Written Testimony Submitted to the United States Commission on Civil Rights

Published on December 10, 2021

Table of Contents

Introduction

Good morning distinguished members of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, fellow witnesses, and all those who are following these proceedings. We have received your letter of October 27, 2021 inviting us to testify today about the U.S. federal government response to Hurricane Maria. We thank you for the opportunity to participate in this important public debate. We at the Center for a New Economy believe it is important to bear witness about the way Hurricane Maria’s victims were (mis)treated by some agencies of the federal government. It is a moral obligation we owe to those who suffered in the immediate aftermath of the storms, to those who are still living with their consequences, and to people who, unfortunately, will become victims of natural disasters in the future.

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane María wreaked havoc on Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands by unleashing the power of nature with a fury unseen in these parts in almost a century. According to data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”), within hours of Hurricane María’s landfall in Puerto Rico, 100 percent of the clients of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (“PREPA”) were without electric power service; 80 percent of all PREPA infrastructure was destroyed; 80 percent of the clients of the Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority (“PRASA”) were without water service; between 80 and 85 percent of communication towers were not operational; hundreds of miles of roads were closed off by landslides and several dozen bridges collapsed; maritime ports and airports were closed, and remained so for at least five days; and satellite phones were not working at all.[1]

In addition, 92% of hospitals were severely impacted; between 23 and 31 million trees were destroyed or damaged; approximately 527,000 households reported some kind of damage; thousands of small and medium business were closed for months and many went out of business; several hotels and resorts suffered serious damage; and economic activity, as measured by the government’s Economic Activity Index, declined by approximately 12% over the three months immediately following the hurricane.[2] According to estimates made by Moody’s Analytics, the decrease in real GDP could have been as deep as 15% during the last calendar quarter of 2017, while approximately 35,000 jobs were lost. Furthermore, Moody’s estimates that Hurricane María caused about $80 billion in damages to the island’s already withered capital stock and at least $25 billion in lost output, which has adversely affected business and household balance sheets.[3]

FEMA, using a model designed by NOAA, estimated total damages add up to approximately $90 billion in Puerto Rico and the USVI, while the government of Puerto Rico estimated total damages at around $139 billion.[4] The ineffective initial response from both the Puerto Rico and federal governments, exposed long-existing economic, political, and social inequalities, as well as Puerto Rico’s subordinated standing in the United States’ political system. Eventually, Congress approved part of the funding required for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction, but in many cases with highly prescriptive conditions and requirements that have unduly delayed and burdened the reconstruction process.

In the case of appropriations for disaster assistance for Puerto Rico, the federal government operates through two principal “master accounts” and four main agencies: the Disaster Relief Fund managed by FEMA, which works with the Puerto Rico Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction, and Resiliency (“COR3”) to manage its assistance programs in the island; and the Community Development Fund, managed by HUD, which finances the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (“CDBG-DR”) program and works with the Puerto Rico Department of Housing (“PRDOH”) to administer CDBG-DR programs in Puerto Rico.

FEMA

In general, FEMA spending on disaster assistance can be divided into (1) assistance for emergency work, which covers both individual and public assistance; and (2) spending on permanent work, which is usually earmarked for public assistance for both reconstruction of infrastructure and hazard mitigation projects.

The initial disbursement of emergency assistance for individuals after Hurricane Maria was marred by bureaucratic bungling and mismanagement. For example, a year after Hurricane Maria, the portion of total funds obligated for individual assistance programs for Hurricane María’s disaster victims (17%) was significantly lower than the portion obligated for individual assistance for the victims of Hurricane Harvey (47%) or Hurricane Irma (32%). The relatively low share of obligations is partly explained by FEMA insistence that potential beneficiaries produce “clear” title to the property they inhabited, even though its regulations did not set forth that requirement. As one or more of my fellow panelists will testify, this situation resulted in the unjustified denial by FEMA of most applications for individual assistance.

It is however in the area of spending for permanent public works where FEMA has consistently underperformed. According to the GAO this lag is largely due to the requirement that FEMA and the government of Puerto Rico use alternative procedures under Section 428 of the Stafford Act for all large Public Assistance permanent work projects, after an amendment to the presidential disaster declaration for Hurricane Maria, dated November 2, 2017, required that FEMA obligate all large project funding for Public Assistance permanent work through alternative procedures.[5] These alternative procedures:

…are designed to give jurisdictions more flexibility in determining how, where, and what to rebuild, particularly after incurring significant damage. Applicants may choose to combine multiple critical facilities and rebuild them in a manner that makes them less likely to incur future disaster damages. In 2013 FEMA began a pilot program to utilize the alternative procedures for debris removal and permanent work projects in the recovery from Hurricane Sandy in New York and New Jersey, as of April 2018, FEMA reported that 29 percent of New York’s permanent work projects are under the alternate procedures—approximately $8.6 billion. However, no state or territory has used alternative procedures for 100 percent of their permanent work projects. According to Puerto Rico’s Draft Recovery Plan issued in July 2018, the Commonwealth estimated costs for permanent work projects ranges from $26.7 billion to $37.4 billion.[6]

The requirement to use Section 428 alternative procedures for all large Public Assistance permanent work projects meant that the recovery process in Puerto Rico would flow according to a different schedule than that applicable to other jurisdictions and entailed both potential costs and benefits for the island:

According to FEMA officials, in the U.S. Virgin Islands and in the states, participation in the pilot program for permanent work alternative procedures will occur for select projects, by applicant request…They added that this approach will provide the flexibility Puerto Rico requires to achieve its post-disaster recovery goals while limiting risk to the federal government…However, it is unclear whether such flexibilities will eliminate other challenges associated with the PA program, such as reducing delays from challenges to eligibility determinations and supporting a timely recovery…although the front end of the PA alternative procedures pilot program may take longer than the standard PA procedures, once project formulation (including any identified hazard mitigation measures) and cost agreements are made, the entire sum of the agreed-upon funding level is obligated and made available to the recipient at a quicker rate due to the entire amount of the project being obligated from the outset. [Internal footnotes omitted.][7]

For Puerto Rico, the advantage of using these alternative procedures is that federal money will be obligated in full once there is agreement between the parties on the cost estimate for a particular project. The downside is that if the project is over-budget, it will be up to the government of Puerto Rico, which is undergoing a bankruptcy process, to fund the cost overrun. However, if there are any savings, the government of Puerto Rico could use those savings for other recovery-related activities. The advantage for the federal government is that it limits its exposure to the pre-agreed fixed cost estimate amount.

Given the magnitude of the damage caused by Hurricane Maria, it was foreseeable that the use of these alternative procedures would present implementation challenges and delays in developing fixed cost estimates. First, “since Puerto Rico is responsible for any costs that exceed fixed cost estimates for large permanent work projects under the alternative procedures, FEMA and Puerto Rico had to agree on guidance to develop the fixed cost estimates.” In February 2020, the GAO reported that FEMA had developed guidance for developing fixed cost estimates. However, it also found that the guidance did not meet all of the GAO’s best practices for estimating costs and the GAO recommended that FEMA revise the guidance to adhere more closely to best practices. As of January 2021, FEMA was working to address this recommendation. Second, the “use of alternative procedures can delay a project’s obligation because more time is required to develop a fixed estimate.”[8]

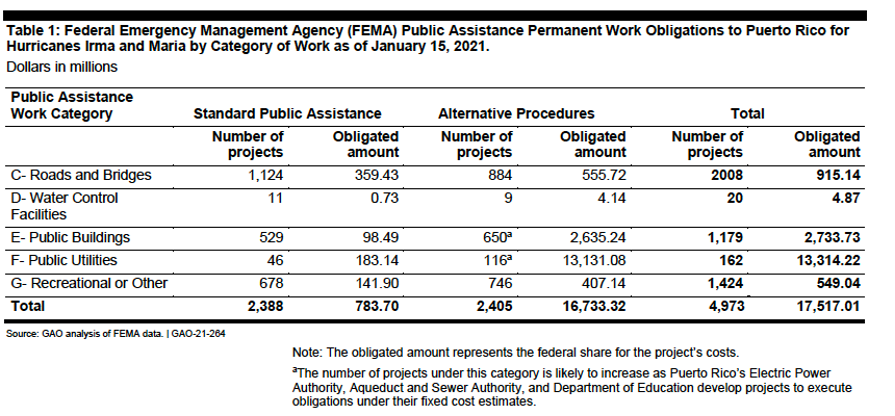

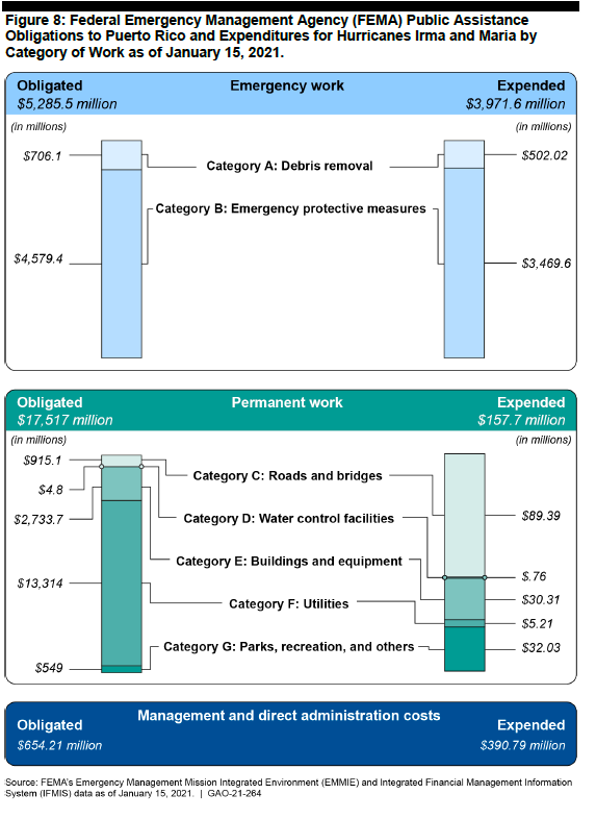

To be fair to FEMA, since 2019 it has implemented several changes to its Public Assistance Program in Puerto Rico. These changes include: (1) applying a new program delivery model; (2) instituting an accelerated award strategy for certain recipients; and (3) making the use of Public Assistance optional for certain projects.[9] These changes have expedited the obligation of funds. According to the GAO, as of January 15, 2021, FEMA had obligated $17.5 billion for 4,793 Public Assistance permanent work projects (See Exhibit A). However, the actual expenditure of funds remains painfully slow. According to the same GAO report, of the $17.5 billion obligated for permanent work projects, only $157.7 million, or 0.9%, had been spent as of January 15, 2021 (See Exhibit B). Finally, we note that as of early this year, more than three years after Hurricane Maria, FEMA was still developing cost estimates for 5,279 projects related to the 2017 hurricanes.[10]

HUD

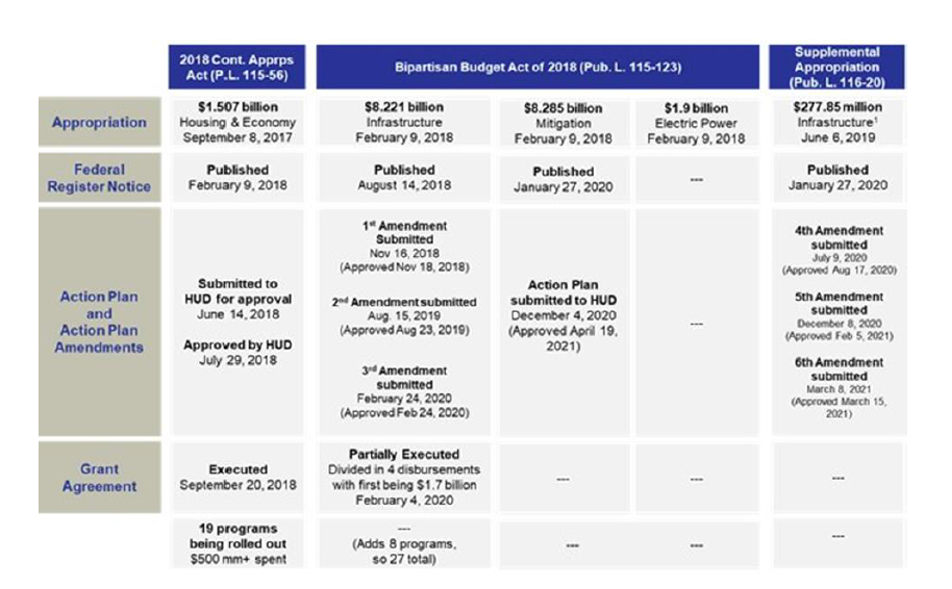

Between September 2017 and June 2019, Congress appropriated approximately $20.3 billion in CDBG-DR (Disaster Recovery) and CDBG-MIT (Mitigation) funds for disaster reconstruction and mitigation activities related to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico through three supplemental appropriation acts:

- P.L. 115-56: $1,507,179,000 for unmet needs;

- P.L. 115-123: $10,153,130,000 for unmet needs (including $1.9 billion to enhance and modernize the electric grid) and an additional $8,285,284,000 for mitigation activities; and

- P.L. 116-20: $304,000,000 for unmet needs.

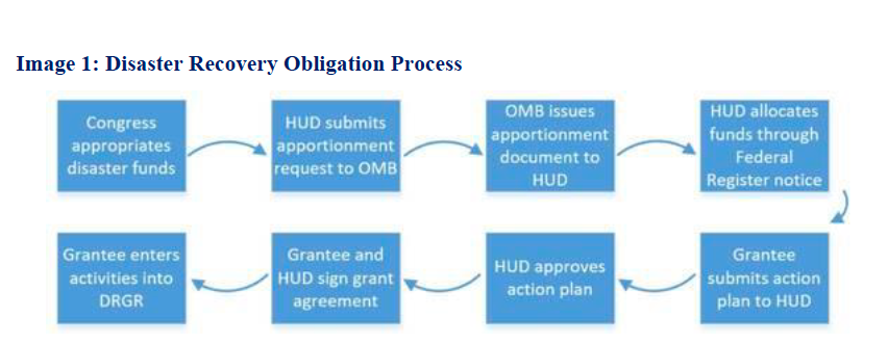

The usual process for disbursing these funds is somewhat cumbersome. As shown in Exhibit C, after Congress appropriates the money, OMB issues an apportionment document to HUD, and then HUD has to publish a notification in the Federal Register. The intended beneficiary then proceeds to draft an Action Plan for the use of the funds, in accordance with the published regulations. If and when the Action Plan is approved by HUD, then the parties need to execute a Grant Agreement to allow the expenditure of funds in accordance with the terms of the Action Plan.

However, as shown in Exhibit D, this process has been particularly, some would suspiciously, slow in the case of funds allocated for disaster relief and mitigation activities in Puerto Rico. A report issued by HUD’s Office of Inspector General (the “OIG Report”) on April 20, 2021 found that the Trump administration set up several bureaucratic obstacles that substantially slowed down the process for disbursing these funds.[11]

The OIG Report sets forth some particularly concerning findings regarding (1) the process prior to the publication of the Federal Registration notice for the use of $8.3 billion of mitigation funds and (2) revisions made to the CDBG-DR grant agreement which delayed the disbursement of $8.2 billion of disaster recovery funding for Puerto Rico’s unmet needs.

With respect to the Federal Register notice for the use of the $8.3 billion tranche for mitigation activities, the OIG Report describes months of negotiations between HUD and OMB, which resulted in several revisions of the notice’s text, mostly at the request of OMB. Several HUD officials found some of these OMB requests to be unreasonable or outside the scope of the normal administrative process. For example, Deputy Secretary Montgomery, during his OIG interview:

…characterized OMB’s revisions as containing “poison pills” because they would impose unworkable criteria and he was not sure it was “even legal” to insist upon grantees meeting the conditions as a prerequisite to receiving mitigation funding. For example, Montgomery said he did not believe that HUD could coerce Puerto Rico to fix its property-tax system to receive mitigation funding because the property-tax system was not related to mitigation activities. He also indicated that HUD did not put these types of conditions on other disaster-recovery grantees.[12]

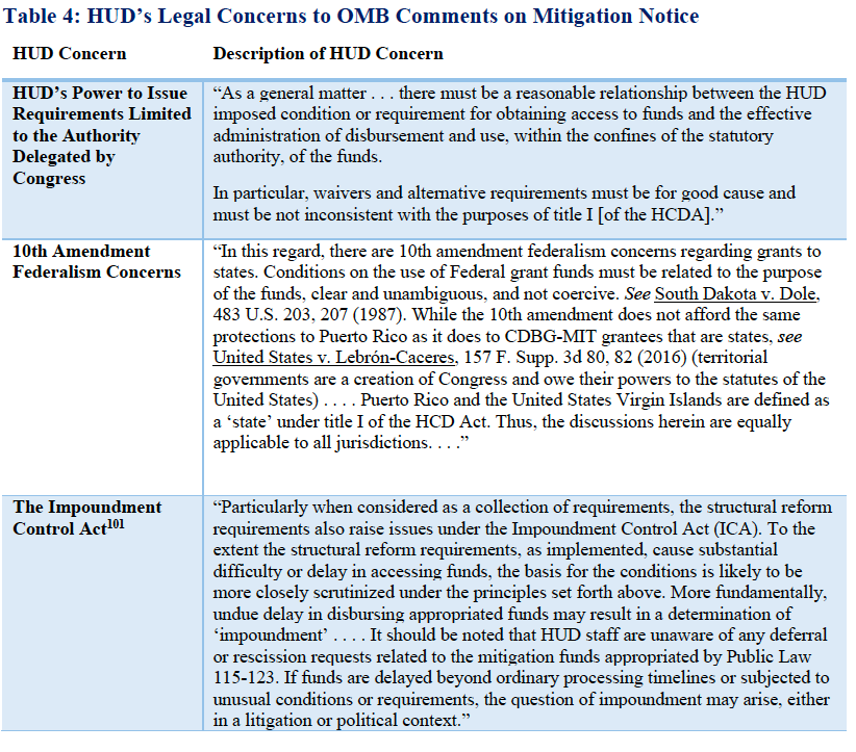

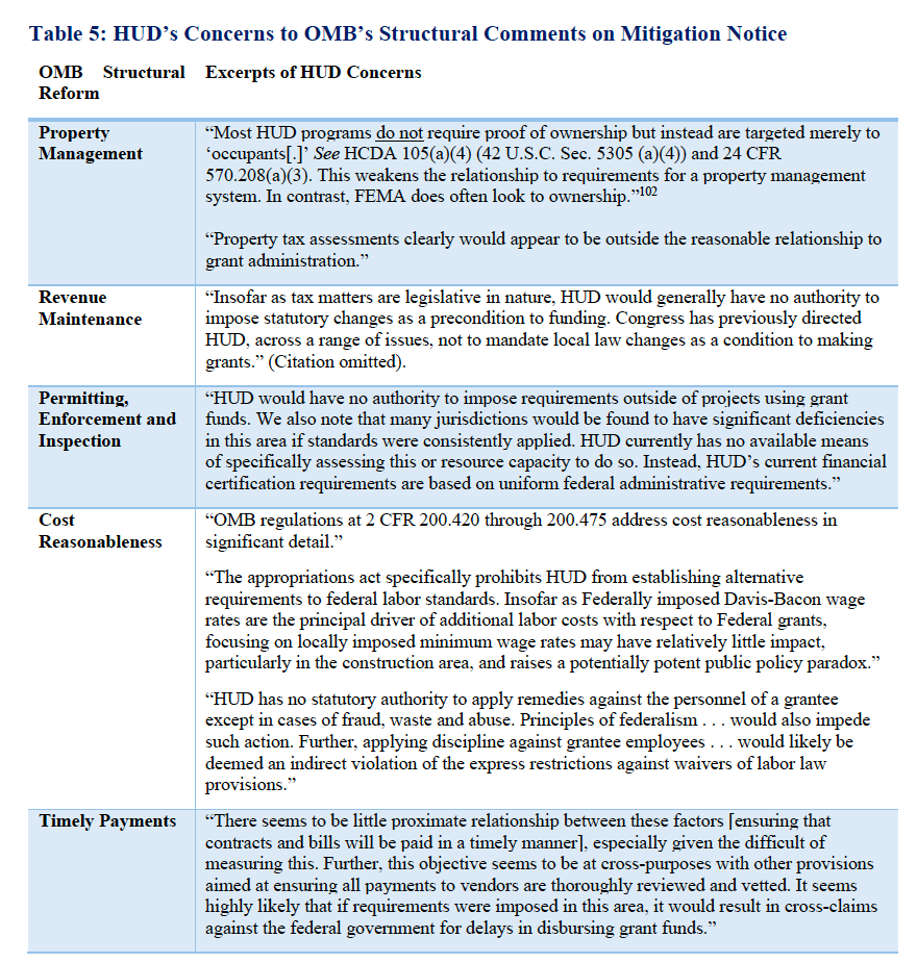

According to the OIG Report, HUD had both legal concerns as well as concerns regarding the structural (policy) changes that OMB wanted grant recipients to make. (See Exhibit E for a summary of the legal concerns and Exhibit F for a summary of the concerns regarding structural changes).

Furthermore, OMB requested the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs to review the proposed Federal Register notice, which a “HUD Attorney” described as “unheard of” for a disaster-related notice and stated that “HUD officials questioned whether the notice ‘truly qualified’ for OIRA review.”[13] Another senior HUD official described “OIRA’s comments as “kind of like Groundhog Day, just keeps coming back.”

The net result of loading the Federal Register notice text with “poison pills” and submitting it to unnecessary review by OIRA was that the mitigation notice for Puerto Rico was not filed until January 27, 2020 — “23 months and 19 days after the corresponding appropriation and 146 days after the statutory deadline.”[14] In contrast, “HUD published a notice for the other 14 eligible CDBG-MIT grantees 150 days earlier, on August 30, 2019, and a notice for the USVI 139 days earlier, on September 10, 2019, (dated September 4, 2019).”[15]

With respect to the revisions made to the CDBG-DR grant agreement for the disbursement of $8.2 billion of disaster recovery funding for Puerto Rico’s unmet needs:

The OIG also found that HUD’s decision to revise its template for CDBG-DR grant agreements was a factor in delaying disbursement of this second tranche of funding for unmet needs to PRDOH. In early 2019, HUD decided to substantially revise the content of its standard disaster-grant agreements, which at the time consisted of a brief three-to-six-page document that HUD considered to not have appropriately mitigated risk. While some senior HUD officials believed that these revisions were necessary, the revisions stemmed at least in part from OMB concerns related to PRDOH. During the grant-agreement revision process, it became clear to HUD staff that the agreement conditions needed to have parity with the CDBG-MIT notice conditions taking shape at the same time, thus making the obligation of the second tranche of funding for unmet needs dependent on completion of the Puerto Rico CDBG mitigation-notice negotiations. Accordingly, the protracted process for publishing the Puerto Rico CDBG-MIT notice contributed to a delay in finalizing the Department’s grant agreement with PRDOH for the second tranche of funding for unmet needs.[16]

The result was that HUD and Puerto Rico did not sign a grant agreement regarding this tranche of funds until February 21, 2020, while “Texas signed its grant agreement relating to second tranche funds 178 days earlier, on August 27, 2019, and Florida signed its agreement 150 days earlier, on September 24, 2019.”[17]

While all the circumstantial evidence points to OMB as the principal cause of the delays regarding the disbursement of CDBG funds to Puerto Rico, the OIG Report stops short of doing so, perhaps because senior OMB officials refused to cooperate with the investigation, while OMB itself denied requests for information made by the OIG. Nonetheless, former OMB head and then Acting Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney said the quiet parts at loud when, on an October 17, 2019 press conference regarding the Trump’s administration withholding of military aid to Ukraine, he stated the following:

Sure. I’ll – let’s deal with the second one first, which is – look, it should come as no surprise to anybody – the last time I was up here – I haven’t done this since I was Chief of Staff, right? The last time I was up here, some of you folks remember, it was for the budget briefings, right? And one of the questions y’all always asked me about the budget is, “What are you all doing to the foreign aid budget?” Because we absolutely gutted it, right? President Trump is not a big fan of foreign aid. Never has been; still isn’t. Doesn’t like spending money overseas, especially when it’s poorly spent. And that is exactly what drove this decision. I’ve been in the office a couple times with him, talking about this. And he said, “Look, Mick, this is a corrupt place.” Everybody knows it’s a corrupt place. By the way, put this in context: This is on the heels of what happened in Puerto Rico, when we took a lot of heat for not wanting to give a bunch of aid to Puerto Rico because we thought that place was corrupt… [18]

This statement is problematic in several ways. First, even if we take as valid the highly controversial proposition that the president can simply refuse to spend money legally appropriated by Congress for foreign assistance, the argument does not apply to Puerto Rico, which is under the domestic jurisdiction of the United States. Second, domestic disaster assistance is very different from foreign aid or military assistance. The primary purpose of the former is to affirmatively help people who have been adversely and directly impacted by a natural disaster, while the latter is primarily a tool to protect U.S. interests abroad and to further U.S. foreign policy objectives. Finally, we must note that as of the date of this hearing and to the best of our knowledge, no Puerto Rican government official has been indicted, much less convicted, of malfeasance regarding the use of federal disaster assistance funds. Ironically, the only persons or corporations implicated in corrupt activities with regard to Hurricane Maria’s reconstruction efforts, so far, are either federal government employees or incorporated in the mainland.

In addition to being wrong, it is also mind boggling that, consciously or not, the former head of OMB publicly admitted that what OMB had done in Puerto Rico, in withholding assistance to the victims of a natural disaster, was a direct precedent in support of the Trump’s administration decision to withhold assistance to Ukraine, in direct violation of duly enacted appropriations laws in both cases. And we all know how that Ukraine episode ended.

Conclusion

Nearly four years and three months after Hurricane Maria, the totality of the circumstances surrounding the federal government’s response to that natural disaster strongly suggests that it was arbitrary and capricious and that Puerto Rico was unreasonably treated in a different way relative to other jurisdictions affected by the 2017 natural disasters. However, we cannot conclude, with the information we have available at this moment (with the exception, perhaps, of Mr. Mulvaney’s rather candid statement), that it was the express intent of federal officials to discriminate against Puerto Rico in the disbursement of disaster assistance. But we can affirm with confidence that the impact and effects of the federal government’s actions have certainly been discriminatory, to the detriment and harm of thousands of Puerto Ricans.

The use of “poison pills”, unnecessary administrative reviews, and the imposition of unprecedented conditions on grant recipients, in the words of both the GAO and HUD’s OIG, resulted in undue delays in delivering assistance to disaster victims in Puerto Rico. These delays are not without cost, as the longer the reconstruction process takes, the harder it is to return to a pre-disaster normality. We must remember that we are dealing with human beings that have a natural desire, in many cases, to return to “the way things used to be.”

That, unfortunately, may not be possible in Puerto Rico, due to these unfair delays affecting the recovery process. As time goes by after a disaster, old neighbors may decide to move to other parts of Puerto Rico; the widow who used to live in the house down the street may have relocated to the mainland to live with one of her children; the convenience store down by the corner may have gone bankrupt; families may have separated; friendships lost; students transferred to other schools; little league teams disbanded; budding love affairs broken; businesses large and small closed forever, and so on and so forth.

We must note that both FEMA and HUD have undertaken important actions to speed up the obligation of funds and to improve their working relationship with the Puerto Rican government over the last year or so. These are welcome developments. However, difficult questions remain unanswered: Who and how do we decide to spend this federal windfall? What do we preserve, what do we leave to waste, and who decides? Who is deemed “worthy” of help, why, what kind, and from whom? For instance, Which coastal community gets a seawall and which community is relocated to a “safer area”?; Whose neighborhood gets razed to the ground, displaced, or gentrified in the name of “redevelopment”?; Where do we build new public schools, hospitals, and electric, water, and telecommunications infrastructure, and who decides?

These are only some of the thorny questions we will face as we move forward with the reconstruction of the island. It is good to keep them in mind because they remind us that these are political decisions in no way preordained or inevitable in the wake of Hurricane Maria. As Horowitz reminds us: “The etymology of the word disaster refers to stars out of alignment; but if the changes in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina seemed to some to proceed with the force of destiny, it is well to remember as Shakespeare cautioned, ‘The fault…is not in our stars, But in ourselves, that we are underlings’.”[19]

In the end, then, the shape of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria will depend to a large extent on how we address long-standing issues of class, race, segregation, poverty, inequality, and political power that we have ignored for far too long.

We thank once again the United States Commission on Civil Rights for the opportunity to participate in these hearings and look forward to answering any questions Commission members may have at this time.

Respectfully submitted,

Sergio M. Marxuach

Policy Director

Center for a New Economy

Endnotes

[1] United States Government Accountability Office, 2017 Hurricanes and Wildfires: Initial Observations on the Federal Response and Key Recovery Challenges, GAO-18-472, (Washington, DC: September 2018), p. 29.

[2] Government of Puerto Rico, Transformation and Innovation in the Wake of Devastation: An Economic and Disaster Recovery Plan for Puerto Rico, (San Juan, PR: August 2018), pp. 41-44.

[3] Bernard Yaros, The Economics of Puerto Rico’s Post María Recovery, Moody’s Analytics, September 2018, pp. 1-4.

[4] The FEMA estimate is taken from the 2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report, (Washington, DC: July 12, 2018), p. 1; the estimate from the Government of Puerto Rico is set forth in Transformation and Innovation in the Wake of Devastation, supra, n. 2, p. 159.

[5] United States Government Accountability Office, Puerto Rico Recovery: FEMA Made Progress in Approving Projects, But Should Identify and Assess Risks to the Recovery, GAO-21-264, (Washington, DC: May 2021), p. 14.

[6] GAO, 2017 Hurricanes and Wildfires, supra n. 1., at p. 18 (emphasis by the author).

[7] Id. at p. 56 (emphasis by the author).

[8] GAO, Puerto Rico Recovery: FEMA Made Progress in Approving Projects, supra n. 5, p. 18 and p. 22.

[9] Id. at p. 19.

[10] Id. at p. 25.

[11] Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Review of HUD’s Disbursement of Grant Funds Appropriated for Disaster Recovery and Mitigation Activities in Puerto Rico, April 20, 2021. See also, Tracy Jan and Lisa Rein, “Investigation suppressed by Trump administration reveals obstacles to hurricane aid for Puerto Rico”, Washington Post, April 22, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/04/22/puerto-rico-hurricane-trump-hud/ .

[12] HUD OIG Report, p. 25.

[13] Id. at p. 30.

[14] Id. at p. 21.

[15] Id. at p. 43.

[16] Id. at p. 42.

[17] Id.

[18] White House Acting Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney Press Briefing, October 17, 2019, available at https://www.c-span.org/video/?465446-1/mick-mulvaney-defends-withholding-military-aid-ukraine-pending-investigation, the quoted segment begins at minute 19:41 of the video.

[19] Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1915-2015, (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2020), p. 5.

Exhibit A

Source: United States Government Accountability Office, Puerto Rico Recovery: FEMA Made Progress in Approving Projects, But Should Identify and Assess Risks to the Recovery, GAO-21-264, (Washington, DC: May 2021), p. 27.

Exhibit B

Source: United States Government Accountability Office, Puerto Rico Recovery: FEMA Made Progress in Approving Projects, But Should Identify and Assess Risks to the Recovery, GAO-21-264, (Washington, DC: May 2021), p. 29.

Exhibit C

Source: Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Review of HUD’s Disbursement of Grant Funds Appropriated for Disaster Recovery and Mitigation Activities in Puerto Rico, April 20, 2021, p. 10.

Exhibit D

Source: Fiscal Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, Disclosure Statement for the Seventh Amended Title III Joint Plan of Adjustment for the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico et. al., July 30, 2021, p. 147.

We note that HUD published the Federal Register notice for the use of the $1.9 billion allocated by Congress for work on Puerto Rico’s grid on June 22, 2021. The Puerto Rico Housing Department has published a first draft of the Action Plan for the use of those funds, which is currently subject to public review and comment.

Exhibit E

Source: Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Review of HUD’s Disbursement of Grant Funds Appropriated for Disaster Recovery and Mitigation Activities in Puerto Rico, April 20, 2021, p. 26.

Exhibit F

Source: Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Review of HUD’s Disbursement of Grant Funds Appropriated for Disaster Recovery and Mitigation Activities in Puerto Rico, April 20, 2021, p. 27.