Published on April 20, 2020 / Leer en español

Special Edition: The Paycheck Protection Program

This special edition contains analysis from Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, Malu Blázquez, Rosanna Torres, Nuria Ortiz, and Sergio Marxuach.

Background

On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act or the Act) (Pub. L. 116–136) to provide emergency assistance and health care response for individuals, families, and businesses affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The Small Business Administration (the “SBA”) received funding and authority through the Act to modify existing loan programs and establish a new loan program to assist small businesses nationwide adversely impacted by the COVID–19 emergency. Section 1102 of the Act temporarily permits SBA to guarantee 100 percent of 7(a) loans under a program titled the ‘‘Paycheck Protection Program’’ (the “PPP”). Congress authorized funding of $349,000,000,000 to provide guaranteed loans under this new 7(a) program.

According to the official SBA guidance, the following entities could be eligible for PPP loans:

- “Any small business concern that meets SBA’s size standards (either the industry based sized standard or the alternative size standard);

- Any business, 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, 501(c)(19) veterans organization, or Tribal business concern (sec. 31(b)(2)(C) of the Small Business Act) with the greater of:

- 500 employees, or

- That meets the SBA industry size standard if more than 500;

- Any business with a NAICS Code that begins with 72 (Accommodations and Food Services) that has more than one physical location and employs less than 500 per location; and

- Sole proprietors, independent contractors, and self-employed persons.”

Furthermore, Section 1106 of the Act provides for forgiveness of up to the full principal amount of qualifying loans guaranteed under the PPP. This is perhaps the most attractive feature of the program. If loans are used to cover payroll costs; continuation of health care benefits and insurance premiums; employee salaries and compensation; rent; utilities; and/or interest on any debt obligations incurred between February 15, 2020 and June 30, 2020, they are eligible for forgiveness – so long as borrowers maintain staff and refrain from reducing employee compensation by more than 25 percent. Otherwise, the total amount of loan forgiveness will be reduced.

However, in order to incentivize businesses to maintain employees, if staff cuts or salary reductions were made between February 15 and April 26, the law allows borrowers to restore full-time employment and salary levels. The law also adds flexibility in its requirements under traditional SBA loans. For example, administrative fees, personal guarantee, collateral, and credit elsewhere requirements are waived.

What Was It Intended To Do?

Lawmakers expected to provide temporary economic relief to small businesses and nonprofit organizations suffering from the economic fallout due to COVID-19. But simple math demonstrates the money was never going to be enough. Instead, its first-come, first-served structure created a rat race for eligible applicants.

It was clear that if each of the 30.2 million small businesses in the United States applied for the maximum loan amount (payroll costs for 2.5 months) the $349 billion in initial funding would not be enough to satisfy the needs of other applicants. Money would eventually run out (and it has). Who would benefit most? Who would be left out? Those are the numbers we are beginning to see.

Finally, the Congressional intent was for the appropriated money to flow quickly to small businesses, so the application process was to be, at least in theory, flexible and expedited, requiring only basic, really minimal, credit and background checks. In exchange for that, and filling out some papers, lenders were authorized to charge fees of up to 5% of the loan amount. The fee percentage was set to decline if loan amount increased above certain thresholds.

Implementation of the PPP

The rollout of the PPP had some glitches. The Treasury Department was late in issuing the guidelines and rules for the program. It took banks some time to understand the new rules, implement internal systems for receiving and processing applications, as well as to disburse the funds in compliance with the PPP rules. Borrowers in many instances were not familiar with the requirements or faced problems submitting applications to their banks. According to some press accounts many borrowers never heard back from their lenders until it was too late and it appears thousands of applications were never even properly considered.

Notwithstanding the implementation problems with the PPP, the approximately $350 billion in funding for the program was exhausted in less than two weeks., which is good, given the state of the economy. It also underscores one of the structural problems with PPP: it was severely underfunded from the start and demand far outstripped supply.

Initial Results

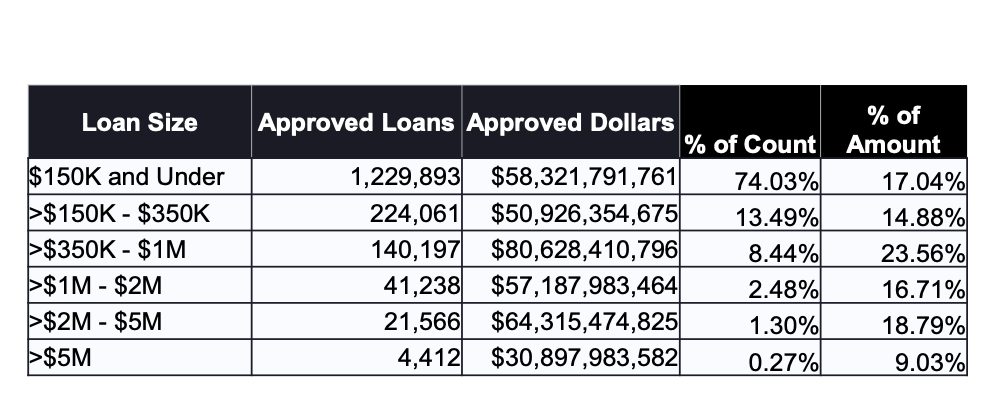

According to data published by the SBA, as of April 16, 2020, some 4,975 lenders had approved 1,661,367 loans in an aggregate amount of $342,277,999,103. The average loan amount was $206,021. Seventy-four percent of all approved loans by count were in an amount of $150,000 and under; while approximately 45% of loans by amount were in excess of $1,000,000. This means, as shown in the table below, that only 4% of all loans accounted for approximately half of the total loan amount approved.

Which leads us to the second structural flaw in the program: there were no guardrails to prevent banks from favoring relatively larger businesses within the small business pool, enterprises that in all probability already had other outstanding loans with those same lenders.

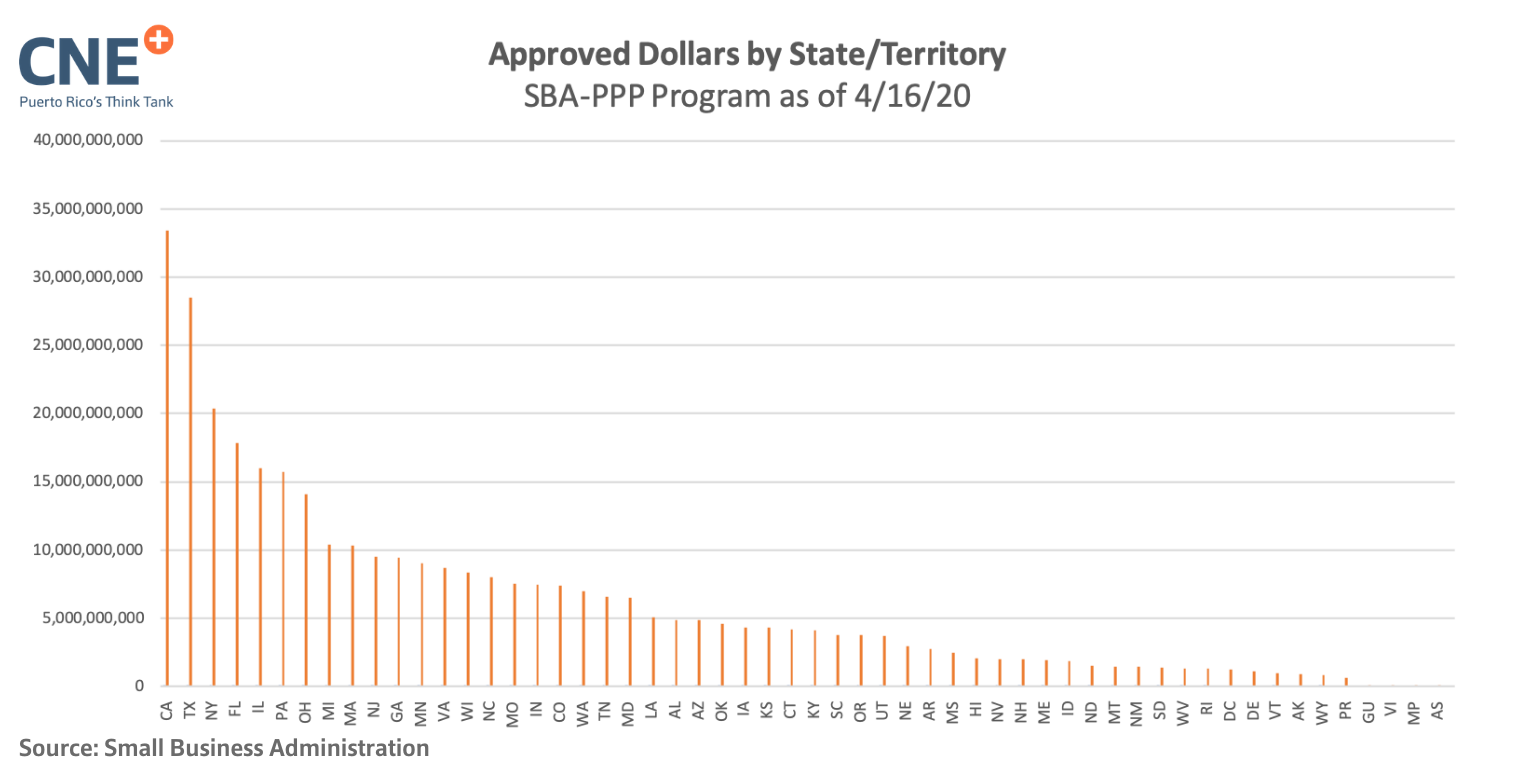

In terms of geographical distribution, as shown in the graphic above, the results were basically as expected. The bulk of the dollars went to the larger states, with small businesses in California, Texas, Florida, and Illinois receiving the largest amount of dollars approved.

Impact of the lockdown in Puerto Rico

The Puerto Rican economy has been battered, just like in the mainland, by the COVID-19 pandemic, if not more given the devastation caused by Hurricane Maria in 2017 and a string of earthquakes earlier this year. Shutdown orders to contain the spread of the coronavirus have forced many businesses to halt operations and left workers out of jobs. But the impact is not the same across all industries.

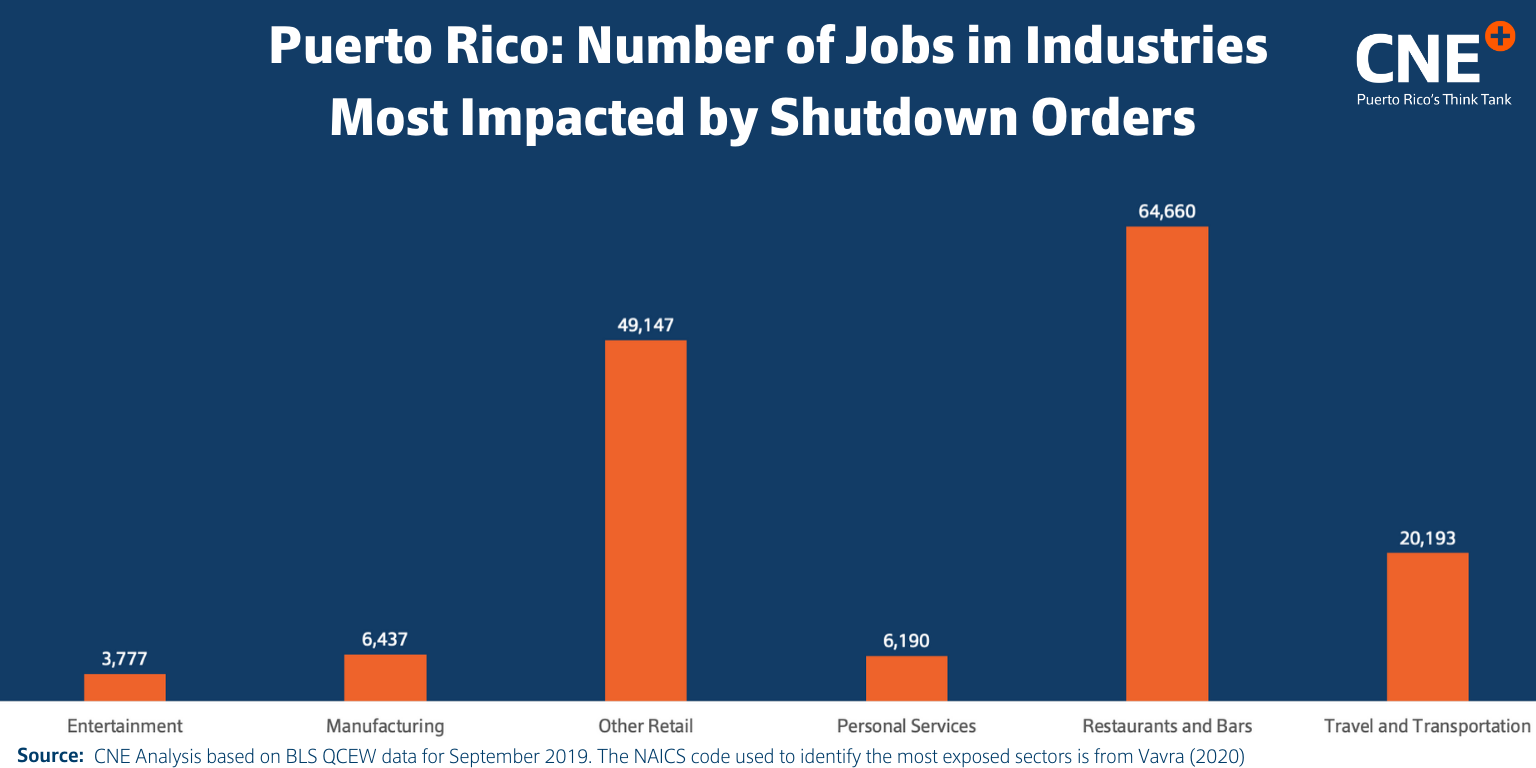

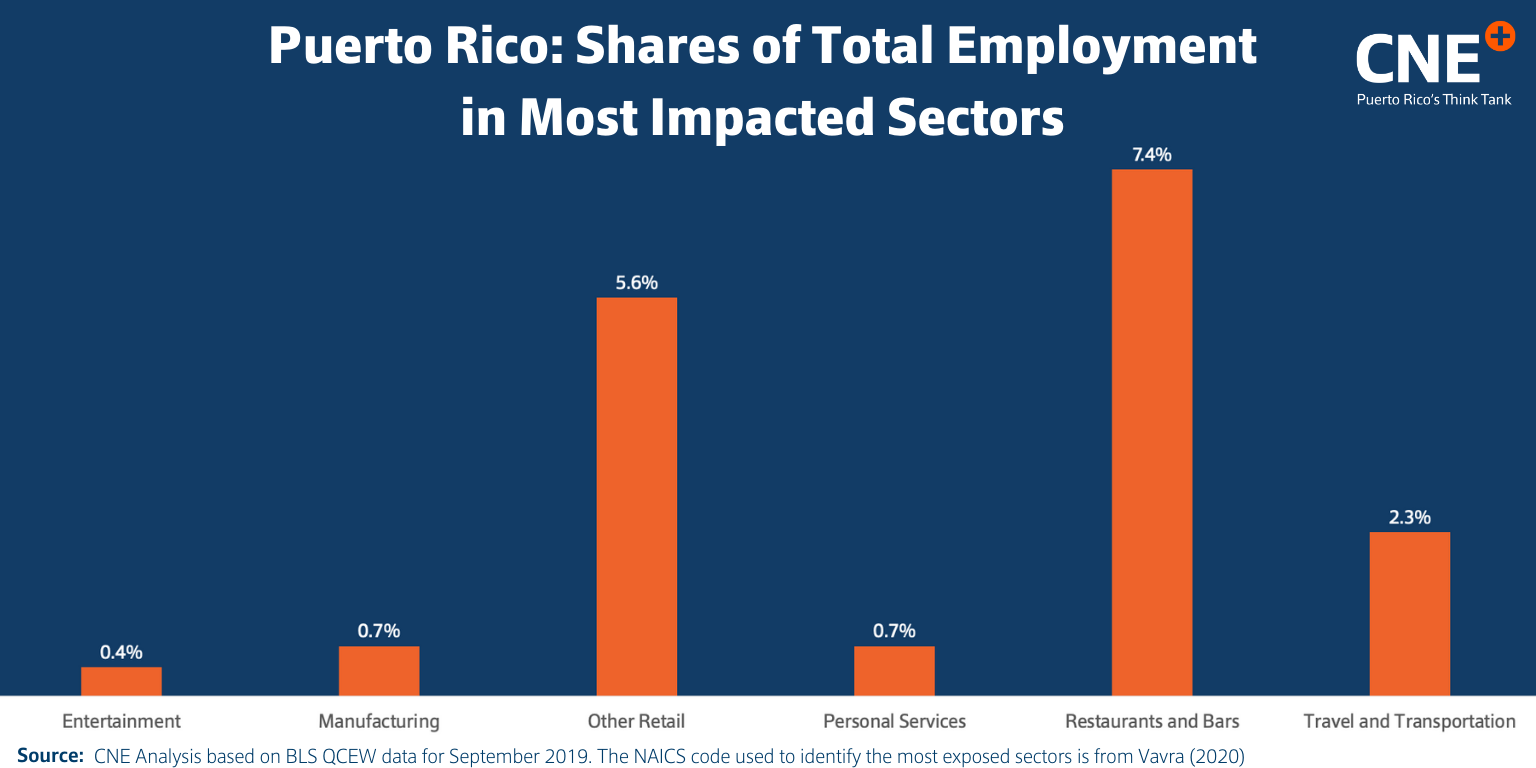

To figure out which sectors and how many workers in Puerto Rico are impacted by these measures, we analyzed third quarter 2019 data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), and employed a methodology devised by Professor Joseph S. Vavra from the University of Chicago. Vavra identified six sectors that are most “exposed” to shutdowns, these include: Travel and Transportation (i.e. travel accommodation, taxi and limousine, air travel, etc.), Restaurants and Bars, Entertainment (casinos, spectator sports, etc.), Personal Services (barbers, beauty salons, dentists, etc.), Manufacturing (office furniture, vehicle parts, etc.) and Other Retail (clothing, luggage and jewelry stores, etc.). Vavra’s initial analysis was replicated and expanded by the BLS.

Our analyses indicate that, in September of 2019, over 150,000 employees were in the most affected sectors. As the figure above indicates, the bulk of workers, over 113,000, are in the Other Retail and Restaurants and Bars sectors. Overall, the six most impacted sectors account for just over 17% of all payroll employment in Puerto Rico. The graph below breaks down the total share by affected sector. In theory, these should be the sectors to benefit the most from the PPP in Puerto Rico.

We will be conducting further analyses and sharing these in the coming days. We must note that the QCEW data analyzed does not include all workers, just those covered by unemployment insurance (UI). This leaves out most of the self-employed and other minor categories. Nonetheless, employment covered by UI represents about 89% of wage and salary employment in Puerto Rico.

The PPP in Puerto Rico

At first glance it would appear the implementation of the PPP in Puerto Rico was a success: according to the SBA local lenders approved 2,856 loans in an aggregate amount of $658,573,638. The average loan amount was $230,593, some $24,572 higher, or 12%, than the PPP average loan amount of $206,021.

However, when we analyze Puerto Rico relative to other states, it appears the performance of Puerto Rican lenders was deficient. In 2019, the relevant year for analysis, there were 44,422 businesses in Puerto Rico with less than 500 employees and approximately 120,000 persons who were self-employed. Puerto Rico today has approximately 1% of the population of the United States, yet it received only 0.17% of all loans by count and 0.19% by amount under the PPP. And, as shown in the graph above, it ranked 52 out of 56 jurisdictions (the 50 states, DC and the five territories) in total amount lent.

Furthermore small businesses in 21 jurisdictions with less population than Puerto Rico—Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming—received a larger aggregate amount of PPP loans than Puerto Rico.

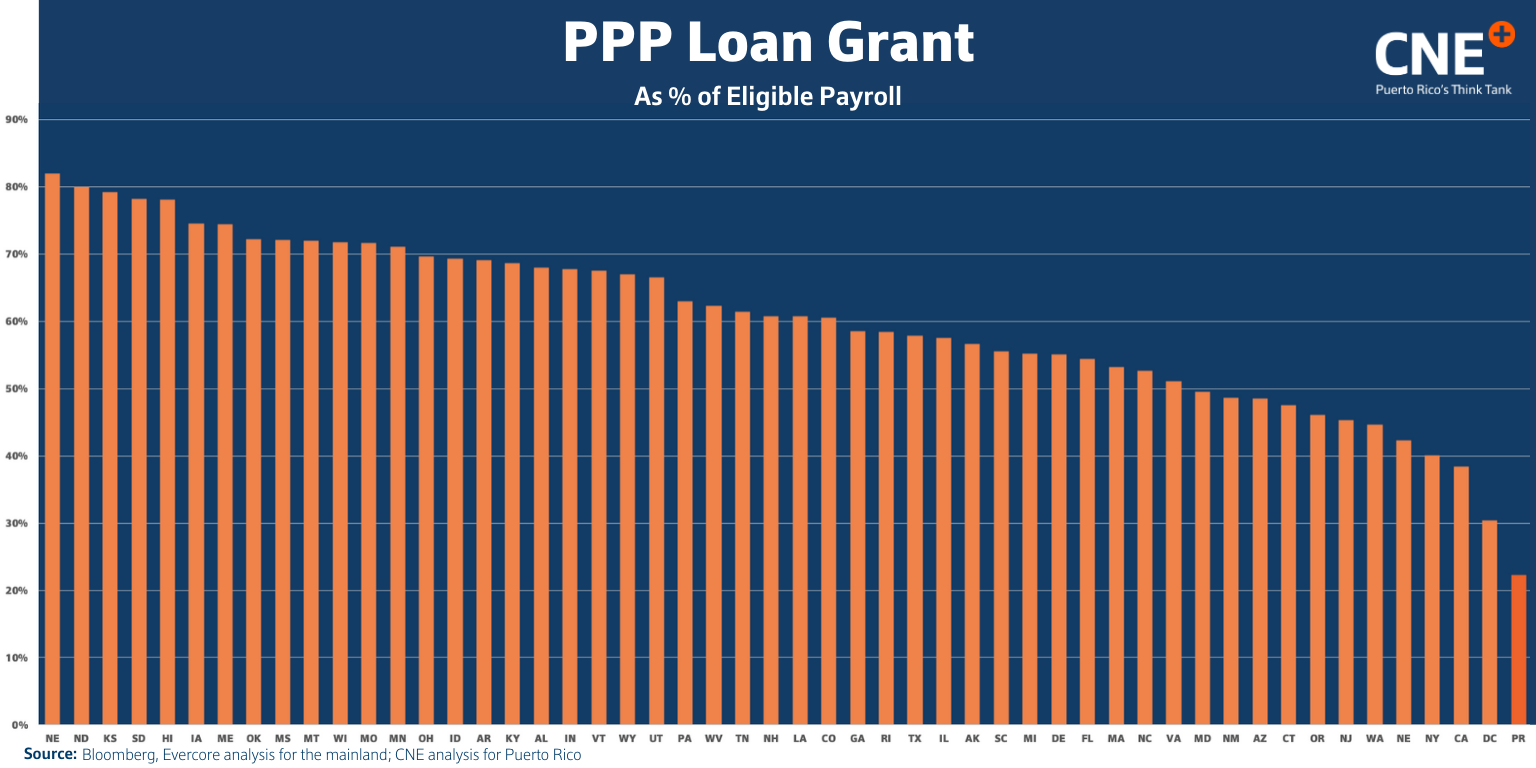

We can also analyze the performance of local lenders using a different metric. On April 17, Bloomberg published a story by Zachary Mider and Cedric Sam highlighting an analysis of the PPP done by Mr. Ernie Tedeschi, an analyst at Evercore, a boutique investment bank. Mr. Tedeschi calculated the amount of PPP loans approved as a percentage of eligible payroll in order to compare states in relative terms. He calculated the average monthly payroll amount paid by firms with less than 500 employees and multiplied that number by 2.5, the product of which yields the maximum PPP amount allowable under the rules.

We replicated the analysis for Puerto Rico using data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages carried out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Labor Department. According to our analysis, the eligible payroll amount for Puerto Rico is approximately $2 billion, while the total amount lent in Puerto Rico, as we stated before, was $658 million. Thus, the aggregate loan amount as a percentage of eligible payroll for Puerto Rico is 33%.

As shown in the graph below, that puts Puerto Rico second to last behind the District Columbia. This means that qualified employers in Puerto Rico received PPP loans in an aggregate amount to cover only one-third of all eligible payroll expenses, while firms in Nebraska, for example, received enough cash to cover 82% of the state’s eligible payroll. Given those statistics it is hard not conclude that someone dropped the ball in Puerto Rico.

These findings highlight the uneven distribution of PPP loans throughout the fifty states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Mr. Tedeschi offered some theories to explain those disparities:

“One was that regions hit harder by the virus, or that had the earliest lockdowns, may have had more trouble getting lending started. Another was that more businesses in hard-hit states may not have applied because the program isn’t enough to make a difference for them. Tedeschi also floated the possibility that businesses in some states had better pre-existing relationships with community banks that were able to get applications submitted quickly.”

Clearly further research is necessary to determine the causes of the highly uneven distribution of PPP loans. However, the authors of the Bloomberg story also noted an interesting pattern in the data: 8 of the top 10 states that received the largest amount of PPP loans as a percentage of eligible payroll are reliably Republican states: Nebraska, North Dakota, Kansas, South Dakota, Iowa, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Montana. Now, it is not possible to conclude, with the data available, that there was a political bias in the approval of PPP loans. But the pattern surely deserves further investigation and analysis.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In the case of Puerto Rico, it is fairly obvious we failed to take advantage of an important federal relief program to the full extent possible. The question is why. To answer that question we will need more information: how many firms applied for loans; how many applications were denied; what is the distribution of the firms that were rejected by number of employees and revenues; what is the distribution of the 2,856 loans that were approved, by count, loan amount and economic sector; and how many of the beneficiaries had pre-existing lending relationships with the lender of the PPP loan.

Until then we just have to conclude the local financial sector failed miserably in Puerto Rico’s hour of need. Keep in mind that local lenders stand to make up to $33 million in fees essentially for conducting a minimal credit analysis, pushing papers, and making a risk-free loan. Which is highly ironic, given that the prevailing discourse in Puerto Rico is that government can’t get anything right. This time around it was a key part of the private sector that failed thousands of small businesses.

Given all of the above we make the following recommendations:

- Congress should extend funding for the PPP, perhaps by an additional $500 billion as has been suggested by Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta;

- the PPP should be modified to target it better to needy communities, perhaps by setting aside a funding stream for minority-owned businesses;

- the delivery platform needs more guardrails to discourage lender shenanigans to favor their preferred clients;

- Congress should require more transparency from lenders as they receive and process applications; and

- Congress should subpoena documents from SBA and lenders and eventually hold oversight hearings, specifically the House Committee on Small Business Chaired by Rep. Nydia Velazquez; the House Committee on Financial Services, chaired by Rep. Maxine Waters; and the House Committee on Natural Resources, chaired by Rep. Raul Grijalva, in the case of Puerto Rico.

Quote of the Day

“A bank is a place that will lend you money if you can prove that you don’t need it.”

– Bob Hope

This is the end of today’s Special Edition briefing.

Stay safe and well informed!