UPR’s role in economic development in Puerto Rico: Research and Development

Published on August 16, 2021 / Leer en español

Given that it provides higher education for the largest share of total students enrolled, the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) is an essential institution in ensuring social mobility in Puerto Rico. Likewise, it is a central institution in furthering the arts and humanities, which are essential disciplines for producing critical thinkers, sensible human beings, and fostering cultural exchanges between Puerto Rico and the rest of the world. In this section, however, we will focus on examining the UPR’s role in research and development (R&D) in the archipelago, a basic component of any industrial and economic development policy.

Puerto Rico R&D in numbers

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), Puerto Rico’s output in R&D in 2017 totaled 0.54% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Using Gross National Product (GNP), this measure increases to 0.81%. Regardless of the measure used, Puerto Rico’s output of R&D as a percentage of total economic output is far below that of the United States (2.79% of GDP in 2017), let alone the leading nations in the world in this regard, South Korea (4.3% of GDP) and Japan (3.2% of GDP). Higher education institutions in Puerto Rico represent around a third of total R&D output (businesses and private enterprises almost comprise the remaining two thirds). Therefore, if Puerto Rico is to become competitive in R&D, it must substantially increase its R&D output by higher education institutions.

Examining the UPR’s role in R&D in Puerto Rico requires breaking down how it performs in comparison to private higher education institutions. Data from the Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey, compiled by the National Science Foundation (NSF), show that, between 2010 and 2019, total higher education spending in R&D peaked at $162 million in 2011 and had been in decline until 2019, when it reached an uptick of $123 million (Figure 1). Regardless of total spending, R&D output by UPR comprises around 80% of total higher education spending in R&D in Puerto Rico. The data also show that, even when UPR campuses reduce their R&D output, private institutions do not reflect an increase in their total R&D output. Furthermore, between 2010 and 2019, campuses from the Ana G. Méndez University System and the Universidad Central del Caribe reduced their total R&D output by almost half. In this regard, only the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico and the Ponce Health Sciences University saw increased R&D output in that same period among private institutions, with the latter comprising more than half of total R&D output by private institutions in 2019.

Figure 1: Yearly research spending and share of total spending by higher education institutions in Puerto Rico. Source: FY 2019 HERD Survey, NSF

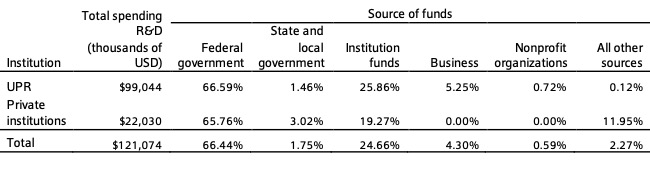

Breaking down spending in R&D in FY2019 by source of funds also reveals additional important insights (Table 1). Although funding from the federal government totals around two thirds of total funds for both UPR campuses and private institutions, more than a quarter of R&D spending in the UPR comes from its own institutional funds. This includes funding used for cost-sharing, seed funding, and administrative costs, among other expenditures. UPR institutional funds represent more than a fifth of total higher education R&D spending in Puerto Rico (around $25 million, close to half the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico’s (FOMB) budget).

Table 1: Share of total higher education spending in R&D in Puerto Rico by institution and source of funds for FY 2019. Source: FY 2019 Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey, NSF

It is also worth considering that UPR houses research centers and facilities that are unique among higher education institutions in Puerto Rico. Many of these not only provide research opportunities for UPR faculty, but also for faculty in private institutions. Some highlights include:

- The Dr. Federico Trilla Hospital in Carolina

- The many Agricultural Extension Service centers administered by UPR Mayagüez

- The Puerto Rico Seismic Network

- The Center for Hemispherical Cooperation in Research and Education and Engineering and Applied Science (CoHemis)

- The Caribbean Regional Integrated Ocean Observation System (CARICOOS)

- The Coastal Research and Planning Institute of Puerto Rico

- The Center for Innovation, Research, and Education in Environmental Nanotechnology

- The Atmospheric Stations administered by UPR Río Piedras

- The Resource Center for Science and Engineering

- The Luquillo Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER)

- The Puerto Rico Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR)

- The Caribbean Primate Research Center

- The NASA Puerto Rico Space Grant Consortium

Possible consequences of proposed budget cuts by the FOMB

To remain competitive in R&D funding, universities in the U.S. offer competitive salaries and benefits to attract and retain researchers in the cutting edge of their respective disciplines. Universities must also have in place an administrative structure with highly skilled staff that can manage the rigorous administrative requirements set forth by federal and private funders to ensure efficiency, transparency, and proper oversight.

When interviewed by CNE colleague, Jennifer Wolff, Dr. Elvia Meléndez-Ackerman, Professor of Environmental Sciences at UPR Río Piedras, highlighted how past budget cuts have made research an increasingly precarized affair. The UPR already provides less than competitive salaries and benefits, causing research programs to lose key staff and hindering the recruitment of potential researchers. Budget cuts have also pushed university departments to increase the undergraduate teaching load to their faculty, while decreasing both research and graduate-level teaching loads. In addition, administrative consolidations have reduced the availability of experienced and dedicated administrative staff in managing research-related endeavors.

Furthermore, hiring freezes for both faculty and administrative staff are likely already overly burdensome to ensure competitiveness in ensuring external funding and sustaining an administrative structure that can comply with regulatory requirements.

Our analysis of R&D activity in Puerto Rico shows that private institutions have been unable to increase their R&D output to a degree that can compensate for reduced R&D activity by UPR campuses, and that UPR institutional funds are an essential component of total R&D activity in the archipelago. Thus, the proposed budget cuts by the FOMB will very likely reduce total R&D output in Puerto Rico, render the archipelago increasingly less competitive in R&D, and doom the possibility of success of any serious industrial and economic development policy focused on fostering high added-value activities.