further stipulated in this letter that the cap should continue to grow by the medical care component of the CPI-U each federal fiscal year thereafter. The chart below shows the baseline federal funding for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (“CHIP”), and Enhanced Allotment Program (“EAP”) for prescription drug coverage.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 53.

The FOMB considers the CMS administrative interpretation to be a “long-term solution for Medicaid funding for the Commonwealth.” We respectfully disagree. First, the CMS letter is just an administrative interpretation. It is not a binding administrative order, rule, or regulation. It is certainly not a law. Both the GAO and the ranking minority member in the House Energy and Commerce Committee have stated they disagree with the CMS interpretation. Therefore, this policy could be reversed or withdrawn at any time by CMS or it can be overridden by legislation at any moment, especially if the Republicans obtain a majority in Congress after the mid-term elections.

Second, the letter does not change the FMAP, the federal cost share of the program, which is currently set at 55% and can be modified only through legislation. That means that in order to maximize federal funding the Puerto Rican government will be increasing benefits and adding new enrollees into the system. Therefore, if the federal government reverses the CMS interpretation or decides to legislate a significantly lower allotment for Puerto Rico, the Commonwealth government would be in the uncomfortable position of either (1) cutting back benefits or reducing beneficiaries or (2) substantially reducing other spending to pay for the Medicaid program, since the federal share would still be set at 55%.

Finally, the reduction in the amount required to be budgeted by the Commonwealth for Medicaid has “liberated” approximately $800 million which has enabled the legislative assembly to revert to its old profligate ways. In our opinion, those funds could have been put to better use by creating a budget stabilization fund or to restore, at least partially, the General Fund allocation for the University of Puerto Rico.

Pensions

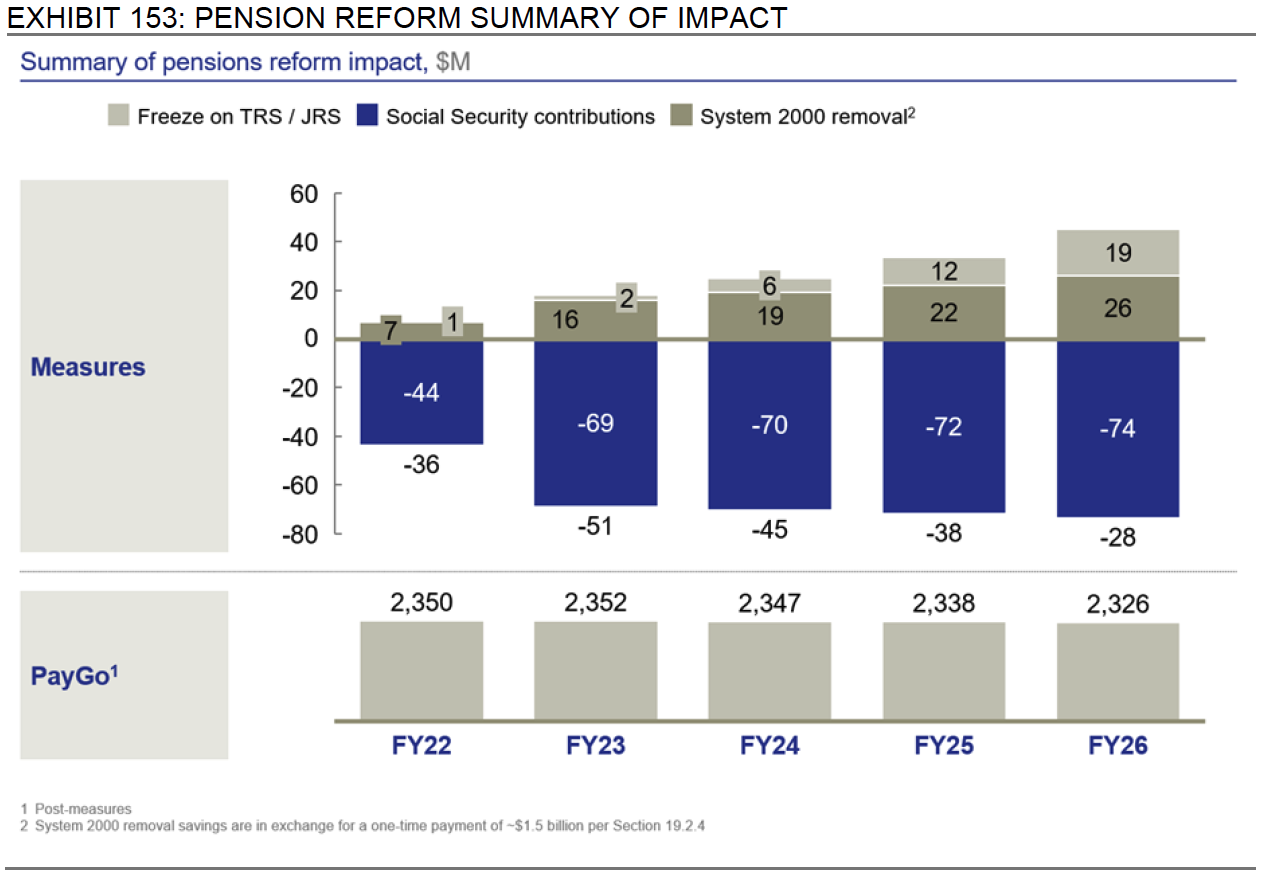

The Fiscal Plan has been amended to reflect certain reforms made to the Commonwealth’s retirement plans. Among these are (1) enrolling certain employees in the federal Social Security program; (2) freezing the existing defined benefit plans currently in effect for teachers and judges; (3) reaching a settlement, resulting in a one-time payment of $1.376 billion, with employees who had accounts under the System 2000 Plan and whose contributions were not duly credited; and (4) budgeting the required funds to make pension payments on a pay-as-you-go basis. The costs/savings associated with these reforms are set forth in the chart below.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 320.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 320.

The Fiscal Plan also provides for (1) the elimination of the proposed 8.5% reduction in the pension benefit of current retirees and (2) the creation of a pension reserve trust “to ensure that future PayGo benefits can be supported regardless of the future economic or political situation in the Commonwealth.”

Funding for the pension reserve trust is to be provided according to a formula based on the Commonwealth’s annual surpluses. The FOMB estimates that those pension trust contributions will average $1.03 billion annually during the next ten fiscal years. Therefore, total pension costs (PayGo plus trust deposits) during the FY2022-FY2031 period will average more than $3 billion per year. This means pension-related payments will be the largest single General Fund expenditure item during this ten-year period.

To be clear, we are not arguing in favor of reducing pensions. We do want to highlight, though, that this $3 billion per year is the cost we are paying now due to decades of mismanagement, for the many years government agencies failed to make the required pension contributions, and for the multiple times that the central government “borrowed” from the retirement fund and never repaid the “loan”.

It is important also to highlight the tradeoffs embedded in the Fiscal Plan. For example, the true cost of the retirement system for FY22 is as follows:

- System 2000 Settlement: $1.376 billion (one time item)

- FY22 Deposit to Pension Reserve Trust: $1.420 billion

- PayGo payments to current retirees: $2.350 billion

- Total for FY22: $5.146 billion

Compare that with a general fund allocation to the University of Puerto Rico of $467 million for FY2022.

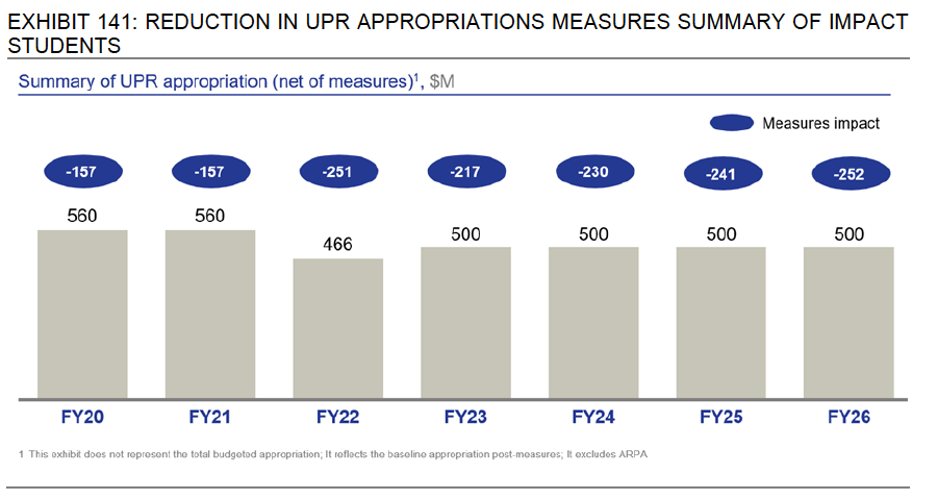

University of Puerto Rico

Perhaps no other government agency’s funding has been cut as much as the budget of the University of Puerto Rico (“UPR”). The UPR’s General Fund allocation has been reduced from $911 million in FY2017 to $466 million in FY22, a reduction of $445 million, or 48%. As shown in the chart below, the FY22 Fiscal Plan includes a modest increase in this allocation from $466 million to $500 million in FY23. General Fund appropriations for the university are then held at a constant $500 million, in nominal terms, thereafter.

Source: FOMB, Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022, p. 301.

It is difficult to understand this massive reduction in the General Fund appropriation for the most important higher education institution in Puerto Rico. Some argue that the budgetary reduction is justified by the reduction in student enrollment. However, a quick look at the data demonstrates this is a false statement. According to data released by the UPR, student enrollment has decreased from 46,325 during fiscal year 2017 to 35,623 during FY22, a reduction of 10,702 students, or 23%. The 48% reduction in General Fund appropriations is, therefore, completely disproportionate to the decline in enrollment.

Furthermore, if the FOMB is really counting on improving human capital in Puerto Rico as an engine for growth in the future, then dismantling the UPR is outright counterproductive. Therefore, we recommend that, if the projected savings in the Commonwealth’s contribution to the operation of the Medicaid program are in fact realized, at least a portion of the funds that become available to the Commonwealth be allocated to the University of Puerto Rico.

Note from the Author

“They Have Learned Nothing and They Have Forgotten Nothing”

The title phrase is traditionally attributed to French statesman Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, in reference to the obdurate behavior of the restored Bourbon dynasty after the fall of Napoleon. After the Revolution of 1789, the subsequent terror of the Jacobins, and the rise and fall of an emperor who sought to conquer half of Europe, the reinstated monarchy pretended to rule as if nothing had happened, picking up things just where they left them in 1789…with predictable results.

In recent times, the phrase has been used to characterize politicians and policymakers who seek to stand athwart history, insisting against all advice and evidence on preserving the disastrous ways of the past, seeking to stop political and economic change at all costs, just to end up repeating the same mistakes of old. History shows such folly can be quite expensive, in terms of both blood and treasure.

Unfortunately for Puerto Rico, we have recently seen a set of political “leaders” demonstrate that they have learned nothing and forgotten nothing since the governor of Puerto Rico declared our public debt to be “unpayable” in 2015. After seven years of default, bankruptcy, federal legislation that stripped away Puerto Rico’s capacity to develop and implement fiscal policy, the imposition of an unelected oversight board, and a prolonged court-supervised process to restructure Puerto Rico’s debt, a group of legislators is acting like they have learned nothing from that experience.

The Puerto Rico Legislative Assembly recently considered House Joint Resolution 278 to implement changes to the current budget in light of the approval and certification of both the Plan of Adjustment for the Commonwealth government and the Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022. Among other things, we have seen the return of pork-barrel politics, the use of non-recurrent funds to cover recurring spending, and the reallocation of funds earmarked for the public health plan based on the mistaken premise that the Biden Administration has devised a permanent long-term solution for funding Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program. They clearly have learned nothing and forgotten nothing.

To be fair, the executive branch is not exempt from this affliction either. Witness the fiscal gimmicks it has implemented to fund a salary increase of $1,000 per month for public school teachers. Just to be clear, we do not oppose increasing the salaries of public school teachers. The Fiscal Plan for FY22 actually included funding for a permanent monthly increase of $470 per month (in two phases). What we oppose, because it is just plain bad policy, is using non-recurring funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (“ARPA”) to top-off the increase to $1,000 per month for only two years. What happens then in 2024? Again, learned nothing, forgotten nothing.

Finally, don’t be surprised if you hear politicians in Puerto Rico start using the phrase “this time is different” in the context of Puerto Rico’s public finances. As Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff state in their book, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, “the most commonly repeated and most expensive investment advice ever given…stems from the perception that ‘this time is different’”. Indeed, the single worst thing we can do as we start to turn the corner out of bankruptcy and the hurricane reconstruction efforts begin in earnest, is to return to the ways of the past, the ways of accounting shenanigans, deceptive budgeting, and unrealistic economic growth and revenue projections, because “this time is different”. It never is.