Policy Director

SHARE

Introduction

Description of the Transaction

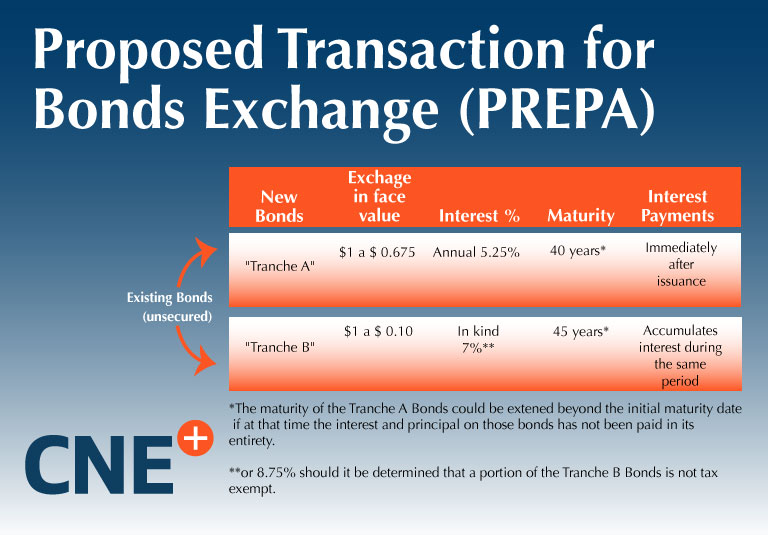

The new bonds would, in turn, be divided into two groups: “Tranche A” bonds and “Tranche B” bonds. Existing PREPA bonds would be swapped for Tranche A bonds at the rate of $0.675 for every dollar of the existing bonds’ face value and Tranche B bonds at the rate of ten cents on every dollar of the existing bonds’ face value.

Thus, a person who owns PREPA bonds with a face value of $100,000 would receive Tranche A Bonds with a face value of $67,500 and Tranche B Bonds with a face value of $10,000, for a total recovery of $77,500, which is equivalent to a reduction of 22.5% in the face value of the existing bonds’ principal.

The Tranche A Bonds would pay interest in cash at a effective annual rate of 5.25% on their face value and would mature in 40 years, while the Tranche B Bonds would offer payment in kind—that is, with the additional issuance of Tranche B Bonds—at a rate equivalent to 7% of their face value (or 8.75% should it be determined that a portion of the Tranche B Bonds is not tax exempt), and would mature in 45 years.

In both cases, the bonds could mature sooner than the term initially established if certain conditions are met. On the other hand, the maturity of the Tranche A Bonds could be extended beyond the initial maturity date if at that time the interest and principal on those bonds has not been paid in its entirety.

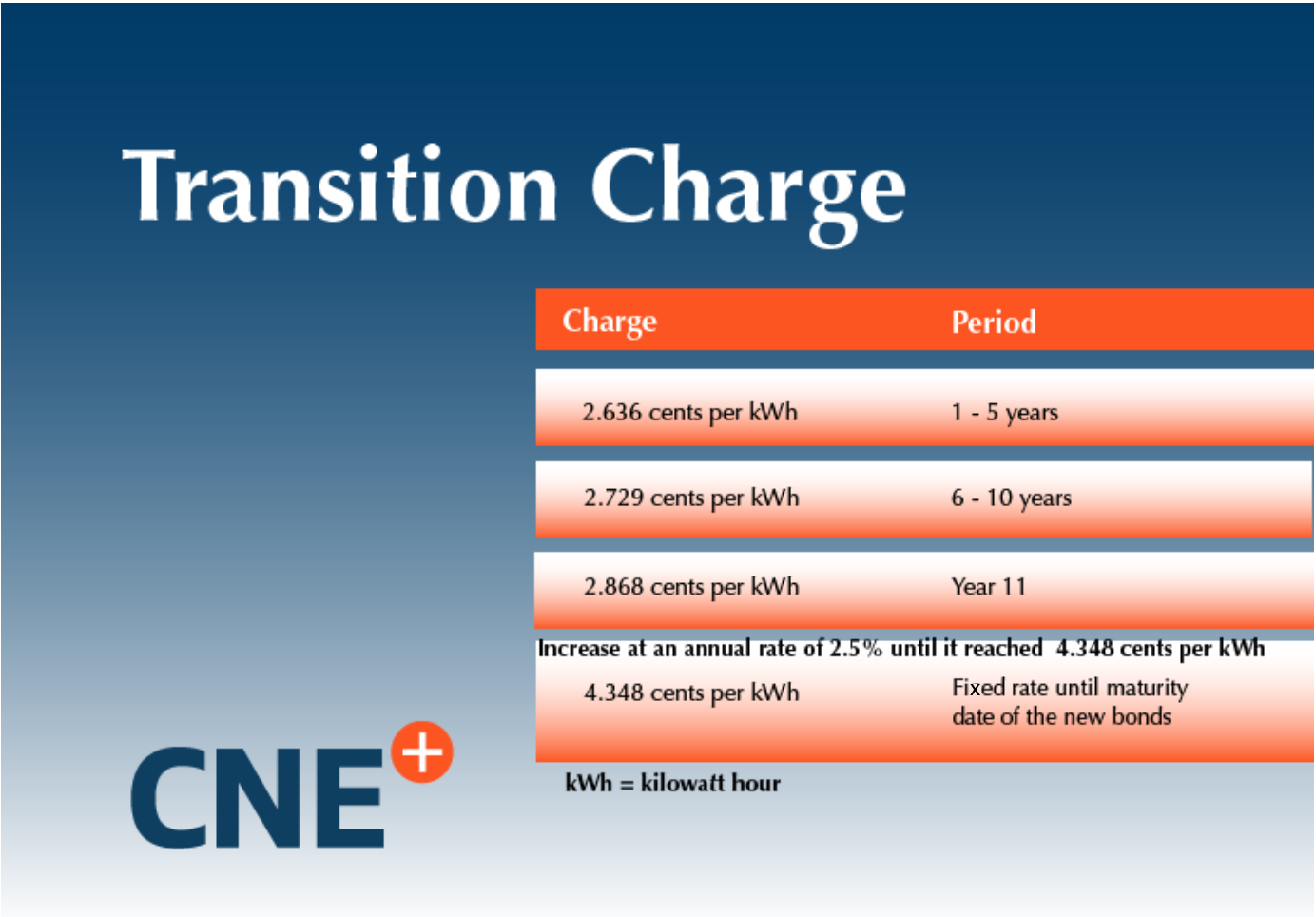

Repayment of the New Bonds

The repayment of both classes of new bonds would be guaranteed with a lien on the future cash flow generated by PREPA, which would be encumbered by the imposition of a Transition Charge. That charge would amount to 2.636 cents per kWh for the first five years, 2.729 cents per kWh for years 6 to 10, 2.868 cents per kWh in year 11, and then increase at an annual rate of 2.5% until it reached 4.348 cents per kWh. At that point, the Transition Charge would remain fixed at that rate until the maturity date for the new bonds.

The Tranche A bonds would begin to accumulate and pay interest in cash immediately after issuance, while the Tranche B bonds would begin to accumulate interest (accumulate only, with payment in kind, not cash) during that same period. Eventually, the owners of Tranche B bonds would receive 100% of the cash flow in excess of the amount required to amortize the Tranche A bonds, but those owners would not be able to recover an amount in excess of (1) the exchange face value plus (2) the cash value of the interest payed in kind.

Non-Payment is Not Default

It is interesting that one of the terms to which the parties agreed, at least in the preliminary agreement, is that bondholders will not be able to declare an event of default should PREPA at some point not make its scheduled debt service payment in full, so long as the revenue generated from the Transition Charge is used in its entirety to pay off the new bonds.

For example, if the debt service for Year X is $100 million, but the Transition Charge generates only $80 million, due, let’s say, to a larger than expected decrease in demand for electricity, the bondholders would not be able to declare PREPA in default so long as PREPA directs the entirety of that $80 million toward debt payment. In exchange for that concession by the bondholders, the bonds would continue to accumulate interest at the agreed upon rate and the maturity date of Tranche A bonds would be extended until they had been repaid in full. But that would not be the case with Tranche B bonds, which in theory could mature even if a portion had not yet been amortized.

Finally, the bondholders who agree to the swap would receive, as an incentive, in exchange for waiving certain contractual rights and supporting the transaction, a fee, payable in the form of Tranche A bonds, equal to 1.72% of the face value of the bonds they exchange. In addition, they would have the right to receive an additional fee, also payable in the form of Tranche A bonds, equal to 0.95% of the face value of the bonds they exchange if certain other conditions are met.

Giving the Principal a Haircut

Much of the public discussion has focused on the amount of the “haircut,” or reduction, to the bonds’ principal, an amount equal to 22.5%. It is difficult, relying solely on information contained in public documents, to determine whether that amount is (1) reasonable and/or (2) sufficient to allow PREPA to continue operating in a sustainable way.

On the one hand, we should remember that PREPA bonds are “special revenue bonds,” which usually enjoy a high degree of protection in municipal bankruptcy cases under Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. These are bonds usually issued by governmental agencies that provide such basic services as transportation, water, sewers, electricity, gas for heating, and so on. The repayment guarantee for these bonds, as is the case with the existing PREPA bonds, is a lien against the net revenues (after paying the operating costs of the issuer) generated by the issuer.

According to James E. Spiotto, an expert in municipal bankruptcies and author of Municipalities in Distress?: How States and Investors Deal with Local Government Financial Emergencies, Congress amended the Bankruptcy Code in 1988 specifically to make it clear that revenues encumbered on behalf of this type of bondholders could not be diverted for other purposes, and that those bondholders had the right to continue receiving their payments—again, I stress, net of the issuer’s operating costs—even after the debtor had filed for bankruptcy. Therefore, these bonds are not as a general rule substantially modified, if at all, in a case under Chapter 9. Thus, we might say that in comparison with other bankruptcies by similar entities in the United States, the 22.5% reduction in the principal is reasonable.

However, PREPA is not in a process under Chapter 9, even though Title III of PROMESA incorporates many of the provisions of that Chapter in its Section 301 (a). Therefore, the FOMB may have more leeway to negotiate a restructuring of PREPA’s debt. In addition, in the case of PREPA, we must take the following factors into account: (1) it operates in an economy that has shown no growth in years; (2) its administrators have negligently postponed maintenance on its generation plants and its transmission and distribution lines for decades; (3) the demand for electricity is projected to decrease over the next few years; and (4) PREPA needs a massive injection of capital in order to modernize and optimize its operations.

Given those factors, the haircut of 22.5% to the principal of the existing debt may not be sufficient to allow PREPA to continue operating in a sustainable way. That may be the explanation for the bondholders’ having agreed to waive the right to declare PREPA in default in case of a non-payment. It appears that the parties to the agreement are assuming from the outset that there is a high probability that PREPA will not be able to honor the negotiated terms and conditions, and so have agreed on a mechanism beforehand to mitigate that risk.

In fact, the documents related to the preliminary agreement do not reveal how the determination was reached that that amount of debt relief is the amount required to allow PREPA to continue operating. The Fiscal Plan of August 1, 2018, also does not explain or take into consideration debt service beyond stipulating that the amount of the existing debt is not sustainable (see page 27 of the Fiscal Plan of August 1, 2018). Nor do any of the projections laid out in the Fiscal Plan include analysis of how electricity rates would be affected in a post-debt-restructuring scenario. In our opinion, it appears that there is a disconnect between the Fiscal Plan’s scenarios and what is set forth in the preliminary agreement with the bondholders.

Therefore, with the information available at this time, we cannot determine with any certainty whether the proposed reduction in the principal represents the amount needed to maintain the corporation as a going concern.

Transition Charge

Another issue that has captured the public’s attention is the Transition Charge. That debate has centered on trying to determine whether the charge is or is not a rate increase. In theory, as some government representatives argue, the charge would not necessarily entail a rate increase for customers, so long as PREPA reduces its operating costs by an amount equal to or less than the charge. In practice, achieving that reduction would be very difficult—although not impossible.

For example, on the most recent electric bill I received from PREPA, I was charged 21.41 cents per kWh. The Transition Charge for the first year would be 2.636 cents per kWh—12.3% of the price that PREPA billed me for on that statement. Under normal conditions, it might be feasible to achieve a reduction in operating costs in that amount.

But we are not operating under normal conditions. As I argued before, the economy is in depression, the demand for electricity is decreasing and is projected to continue decreasing. And according to the Fiscal Plan, PREPA needs to make a series of capital investments in order to reduce its dependency on oil and reduce its operating costs, and those investments have to be financed in some way.

In specific terms, the Fiscal Plan projects a reduction in the price of fuel of approximately 25% between 2018 and 2025. We do not believe that premise is particularly reasonable. And hidden in a footnote is the fact that those savings depend on a capital investment of approximately $2.9 billion in new generation (Fiscal Plan, pages 43 and 44). Also unanswered is the question of who would finance that investment in new generation capacity. Given those circumstances, it seems to me that achieving those savings is highly unlikely—although, I repeat, not impossible.

Effects on Privatization

Perhaps more important that the foregoing debate is that neither the transaction’s Term Sheet nor the Fiscal Plan certified by the FOMB explains how that Transition Charge was calculated or to what volume of sales of electricity it would be applied. This latter point is extremely important because it could affect the proposed transformation of the transmission and distribution network.

For example, if the charge is applied only to the production of electricity by PREPA’s generation assets, then bondholders would have an incentive to discourage new generation assets (such as solar and wind energy) from coming on line. If it is applied to all the energy transmitted by the network, then bondholders would have an incentive to discourage PREPA customers from disconnecting from the network as a result, for example, of investing in their own microgrids. If it is applied to all customers, even those who have disconnected from the network, then it would discourage customers from investing in and building private microgrids. Thus, it is imperative that additional information be provided about how the Transition Charge would work and that an analysis be carried out of how the charge’s imposition would affect economic incentives or limit the feasible options for transforming the transmission and distribution network.

In addition to all this, there are many questions left unanswered. For example, what is going to happen to the bondholders holding bonds insured by companies who insure financial instruments? Will the same terms and conditions be offered to those bondholders, or will another transaction be negotiated? Will the Transition Charge be collected from all customers, including municipalities and those customers who receive subsidies? Will the Puerto Rico Energy Commission have to analyze and approve both the bond exchange transaction and the Transition Charge? How will the proposal to transform PREPA be affected in the light of this transaction with the existing bondholders?

Conclusion

In sum, the proposed transaction constitutes an important first step in the transformation of PREPA, but there is much important information that we still need to determine whether the proposed transaction is in the best interests of the people of Puerto Rico.