Spain: The Deadly Cost of Austerity and Poor Governance

Published on October 22, 2020 / Leer en español

As COVID-19 cases surge again in Europe and key cities like Paris, Berlin and Barcelona take extraordinary measures to curtail the expansion of the virus, Spain’s management of the pandemic has come again under scrutiny. The prestigious international medical journal The Lancet has published yet another stark evaluation of the country’s response to the pandemic, stating – in a sobering warning to all countries struggling to contain the disease – that “Spain’s COVID-19 crisis has magnified weaknesses in some parts of the health system and revealed complexities in the politics that shape the country”.

The article COVID 19 in Spain: A Predictable Storm? identifies several factors that have laid bare the frailties of the Spanish health system and the reasons for its seeming incapacity to deploy a robust response: weak epidemiological surveillance structures, low capacity for PCR testing, scarcity of both personal and critical care equipment, a lack of preparedness in nursing homes, and conspicuous inequalities in care among social groups. All these weaknesses, the journal notes, are the result of a decade of austerity that has notably reduced the system’s ability to adequately manage the pandemic.

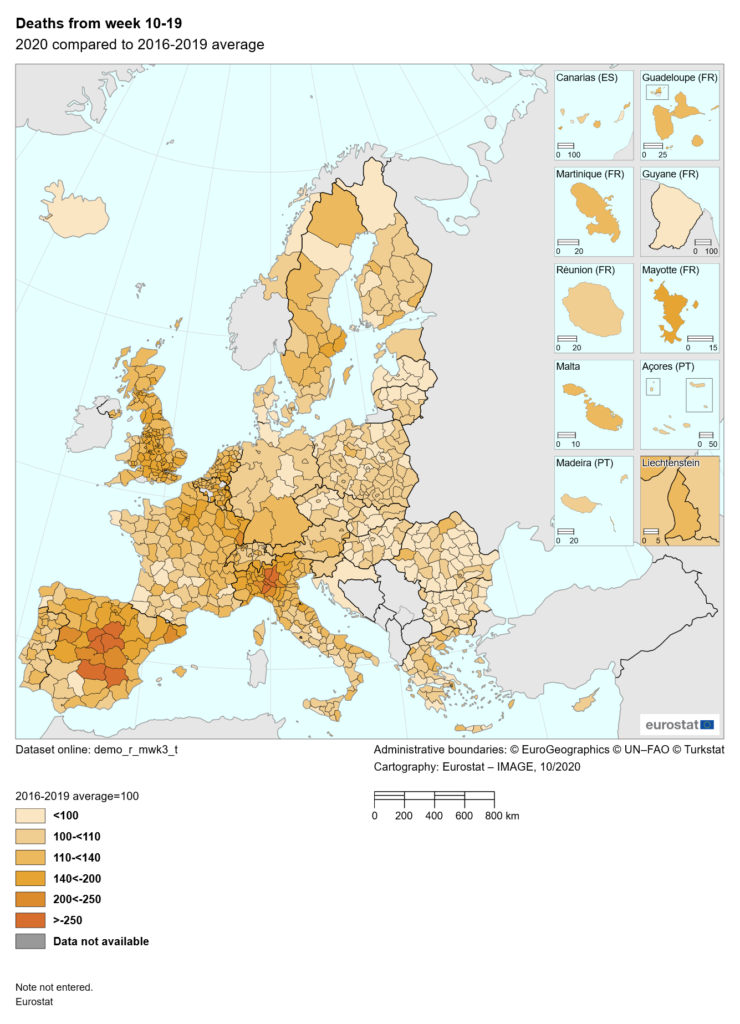

Between March and June 2020, Spain registered the largest increase in deaths (excess deaths) of all Europe. Some regions of the country have been among the hardest hit by the pandemia. Excess deaths are tabulated comparing all deaths registered during the pandemia with those registered during the same period in past years.

Map: Eurostat, “Deaths in weeks 10 to 19, 2020 compared to 2016-2019 average”

According to the investigative journal Newtral, public expense in health stagnated in Spain since 2009, a result of years of budget adjustments brought about by the 2008 financial crisis. This, according to The Lancet, has rendered the Spanish health system “understaffed, under-resourced and under strain”, that is, perilously unprepared for the emergency. Spain currently has one of the lowest nurse-per-inhabitant ratios in the European Union: 5.9 nurses vs. the European average of 9.3 per 1,000 inhabitants. Staffing has increasingly relied on short-term contracts that have all but rendered health and medical professionals in a precarious position. Data systems – fragmented and lacking key demographic variables, according to The Lancet – have also been insufficient to trace the dynamics of the pandemic. And the test-trace-isolate strategy (the cornerstone of any epidemiological response) has remained weak.

On top of all this, the article notes, the government’s response has been seemingly inadequate, plagued by slow decision-making processes, low reliance on scientific advice, and poor coordination among central and regional authorities. The battle between the Community of Madrid (controlled by the conservative Partido Popular/PP) and the central government (controlled by the Partido Socialista/PSOE) over mobility and economic restrictions in the capital city has been strident and bitter, with El País recently chastising both over the deadly and acrimonious political tug-of-war and madrileños anxiously scrambling to decode the changing rules.

Until now Spain had been rightly proud of its national health system. Publicly funded, it guarantees universal coverage to all Spanish nationals and coexists with a complementary private health network. As recently as 2018 a Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) Index published by The Lancet had found the Spanish health system to be among the top of those evaluated, ranking #19 after Germany’s ranking of #18. Fifteen of the top 20 HAQs identified by the study were in European countries, with the USA ranking a distant #39. According to the Spanish Ministry of Health, the country invests 9% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in health services, with the public system accounting for 70% of expenses with €74,000 million euros per year (about $86,700 million dollars). COVID-19 seems, however, to have become a bleak indicator of the need for future reform.