Introduction

It has been about three years and eight months since Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. It is as good a time as any, to take stock of the post-storm reconstruction and recovery process as we approach the beginning of yet another hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean.

According to official estimates, Hurricane Maria caused approximately 3,000 deaths and about $90 billion in damages. The ineffective initial response from both the Puerto Rico and federal governments, exposed long-existing economic, political, and social inequalities, as well as Puerto Rico’s subordinated standing in the United States’ political system. Eventually, Congress approved part of the funding required for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction, but in many cases with highly prescriptive conditions and requirements that have unduly delayed and burdened the reconstruction process.

The Federal Appropriations Process and Disaster Assistance

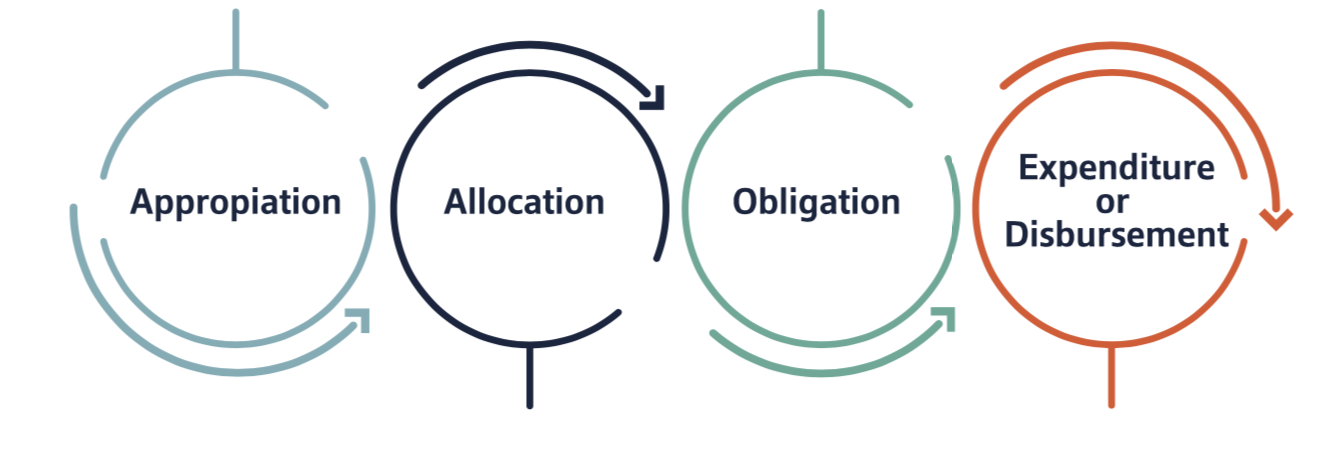

Congress makes decisions about spending specific funds through a complicated “appropriations process.” The key concepts to understand in this process are:

- First, Congressional committees of jurisdiction draft and negotiate appropriation bills, which provide the legal authority to obligate and spend money from the U.S. Treasury.

- Second, funds are then allocated, sometimes by legislation, but most often by the Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”), which authorizes the transfer of funds from a global appropriation account to fund a specific program run by a government agency.

- Third, funds are then obligated, this occurs when a government agency makes a definite commitment that generates a legal liability of the federal government for the payment of goods and/or services.

- Finally, an expenditure or outlay occurs when a specific amount is paid by a federal agency. In plain language, this is when the U.S. Treasury writes a check to pay for the program

In graphic form, this budgetary process flows roughly as follows:

Federal Disaster Funding Update

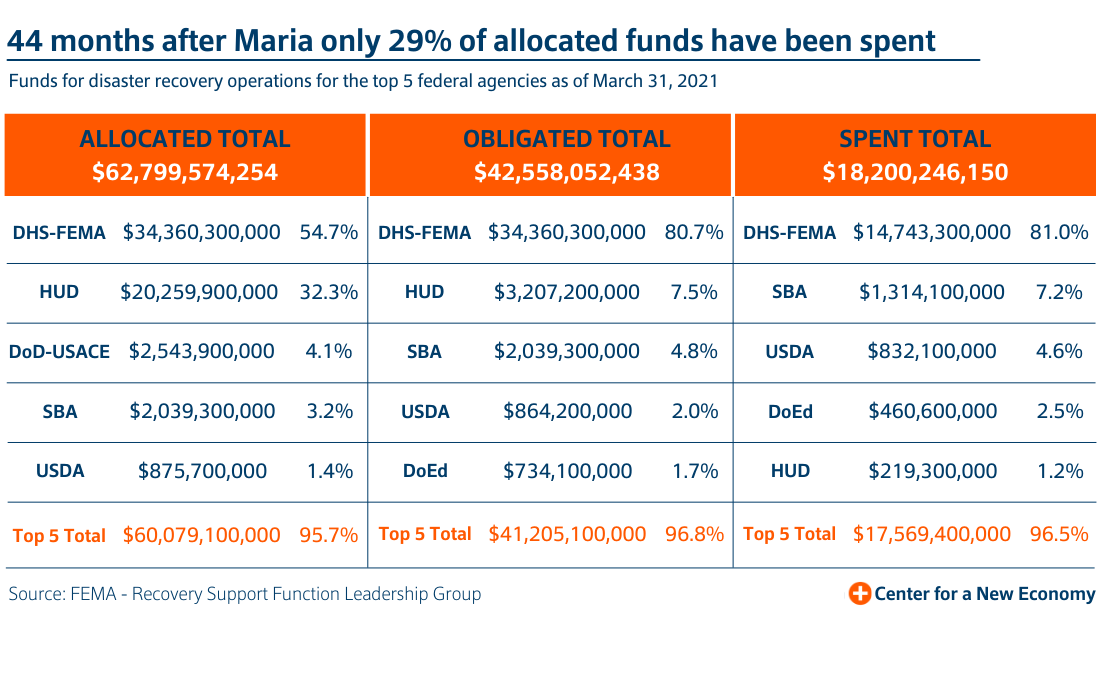

A total of seventeen federal agencies have allocated funds for disaster recovery operations in Puerto Rico since 2017. As shown in the table below, as of March 31, 2021, a total of approximately $63 billion has been allocated for disaster relief and reconstruction activities in Puerto Rico. About 90% of those funds have been allocated to three agencies: FEMA, HUD, and USACE.

Of the approximately $63 billion that have been allocated, about $43 billion, or 68%, have been obligated, mostly by FEMA, HUD, and the SBA.

Finally, of the $43 billion that have been obligated, about $18 billion, or 42%, has been spent or outlayed, mostly by FEMA, SBA, and USDA. Notice, however, that 44 months after Hurricane Maria, total outlays amount to only 29% of the total amount allocated by Congress.

Management of Disaster Assistance Funds

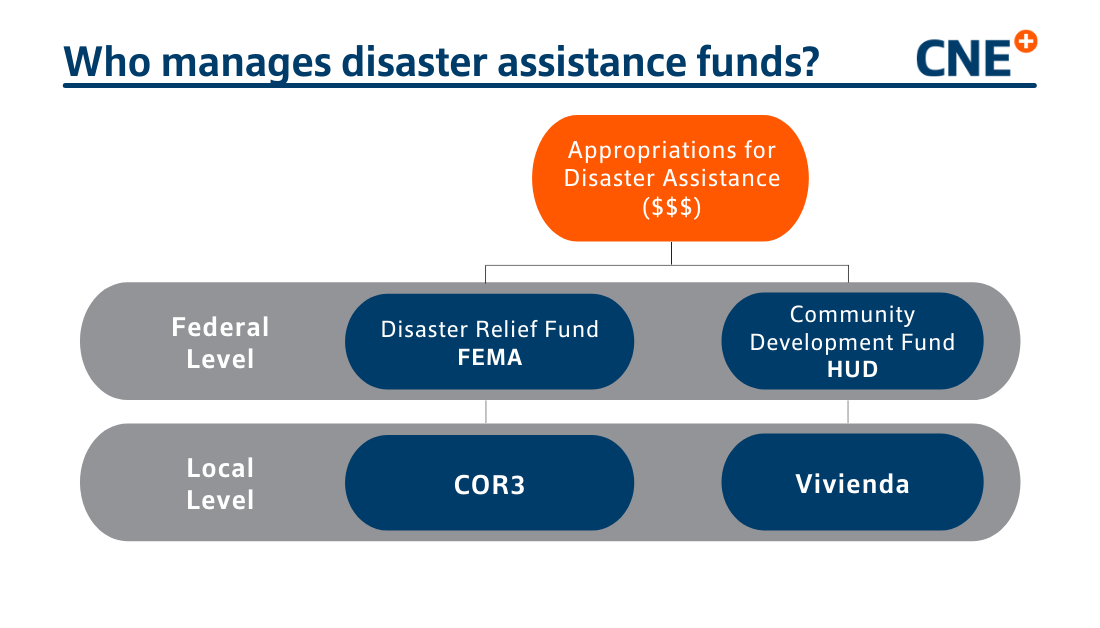

In the case of appropriations for disaster assistance, the federal government operates through two principal “master accounts”:

- The Disaster Relief Fund managed by FEMA; and

- The Community Development Fund, managed by HUD, which finances the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (“CDBG-DR”)

FEMA works with the Puerto Rico Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction, and Resiliency (“COR3”) to manage its assistance programs in the island, while HUD works with the Puerto Rico Housing Department (“Vivienda”) to administer CDBG-DR programs in Puerto Rico.

FEMA

FEMA provides three major categories of assistance, subject to the requirements of the Stafford Act:

- Public Assistance (PA) provides grants to tribal, state, and local governments, and certain private nonprofit organizations for emergency protective measures, debris removal operations, and repair or replacement of damaged public infrastructure.

- Individual Assistance (IA) provides direct aid to affected individuals and households, and can take the form of housing assistance, other needs assistance, crisis counseling, case management services, legal assistance, and disaster unemployment insurance.

- Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) funds mitigation and resiliency projects and programs, typically across the entire state.

The slow disbursement of funds for permanent work public assistance projects has been the main focus of contention between FEMA and COR3 for three years now. Permanent work categories under the Public Assistance Program include:

- Restoration of roads/bridges (Category C);

- Water control facilities (Category D);

- Buildings/equipment (Category E);

- Utilities (Category F); and

- Parks, recreational and other facilities (Category G)

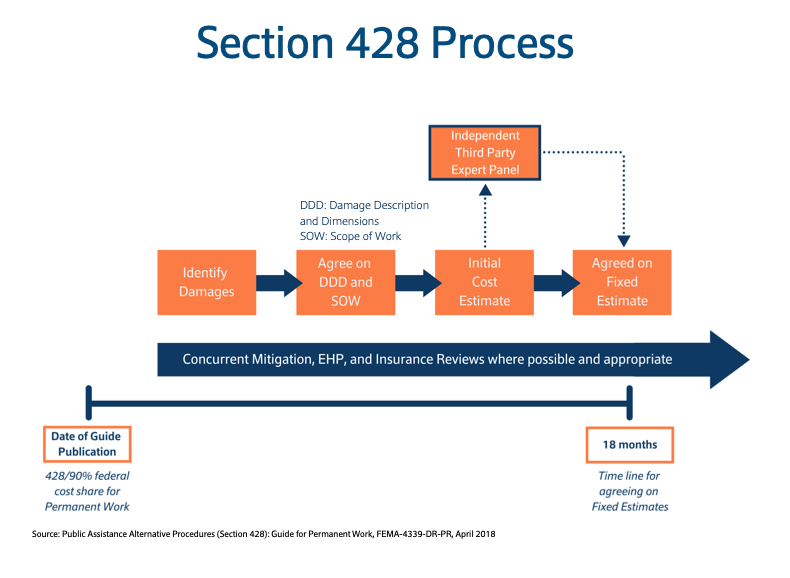

The delay in disbursing these funds can be partially attributed to the decision by FEMA and the government of Puerto Rico to use an alternative process for the disbursement of these funds, following Section 428 of the Stafford Act. According to a report published in September of 2018 by the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”), New York and New Jersey used this alternative process to finance a small percentage of the permanent work in those states after Hurricane Sandy, but no jurisdiction has used these alternative procedures to finance 100% of the permanent work under FEMA’s public assistance program. (See GAO Report 18-472.)

According to the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico (“FOMB”), the “428 Program makes possible the consolidation of multiple projects into a single fixed-cost sub-grant, which allows greater flexibility rebuilding or restoring disaster damages. The 428 Program goals include: (1) to reduce costs to the federal government stemming from public assistance, (2) to increase flexibility administering that assistance, (3) to expedite aid to the state, tribal or local government or owner of a non-profit, and (4) to provide financial incentives and disincentives for timely and cost-effective Public Assistance projects.” (Disclosure Statement for the Third Amended Title III Joint Plan of Adjustment of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, et al., May 11, 2021, p. 222).

In practice, however, the Section 428 process has turned out to be unduly bureaucratic, drawn-out, and, in our view, has failed to meet its programmatic objectives. This process for approving permanent work projects under Section 428 was supposed to take 18 months from the date of publication of the guidelines for these projects, in April of 2018, a deadline that has been extended several times, most recently to December 31, 2021.

The slow pace of these approvals has been due, in part, to the fact that both FEMA and Puerto Rico had very little experience managing projects under Section 428. Furthermore, as can be seen in the chart below, the process is not as streamlined as might be at first thought:

- First, the sites or infrastructure elements that were damaged and that qualify for the financing of permanent work under the public assistance program are identified.

- Second, a description of the extent and dimensions of the damage is prepared.

- Third, the “scope of work” necessary to repair the damage is analyzed and agreed upon with FEMA.

- Fourth, an initial estimate of costs is prepared. In general terms, if the project has a cost estimated to be more than $5 million, or if FEMA and the government of Puerto Rico do not agree as to the initial cost estimate, the initial estimate is submitted to an independent panel of experts for review and validation.

- Fifth, a final fixed cost estimate as endorsed by the panel is prepared.

- Sixth, a project worksheet for the work to be carried out is prepared. The proposed project is then reviewed and, eventually, approved by FEMA.

- Once the project is approved, the funds for it are legally obligated or committed. The COR3 then is in charge of overseeing the progress of the work undertaken and reimbursing the funds to the agency or company contracted to carry it out.

Perhaps more important, the version of the alternative procedures approved for Puerto Rico does not allow FEMA to accept estimates made by the applicant. Instead, the estimates must be done by professionals licensed by FEMA. This, too, is different from FEMA’s treatment of the states. (See “Public Assistance Alternative Procedures [Section 428], Guides for Permanent Work, FEMA-4339-DR-PR. Appendix A, April 2018.)

Notwithstanding all of the above, some progress has been made over the last three years. According to data from the FOMB, as of February 2, 2021, some 8,033 projects have been obligated under the Public Assistance program, totaling $23.6 billion. Currently, the deadline for applicants to reach a consensus on Section 428 projects is December 31, 2021.

HUD & CDBG-DR Funds

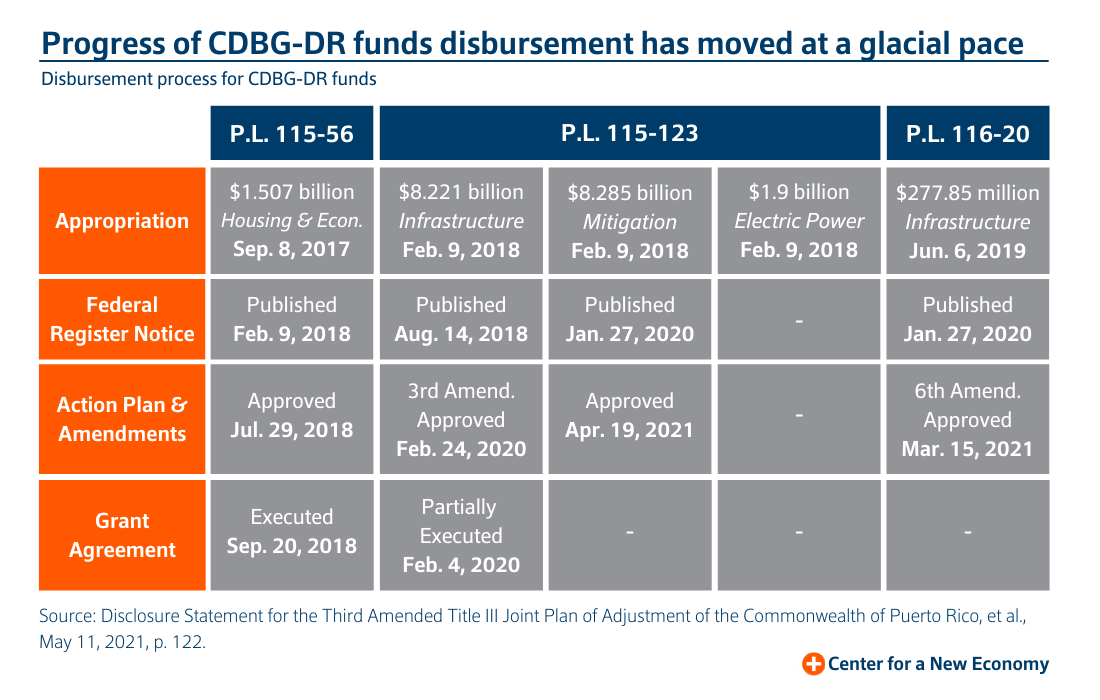

Between September 2017 and June 2019, Congress appropriated approximately $20.3 billion in Community Development Block Grant (“CDBG-DR”) funds for disaster reconstruction and mitigation activities related to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico through three supplemental appropriation acts:

- L. 115-56: $1,507,179,000 for unmet needs (a significant portion of these funds was used for the Home Repair, Reconstruction, or Relocation Program, also known as R3);

- L. 115-123: $10,153,130,000 for unmet needs (including $1.9 billion to enhance and modernize the electric grid) and $8,285,284,000 for mitigation activities; and

- L. 116-20: $304,000,000 for unmet needs.

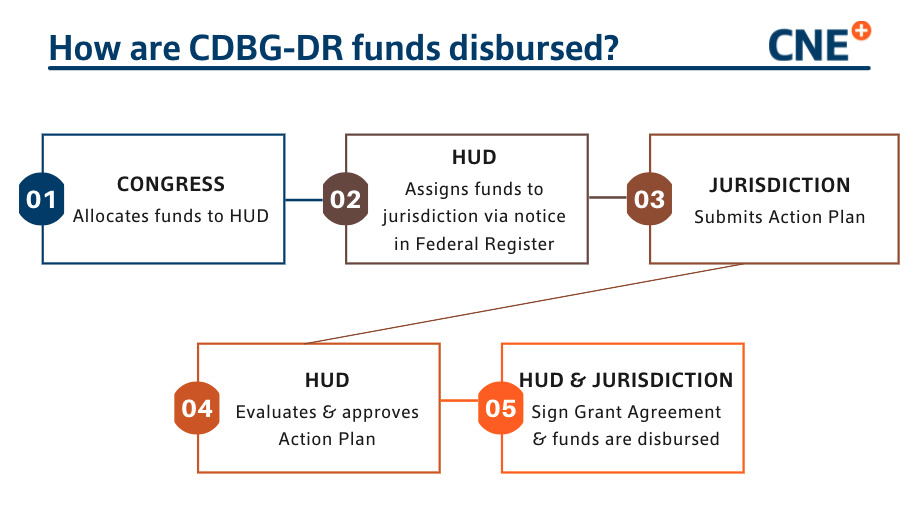

The usual process for disbursing these funds is somewhat cumbersome. As shown in the chart above, after Congress appropriates the money, HUD has to publish a notification in the Federal Register. The intended beneficiary then proceeds to draft an Action Plan for the use of the funds, in accordance with the published regulations. If and when the Action Plan is approved by HUD, then the parties need to execute a Grant Agreement to allow the expenditure of funds in accordance with the terms of the Action Plan.

The process for disbursing the first tranche of CDBG-DR funds, $1.5 billion from P. L. 115-56, moved relatively quickly, taking about a year from appropriation to the execution of the Grant Agreement.

However, the process for releasing the next tranche of funding, some $8.21 billion appropriated pursuant to P. L. 115–123, was unduly drawn out. It took approximately two years from appropriation to the execution of the Grant Agreement on February 4, 2020. Furthermore, this Grant Agreement included a series of unprecedented conditions that Puerto Rico had to fulfill before obligating those funds, which were imposed on top of the already burdensome requirements that both a HUD financial monitor and the FOMB approve and review the use of CDBG-DR funds in Puerto Rico.

The process for approving the use of the $8.28 billion appropriated for mitigation activities, which was approved by Congress on February 9, 2018, was even more tortuous. HUD did not publish the required notice in the Federal Register until January 27, 2020 and the Action Plan for the use of those funds was not approved until April 19, 2021, more than three years after Congress had appropriated the funds. The Grant Agreement for using these funds has not been executed as of this writing.

Furthermore, the disbursement/drawdown of the $8.28 billion assigned by P. L. 115-123 for mitigation projects and the $304 million for unmet needs assigned by P. L. 116-20 is contingent on Puerto Rico reaching an agreement with FEMA, within the calendar established by FEMA, on all the fixed-cost estimates for permanent work projects pursuant to Section 428. (See P. L. 116-20, Section 1102.)

We do not know why Congress decided to impose this additional restriction on the disbursement of these funds, but it clearly puts Puerto Rico in a difficult situation. Given that the period for the approval of 428 projects has already been extended several times, it should not be surprising that the disbursement of these tranches of CDBG-DR funding has been delayed. To the best of our knowledge, this condition has been imposed only on Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Finally, there has been absolutely no action regarding the $1.9 billion specifically appropriated by Congress for modernizing and rebuilding Puerto Rico’s electric system. These funds were specifically allocated by Congress in P. L. 115–123, which, as we have stated, was approved by Congress on February 9, 2018. This inexplicable delay is unacceptable.

In sum, according to the Disclosure Statement recently filed by the FOMB, “as of December 31, 2020, a total of $9.7 billion has been made available to Puerto Rico of the over $20 billion appropriated to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development through Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery, (“CDBG-DR”)”. While it is true that the Biden Administration has been more diligent in moving the bureaucratic process that regulates these funds, it is not clear to us what the FOMB means when it states that “$9.7 billion has been made available to Puerto Rico”, as this is not a defined federal budgetary term.

Nonetheless, the pace of disbursing and using these funds has been extremely slow as the FOMB itself admits. According to the Board, the largest of the various CDBG-DR programs “is the housing reconstruction program which is budgeted for $1.1 billion of which approximately $78 million has been spent as of December 31, 2020 according to PRDOH’s December 2020 Quarterly Report.” (Disclosure Statement, p. 121).

Finally, Funding is Important, but…

The reconstruction of Puerto Rico and the economic recovery and growth tied to that reconstruction have been slower than initially anticipated. This delay is mostly attributable to the federal bureaucracy, the use of an alternative process that so far has not functioned as expected, and the discriminatory, burdensome, and unreasonable conditions imposed by Congress, FEMA, and HUD on Puerto Rico.

However, obligating and spending the federal funding assigned for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction and recovery is only one part of that process. The sequence of events we call “Hurricane Maria”, and their consequences, have their roots in multiple decisions that were made decades ago. For example, Why do we have high-voltage power transmission lines that cross the island from south to north, over the central mountain range?; Why were Levittown and Puerto Nuevo built where they were built?; Why did our legislators allow owners and operators of critical infrastructure to have little or no electricity back-up?

Seen from this perspective, the damage caused by Hurricane Maria cannot be attributed solely, or even primarily, to the meteorological event. Indeed, scholars increasingly assert that “there is no such thing as a natural disaster, because who is in harm’s way is the product of political decisions and social arrangements, rather than the inevitable order of things…Vulnerability is socially constructed.” (Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1915-2015, p. 13).

The question for Puerto Rico is, then, are we going to build back in a way that replicates those vulnerabilities? The answer to that question, in turn, raises other rather problematic political questions. Who and how do we decide to spend this federal windfall? What do we preserve, what do we leave to waste, and who decides? Who is deemed “worthy” of help, why, what kind, and from whom? For instance, Which coastal community gets a seawall and which community is relocated to a “safer area”?; Whose neighborhood gets razed to the ground, displaced, or gentrified in the name of “redevelopment”?; Where do we build new public schools, hospitals, and electric, water, and telecommunications infrastructure, and who decides?

These are only some of the thorny questions we will face as we move forward with the reconstruction of the island. It is good to keep them in mind because they remind us that these are political decisions in no way preordained or inevitable in the wake of Hurricane Maria. As Horowitz reminds us: “The etymology of the word disaster refers to stars out of alignment; but if the changes in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina seemed to some to proceed with the force of destiny, it is well to remember as Shakespeare cautioned, ‘The fault…is not in our stars, But in ourselves, that we are underlings’.” (Horowitz, Katrina, p. 5).

In the end, then, the shape of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria will depend to a large extent on how we address long-standing issues of class, race, segregation, poverty, inequality, and political power that we have ignored for far too long.