Analysis of PREPA Legacy Assets Public-Private Partnership Agreement

Published on March 15, 2023

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Structure of the Generation O&M Agreement

- Expected Savings

- Market Structure

- Buy Local Provisions

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Introduction

On January 24, 2023, the Puerto Rico Power Electric Authority (“PREPA” or the “Owner”), the Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnerships Authority (the “P3 Authority” or the “Administrator”), and Genera PR LLC (the “Operator” or “Genera”), executed the Puerto Rico Thermal Generation Facilities Operation and Maintenance Agreement (the “Generation O&M Agreement”) setting forth the terms and conditions pursuant to which the Operator will operate, maintain, and eventually decommission certain Legacy Generation Assets owned by PREPA.

The execution of the Generation O&M Agreement is the most recent step in the long-term transformation of the Puerto Rico electricity market. Some of the highlights of that transformation process are:

- The enactment of Act 57 on May 17, 2014, creating the Puerto Rico Energy Commission (now the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau or the “PREB”) to regulate the electricity market in Puerto Rico, among other things;

- The filing of a petition to restructure PREPA’s financial liabilities pursuant to Title III of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (“PROMESA”) in July 2017, a proceeding that is still pending resolution before the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico;

- The enactment of Act 120 on June 21, 2018 to “establish a path for a more reliable, efficient, and low-cost electric system”;

- The enactment of Act 17 of April 11, 2019 setting forth “the Puerto Rico Energy Public Policy”; and

- The execution of the Transmission and Distribution Operation and Management Agreement (the “T&D O&M Agreement”) entered into on June 22, 2020, by and among PREPA, the Administrator, LUMA Energy LLC and LUMA Energy ServCo, LLC (collectively, the “T&D Operator” or “LUMA”), pursuant to which the T&D Operator “shall operate, maintain, and modernize PREPA’s transmission and distribution system (the “T&D System”).

This ten-year transformation process was prompted by PREPA’s failure to provide affordable, reliable, and efficient electric service to the people of Puerto Rico after decades of mismanagement, corruption, and non-compliance with applicable laws, regulations, and industry standards.

Indeed, according to the P3 Authority PREPA currently faces significant operational challenges, including in the following areas:

- Safety — Since 2003, “PREPA’s safety performance has been more than five times worse that the industry average. Incident Rates for T&D and generation on an annual basis have ranged from 11.0 to 19.0, and averaged approximately 15.0; this compares to a U.S. average for public power [companies] of approximately 4.92.”[1]

- Reliability — PREPA’s plants operate with Forced Outage Rates that are up to five times worse than the industry average and at low Equivalent Availability Factors, which increases “the likelihood of forced outages leading to an interruption of the delivery of electricity to customers. Indeed, some of these outages resulted in inadequate generation supply and significant loss of adequate power supply to meet customer demand.”[2]

- Generation Resource Adequacy — Puerto Rico has inadequate supply resources to meet expected demand. In fact, “the load loss expectation for Puerto Rico for 2023 was calculated at 8.81 days per year, which is 88 times higher than the utility industry benchmark of 1 day in 10 years or 0.10 days per year. This means that there will be 8.81 days per year when demand will not be met by generation supply.”[3]

- Environmental Compliance — PREPA’s record of environmental compliance has been deficient, not to say outright awful. Throughout its history it has failed to comply with the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, and with several other air and water environmental rules and regulations. As a result, the “Legacy Generation Assets continue to operate at significantly lower capacity than their nameplate capacity and suffer from long-standing operational deficiencies and disrepair.”[4]

- Corruption — PREPA has long been a source of private and public corruption in the island. PREPA’s suppliers, in many cases thanks to their political donations and influence, have benefited from contracts to provide goods and services to the public utility, sometimes at inflated, not to say borderline extortionate, prices. See, for example, the nefarious history of PREPA’s fuel and equipment procurement practices.[5]

It has become fashionable in certain circles of the self-described political avant-garde to claim that PREPA was once considered the “crown jewel” of Puerto Rico’s government (a particularly obnoxious figure of speech given our colonial history). A closer look at the historical record, though, reveals that for many years appointment to senior management positions at PREPA depended more on partisan politics than on personal merit. Technical and managerial decisions, in turn, were often subordinated to short-term political interests. PREPA survived for decades largely by postponing capital expenditures, delaying payment to suppliers, using accounting gimmicks to muddle its true financial condition, and by borrowing billions at relatively low, tax-exempt rates in the U.S. municipal bond markets, in many cases just to make the debt service on other maturing debt. That all these shenanigans eventually ended in a bankruptcy filing should not be surprising to anyone that was paying attention. Nonetheless, it is still difficult to think of other monopolies that have managed to bankrupt themselves, with the exception, perhaps, of the state-owned enterprises in the former Soviet Union.

Given all of the above, the incontrovertible conclusion is that PREPA simply cannot continue operating the way it has up until now. It has become a decrepit, some would say half-dead, zombie public utility that stifles economic activity in Puerto Rico. The time has come to take drastic action with respect to PREPA, as it has proven incapable of reforming itself and has been immune to the efforts of several administrations to modernize and improve its operations. Those who would infuse this moribund public corporation with the breath of new life bear the burden of proof to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence why that should be the case.

In this Policy Brief, we will present an analysis of the principal components of the Generation O&M Agreement, including the basic structure of the transaction; the compensation of the Operator (including any incentives and penalties provided for therein); the estimated savings to be generated as a result of hiring a private operator to operate and maintain the Legacy Generation Assets; the planned decommission of most of the existing facilities that currently use fossil fuels to generate electricity in Puerto Rico; and the resulting structure of Puerto Rico’s electricity market.

Structure of the Generation O&M Agreement

Genera is a wholly-owned subsidiary of New Fortress Energy (“NFE”). NFE, in turn, is “an integrated gas-to-power energy infrastructure company”, whose “business model spans the entire production and delivery chain from natural gas procurement and liquefaction to shipping, logistics, facilities and conversion or development of natural gas-fired power generation.”[6]

Genera is being hired by PREPA, as owner of the Legacy Generation Assets, to provide (either directly or through subcontractors) four classes of services, namely: (i) the Mobilization Services, (ii) the O&M Services commencing on the Service Commencement Date, (iii) the Decommissioning Services, and (iv) the Demobilization Services. In exchange for providing those services, the Operator is entitled to receive certain compensation, subject to any applicable Incentive Payments or Penalties, during the term of the Generation O&M Agreement, which is initially expected to last ten (10) years.

The Mobilization Services

The Operator is required to provide a specific set of services during the period between the Effective Date of the Generation O&M Agreement and the O&M Services Commencement Date, which is expected to be about 100 days after the Effective Date (the “Target Service Commencement Date”). The Mobilization Services, which are described in the Mobilization Plan outline set forth in Annex VII to the Generation O&M Agreement, are intended to “ensure an orderly transfer of the care, custody and control of the Legacy Generation Assets to Operator”.[7]

Those services include, among others, the evaluation and hiring of personnel; the hiring of subcontractors, if any; executing the tasks set forth in the Handover Checklist included in Annex VII; obtaining the requisite insurance; preparing a Procurement Manual; developing a Communications Plan; preparing a Fuel Optimization Plan, setting forth the Fuel Cost Savings Initiatives; and preparing a Federally Funded Generation Project Plan “listing and describing those projects proposed by Operator for priority in the receipt of any funding for the Legacy Generation Assets, received or to be received by or for the benefit of Owner from any U.S. federal agency.”[8]

During the Mobilization Period the Operator is entitled to be reimbursed for all reasonable costs and expenses (including the compensation of current employees of the Operator and any subcontractors) incurred during the course of providing the Mobilization Services, subject to a cap of $15 million. [9] If the Target Service Commencement Date is delayed by 90 days or more, except in the case of a Force Majeure Event or an event caused by Owner’s fault, then the Operator shall pay damages to PREPA in the amount of $1 million per week for each week the Target Service Commencement Date is further delayed, up to a maximum of $15 million.[10]

The O&M Services

Commencing on the Service Commencement Date, Operator shall (i) provide management, operation, maintenance, repair, restoration, replacement, and other related services for the Legacy Generation Assets, as well as any optimization procedures (including for improving fuel and efficiency) approved by the PREB, and (ii) establish policies, programs and procedures with respect thereto, to the extent not already established.[11]

The scope of the O&M Services is set forth in Annex IX to the Generation O&M Agreement. These services include, but are not limited to, the following:

(1) day-to-day operation and maintenance (including any major maintenance) services, including operation of the Legacy Generation Assets to generate electricity and deliver it into the T&D System;

(2) identifying, justifying and managing any required maintenance capital expenditures;

(3) providing routine inspections of the Legacy Generation Assets;

(4) providing annual operating tests (the Annual Performance Test) of the Legacy Generation Assets in coordination with T&D Operator;

(5) establishing appropriate and customary safety work rules and practices;

(6) developing an operation and maintenance training program;

(7) provisioning, storing and maintaining the inventory of spare and consumable parts, including Capital Spare Parts, for the Legacy Generation Assets;

(8) establishing and maintaining a computerized maintenance management system for the Legacy Generation Assets;

(9) performing scheduled and emergency maintenance, repair and replacement of equipment, including any balance of plant equipment, painting, and cleaning, among others;

(10) managing Planned Outages, Unplanned Outages and Forced Outages and restoration of power supply to the transmission grid;

(11) coordinating business continuity and emergency planning and storm restoration and recovery in coordination with T&D Operator;

(12) procuring and managing water or auxiliary power supply, as applicable;

(13) maintaining and repairing fuel and water systems, including tanks, pumps, filters, and piping, as required;

(14) procuring and managing the delivery and quality testing of fuel;

(15) liaising with the T&D Operator or any of their assignees or successors regarding dispatch, dispatch planning and related T&D system matters and providing required information;

(16) interfacing with and providing reports to regulators including PREB and with environmental compliance agencies such as the EPA, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and others, as may be required;

(17) obtaining, complying with and maintaining licenses, permits, consents and the Consent Decree, as necessary;

(18) providing periodic reports regarding programmed and non-programmed operations, maintenance, repairs, services and modifications performed and to be performed;

(19) preparing for and assisting in, or subcontracting for and overseeing, the decommissioning of the relevant plants as outlined in the Integrated Resource Plan (including any future integrated resource plans) in coordination with PREPA/the T&D Operator, Owner and PREB;

(20) participating in emergency planning and drills led by the T&D Operator, as needed;

(21) conducting emergency planning and drills independent of T&D Operator;

(22) assisting with the transition of the plants to third parties or to new uses (synchronous condensers, etc.) to the extent certain of the plants are removed from the O&M Agreement; and

(23) developing and maintaining a good neighbor program.[12]

Genera has already stated it will make extensive use of subcontractors to perform the O&M Services; specifically it intends to hire the PIC Group, “a global power and energy service provider”, and Black & Veatch, “an engineering, procurement, and consulting construction firm”.

Compensation for the O&M Services

Pass-Through Expenditures — The Operator shall be reimbursed for any reasonable and documented costs and expenses incurred by the Operator in connection with the performance of its obligations pursuant to the Generation O&M Agreement, including employee compensation, the cost of all subcontracted and seconded employees, the cost of professional services, insurance premiums, any taxes owed to the Commonwealth or any municipality, and fuel costs, among other costs and expenditures set forth in Annex XII to the Generation O&M Agreement.

However, Pass Through Expenditures do not include Disallowed Costs, as such term is defined in Section 7.7(a) of the Generation O&M Agreement, including but not limited to, any costs incurred as a consequence of the Operator’s gross negligence or willful misconduct; any fines or penalties imposed on the Operator by a governmental body; any expenditures in excess of the approved Operating Budget then in effect; or Operator Overhead costs which are included in the applicable Service Fee.[13]

O&M Fixed Fee — In addition, in exchange for providing the O&M Services, the Operator is entitled to receive an annual O&M Fixed Fee in the amount of $22.5 million, adjusted for inflation (subject to a 3% annual cap), during the term of the Generation O&M Agreement.[14]

Adjustments to the O&M Fixed Fee Upon Decommissioning of Assets — Commencing in contract year 6, the O&M Fixed Fee shall be gradually reduced to take into account the decommissioning of generation assets, subject to a $5 million floor. The amount of this reduction is calculated pursuant to a formula set forth in Section I.B. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement. Incentive Payments and Penalties are also adjusted on a pro-rata basis as the O&M Fee is gradually adjusted to account for the decommissioning of the Legacy Generation Assets.

O&M Services Incentives and Penalties — During each contract year the Operator is (i) eligible to receive additional financial compensation in the form of an Incentive Payment and (ii) subject to the payment of potential Penalties, in each case based on the Operator’s performance in providing the O&M Services. For each contract year the aggregate amount of any Incentive Payments minus any Penalties shall not exceed $100,000,000, provided, however, that any excess over that amount carries over to the next contract year.[15] An amount equal to the maximum amount of the Incentive Payments available in any given Contract Year shall be included in the Operating Budget for that year. If any Penalties are determined to be due, then in accordance with Section 7.1(c)(v) of the Generation O&M Agreement, PREPA shall deduct the Penalty from the next payment of the applicable Service Fee due to the Operator following such determination.

The Operator’s performance of the O&M Services will be evaluated in six categories: (1) Operation Cost Efficiency, (2) Equivalent Availability Factor (“EAF”), (3) Safety Compliance, (4) Environmental Compliance, (5) Reporting Obligations and (6) Fuel Savings, as set forth in Section III.B of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

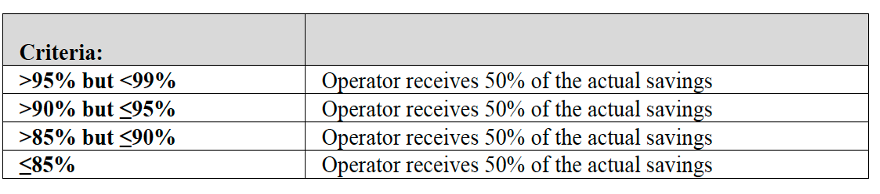

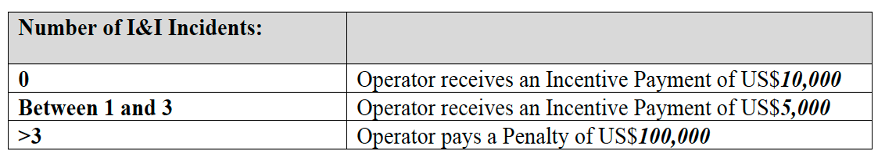

- Operation Cost Efficiency — The Operator’s cost efficiency will be measured using the applicable Operating Budget as the benchmark. Operator shall receive an O&M Incentive Payment based on a percentage of the total amount of cost savings achieved by the Operator in the delivery of the O&M Services, if any, as compared to the approved Operating Budget. The measurement parameter for this Incentive Payment consists of actual expenditures incurred as a percentage (%) of the approved Operating Budget, where actual savings equal the Operating Budget minus actual expenditures. The table below sets forth the criteria for payment:

Source: Section III.B.1. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

- Equivalent Availability Factor — In general, the availability factor of a power plant is the amount of time that it is able to produce electricity over a certain period, divided by the amount of the time in the period. For purposes of the Generation O&M Agreement, the term Equivalent Availability Factor (“EAF”) is defined as:

EAF = (AH-EPDH-EUDH) x 100 %

PH

where:

-

- AH = Available Hours

- EPDH= Equivalent Planned Derated Hours

- EUDH = Equivalent Unplanned Derated Hours

- PH = Period Hours or number of hours that the Legacy Generation Asset was in active state

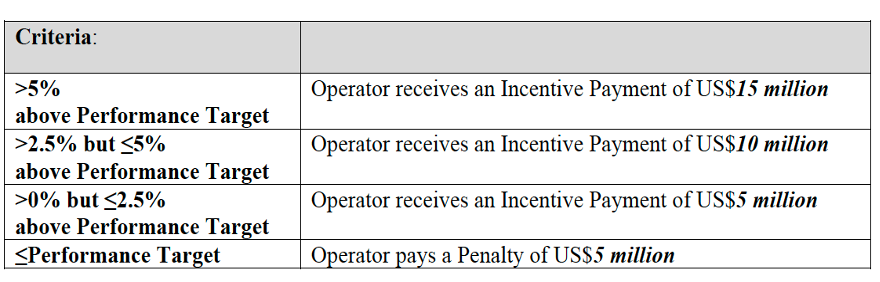

For every contract year, the target EAF will be calculated for each baseload and peaking unit pursuant to an annual performance test to be carried out pursuant to Section 5.22 of the Generation O&M Agreement.[16] Incentive Payments or Penalties, as the case may be, will be calculated in accordance with the criteria set forth below.

For Baseload Units:

Source: Section III.B.2. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

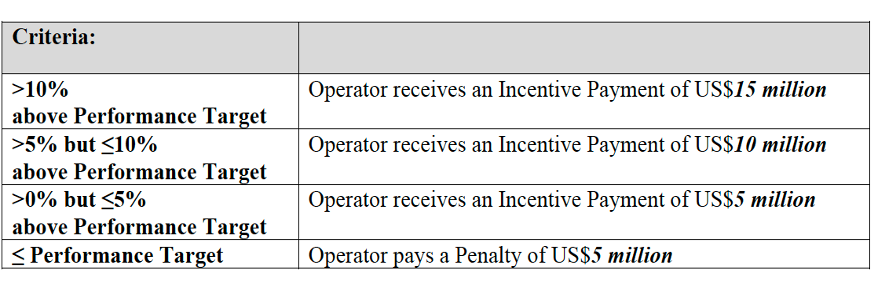

For Peaking Units:

Source: Section III.B.2. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

The Minimum Performance Threshold for the annual EAF for the applicable Baseload Units and for the Peaking Units shall be established pursuant to Section 5.22 of the Generation O&M Agreement. Failure by the Operator to achieve either Minimum Performance Threshold in two (2) consecutive Contract Years shall trigger a Minimum Performance Threshold Default pursuant to Section 14.1(l) of the Generation O&M Agreement.[17]

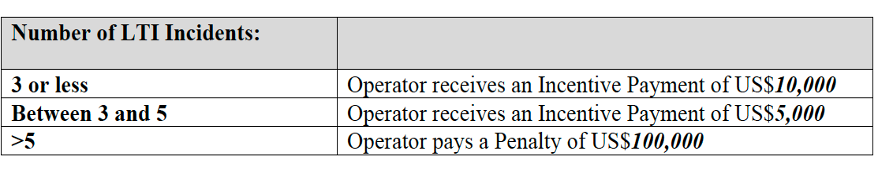

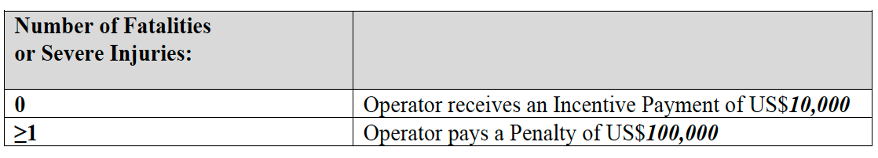

- Safety Compliance — Operator shall receive an Incentive Payment or be subject to a Penalty based on its performance for each contract year with respect to the safety compliance targets described below.

OSHA Lost Time Incidents (“LTI”):

Source: Section III.B.3. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

OSHA Recordable Injury or Illness (“I&I”):

Source: Section III.B.3. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

OSHA Fatality or Severe Injury:

Source: Section III.B.3. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

For each contract year, the maximum aggregate Penalty that the Operator may incur shall be US$100,000, in each case with respect to the parameters of the Safety Compliance category. The payment of penalties by Operator on any of the safety compliance measurement parameters in two (2) consecutive Contract Years shall trigger a Minimum Performance Threshold Default pursuant to Section 14.1(l) of the Generation O&M Agreement.

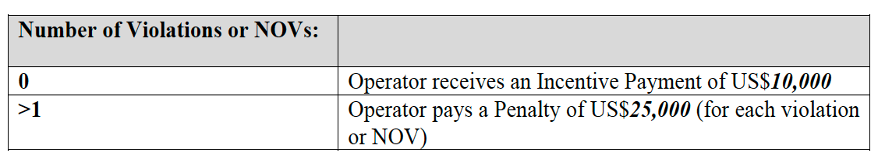

- Environmental Compliance — The Operator shall receive an Incentive Payment or be subject to a Penalty based on its performance with respect to the environmental targets described below.

Violation of Consent Decrees and/or Notice of Violations (NOVs):

Source: Section III.B.4. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

For each contract year, the maximum aggregate Penalty that the Operator may incur shall be US$100,000, in each case with respect to the parameters of the Environmental Compliance category. The payment of a Penalty by Operator under the Environmental Compliance category for two (2) consecutive contract years shall trigger a Minimum Performance Threshold Default pursuant to Section 14.1(l) of the Generation O&M Agreement.

- Reporting Obligations — Operator shall be subject to a charge based on its timeliness in responding to a reasonable request for information from the Administrator. For every fifteen (15) sequential days during which the Operator fails to provide a response to Administrator, Operator shall pay a penalty of US$100,000, up to a maximum aggregate of $1 million for each contract year.[18]

- Fuel Optimization — Operator shall receive a “Fuel Optimization Payment” of fifty percent (50%) of any Actual Fuel Savings achieved during the relevant contract year.[19] For the purpose determining Actual Fuel Savings and the corresponding Fuel Optimization Payment for any contract year that commences after one or more Fuel Cost Savings Initiatives have been implemented or are otherwise already accounted for in the relevant Budget, the Budgets for such contract year(s) shall include an addendum setting forth hypothetical budget allocations for the Fuel Costs that would be incurred in the absence of the Fuel Cost Savings Initiatives.[20] The detailed methodologies to be used to calculate Actual Fuel Savings and any Fuel Optimization Payment shall be included in the Fuel Optimization Plan to be developed during the Mobilization Period.

Decommissioning Services

In general, the Decommissioning Services are services provided pursuant to the Generation O&M Agreement to complete the dismantlement and removal of the structures comprising PREPA’s Legacy Generation Assets, and all other activities indispensable for the retirement, dismantlement, decontamination or storage of the legacy generation assets.

At any point after the Service Commencement Date, the Administrator may deliver to the Operator a decommissioning notice to commence the Decommissioning Services for one or more of the Legacy Generation Assets. In addition, in the event that the Operator determines that all or a portion of a Legacy Generation Asset cannot continue to be safely operated and maintained, the Operator may deliver to the Administrator and the PREB a request to commence Decommissioning Services for the applicable Legacy Generation Asset.[21]

Once the parties agree that a Legacy Generation Asset or Assets will be decommissioned, then the Operator shall prepare a Decommissioning Plan consistent with the Decommissioning Plan outline set forth in Annex XV to the Generation O&M Agreement.

The Decommissioning Plan shall provide for:

- the permitting, demolition, decontamination, waste disposal and dismantling/or preparation for conversion to such other future use as the Administrator and the PREB may designate, as applicable, of the Legacy Generation Asset, and waste disposal, for achievement of end-state conditions within a prescribed time;

- the development of the Decommissioning Budget, as set forth in Section 16.2 of the Generation O&M Agreement;

- reasonably acceptable arrangements to facilitate the transition of the Operator employees, into new jobs or industries, including a training and/or severance plan (to be funded by the Owner) for any Operator Employees not hired into a successor job or industry; and

- a timeline setting forth when Decommissioning Services shall be provided, including the date on which the Decommissioning Services shall commence and the date on which the Decommissioning Services for such legacy generation asset shall be completed.[22]

Compensation for Decommissioning Services

Once an asset has been selected for decommissioning the parties have to agree on the Decommissioning Budget for that asset. The Decommissioning Budget, subject to the approval of the Administrator and in certain cases the PREB, will include all the Pass-Through Expenditures the Operator expects to incur in connection with the decommissioning process.

The Owner then will pay the Operator all Pass-Through Expenditures required to perform the Decommissioning Services and shall continue to pay the O&M Fixed Fee in full (subject to any applicable adjustments) for the duration of the term of the Generation O&M Agreement.

The Operator could earn an Incentive Payment or incur a Penalty based on the Operator’s performance of the Decommissioning Services.[23]

Decommissioning Services Incentives and Penalties — The Operator’s performance of the Decommissioning Services will be evaluated in the category of Operation Cost Efficiency. Upon completion of the Decommissioning Services with respect to any decommissioned legacy asset:

- If (i) the Operator’s actual expenditures are consistent with or exceed the estimates included in the applicable Decommissioning Budget and (ii) the Operator successfully completes the applicable Decommissioning Services on or before the relevant Decommissioning Completion Date, no Incentive Payment shall be applicable.

- If (i) the Operator’s actual expenditures are below the estimates included in the applicable Decommissioning Budget and (ii) the Operator successfully completes the applicable Decommissioning Services on or before the relevant Decommissioning Completion Date, the Operator shall be eligible to receive a Decommissioning Incentive Payment consisting of a percentage of the actual cost reduction as compared to the estimates included in the applicable Decommissioning Budget.[24]

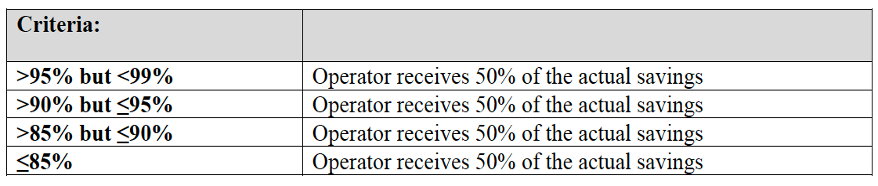

The performance of the Operator in executing the Decommissioning Services will be measured by calculating the actual expenditures as a percentage (%) of the approved Decommissioning Budget, where actual savings equal the Decommissioning Budget minus actual expenditures, as set forth in the table below:

Source: Section III.C.1. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement

- If the Decommissioning Services with respect to a Legacy Generation Asset are not completed by the applicable Decommissioning Completion Date, then Operator shall be subject to a Decommissioning Penalty consisting of one million dollars ($1,000,000) for each week by which the completion of the Decommissioning Services is delayed past the applicable Decommissioning Completion Date, up to a maximum of fifteen million dollars ($15,000,000) in the aggregate across all Legacy Generation Assets and Generation Sites.[25]

- In the event the Operator (i) exceeds the costs and expenses included in the applicable Decommissioning Budget and/or (ii) fails to complete the Decommissioning Services before the Decommissioning Completion Date for any two (2) Legacy Generation Assets, the Administrator may, in its sole discretion, engage an independent third party to perform any future Decommissioning Services with respect to any Legacy Generation Assets without either Party incurring, or becoming liable for, the payment of any penalty, premium or termination fee.

Demobilization Services

The Operator shall provide certain Demobilization Services upon the expiration or early termination of the Generation O&M Agreement to ensure the orderly transfer of any remaining Legacy Generation Asset from the Operator to the Owner or to a successor operator. The Operator has agreed to perform the Demobilization Services in accordance with a Demobilization Plan to be developed in accordance with the requirements set forth in Annex XVI to the Generation O&M Agreement.

In general, “the Demobilization Plan shall enable the seamless, safe, and effective transfer of the Legacy Generation Assets to the Owner, the Administrator, or their successor operator. The Operator’s principal objective shall be to complete any demobilization activities in the time frame and on the terms that are most suitable to Owner and Administrator in a way that will achieve an orderly handover or return of the Legacy Generation Assets.”[26]

Compensation for the Demobilization Services

During the Demobilization Period, which is estimated to last about a year, the Operator is entitled to receive a “Demobilization Service Fee”. The Demobilization Service Fee shall be an aggregate amount equal to:

- the hourly fully allocated cost rate for each category of Operator employee or Affiliate personnel providing Demobilization Services multiplied by

- the number of hours worked by each Operator employee or Affiliate personnel in such category providing Demobilization Services, plus

- ten percent (10%) of the product of (i) and (ii), plus

- all other reasonable and documented costs and expenses incurred by Operator (without markup for Operator profit) that are necessary and reasonable in the course of providing the Demobilization Services and/or implementing the Demobilization Plan, including the cost of any Subcontractors providing Demobilization Services.[27]

Expected Savings

As we have seen above, the Generation O&M Agreement contains a fairly well-developed set of incentives, penalties, and performance metrics to evaluate the performance of the Operator. In this sense, the Generation O&M Agreement is an improvement over the T&D O&M Agreement.

Indeed, the inclusion of measurable benchmarks, the requirement to engage in good faith negotiations with current PREPA employees, the cap on the fees that the Operator can earn during the Mobilization Period, and other requirements set forth in the Scope of O&M Services, for example the obligation to develop a fully fleshed out communications plan prior to the handover of operations to the Operator, demonstrates that governments can and indeed do learn from prior experiences, notwithstanding what anti-government zealots may say or think to the contrary.

Having said that, though, the fact remains that executing and entering into the Generation O&M Agreement makes sense only if the expected savings to be generated exceed the expected costs of the agreement. The government of Puerto Rico has stated that it expects to generate “significant savings” from transferring the operation and management of the Legacy Generation Assets to Genera. However, the evidence it offers to back up that assertion is rather thin, as we will demonstrate below.

The P3 Authority hired FTI Consulting (“FTI”) to carry out an analysis of the expected benefits of selecting a third party operator for the Legacy Generation Assets. FTI set forth its findings in a report (the “FTI Report”) that is included as Exhibit B to the P3 Report, which the P3 Authority is statutorily required to prepare and publish in connection with the execution of any public-private partnership transaction.

According to the FTI Report:

- Genera estimates achievable O&M savings of $19 million per year, mostly from labor and more efficient maintenance activities.

- Genera also estimates fuel savings (without plant conversions or equipment replacement) of approximately $85 million per year, “which would come from optimizing existing fuel contracts” ($56 million), “achieving better risk and credit terms on the existing oil contracts” ($20 million), and “making operational changes at the Legacy Generation Assets to increase fuel efficiency” ($9 million).

- Genera also “believes” that, subject to PREB approval, “there are additional fuel savings”, in excess of $100 million, “achievable through fuel conversion of units”…These “conversions would involve commissioning of gas fuel operation for units that are dual fuel capable or conversions of units that are able to be converted.”

- The “combined estimated savings from O&M and fuel range from $100 million to $200 million annually (including conversion savings if approved by PREB).” Under the terms of the Generation O&M Agreement those “savings would be shared 50%/50% between Genera and the electric ratepayers of Puerto Rico. That would result in $50 million to $100 million per year to Puerto Rico electric system customers.”

- In sum, concludes FTI, “Puerto Rico is guaranteed a benefit and Genera’s incentive compensation pays for itself. Given the low fixed fee, high incentive fee component and the 50%/50% sharing of [the savings], Genera is more than motivated to perform and operate the plants well and as fuel-efficiently as possible.”[28]

So, according to FTI’s analysis this transaction is a clear win-win situation and everybody will live happily ever after the Effective Date. Pardon our skepticism, but it seems to us that FTI is being too clever by half, as the British would say.

First, FTI relies on representations made by Genera to the Partnership Committee and the P3 Authority and their advisors. There is no indication, at least in the text of the FTI Report, that FTI carried out an independent evaluation or executed any standalone due diligence to validate or verify Genera’s claims of expected savings.

Second, even if it is arguably reasonable to take Genera’s representations at face value, FTI should have requested that Genera provide the documentation of the methodology it used to calculate those expected savings. However, the FTI Report includes no explanation of the assumptions, the methodology used, or the variables analyzed by Genera to estimate expected savings. The people of Puerto Rico, in essence, are being asked to believe these ostensible savings on faith alone.

Third, Puerto Rico is a “price taker” in the global oil and natural gas markets due to the relatively small volume of fuel it buys. And while we don’t doubt the negotiating acumen of NFE’s traders, there are limits to how much savings can be generated from obtaining “better risk credit and credit terms”. Even NFE’s most perspicacious traders are subject to the capricious ebbs and flows of the global oil and natural gas markets.

In this context, it is relevant to point out that Section 9.2(b) of the Generation O&M Agreement politely prohibits Genera, NFE, and their affiliates from engaging in business with any person located, organized, or resident in a Sanctioned Country, which is defined in Section 20.2(g)(iv) of the Generation O&M Agreement as “the Crimea (sic), Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria.” We note, though, that Russia is conspicuously absent from this list. This omission, we assume, is probably nothing more than just a harmless drafting lapse that obviously will be remedied by counsel in due course.

Fourth, Genera insists on pointing to potential savings to be extracted from the conversion of existing oil-burning plants to facilities that burn natural gas. In fact, according to the FTI report, such conversions would generate approximately 50% of total expected savings from the Generation O&M Agreement. Genera and FTI, however, are silent as to who would pay for the capital expenditures necessary to convert existing oil-burning units to burn natural gas.

To be sure, pursuant to Section 5.6(b) of the Generation O&M Agreement Genera may “propose to PREB certain capital improvements, taking into account the Integrated Resource Plan and the Federally Funded Generation Project Plan, that would be (x) federally funded and owned by Owner, (y) made, owned and funded by Owner or (z) made, owned and funded by Operator or its designated Affiliate.” However, Genera and FTI fail to disclose, in the case of capital improvements not financed by the federal government, (i) how the profile of expected savings is affected once the expected cost of capital is taken into account and (ii) how the expected useful life of a legacy asset converted to burn natural gas would be extended in order to amortize the capital expenditure over time — an extension that, presumably, would be in contravention of the stated objective of decommissioning most of the Legacy Generation Assets as soon as possible.

Furthermore, Genera, as we stated above, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of NFE, which is a “full service” natural gas company that operates along the entire supply chain, from procurement, to shipping, to the development of natural gas-fired power generation. This presents at least two conflicts of interest.

First, it would be only natural for Genera to seek to do business with its parent company or its affiliates and there will be pressure to accept whatever terms are imposed by the “friends of the house.”

To be fair, the Generation O&M Agreement sets forth in Annex VI a fully developed policy to address organizational conflicts of interest arising from or in connection with affiliate or related-party transactions, including the requirement to hire a third party to execute the procurement process in certain cases (yet more evidence that governments do learn). It remains to be seen, though, whether this process will be thoroughly and consistently implemented and enforced throughout the term of the Generation O&M Agreement.

The other conflict arises from the fact that Fuel Cost Savings Initiatives is defined in the Generation O&M Agreement to mean any initiatives undertaken by the Operator, its Affiliates or Subcontractors in connection with the Generation O&M Agreement, that reduce Fuel Costs, including by:

- improving the fuel efficiency of any Legacy Generation Assets;

- converting any Legacy Generation Assets to be able to operate on any new alternative fuel(s) (including natural gas and hydrogen);

- supplementing Legacy Generation Assets with power generation equipment at or in the vicinity of the relevant Generation Site that is more fuel efficient and/or operates on any new alternative fuel(s) (including natural gas and hydrogen);

- reducing transportation, testing, delivery or storage (including tank maintenance) costs; or

- pursuing savings opportunities related to credit and portfolio optimization, in each case whether such initiatives are implemented as Pass-Through Expenditures, at the Operator’s cost as the Operator’s own capital improvements pursuant to Section 5.6(b), by replacement or renegotiation of Fuel Contracts or Facility Contracts, or otherwise.

This definition poses several problems. First, it clearly allows the conversion of oil burning units to burn natural gas as a cost-saving initiative (subject to PREB approval), which would be contrary to the stated public policy goal of fully transitioning to renewable fuels by 2050.

Second, by allowing the switch to natural gas as a fuel cost saving measure, the Generation O&M Agreement confronts Genera with a set of potentially incompatible incentives. On one hand, Genera gets to keep 50% of any fuel savings generated by its implementation of any Fuel Cost Savings Initiative. On the other hand, Genera keeps 50% of any savings it generates when the process for decommissioning a legacy asset ends up costing less than originally budgeted.

In most, if not all instances, the amount of money represented by the right to get paid 50% of any realized fuel cost savings will exceed the amount of money represented by the right to get paid 50% of the savings generated from successfully decommissioning a legacy asset 10 or 15% under budget. Thus, Genera probably will have a strong preference for projects that switch generation units to burning natural gas, especially if the fuel is provided by NFE or any of its affiliates , and against decommissioning assets that could be converted to burn natural gas. It will be up to the P3 Authority and the PREB to prevent this risk from becoming a reality.

Third, the definition of Fuel Cost Savings Initiatives also includes any savings generated by switching to the burning of hydrogen. Now, this is interesting because NFE stated in its annual report for the year ended December 31, 2021 “that low-cost hydrogen will play an increasingly significant role as a carbon-free fuel to support renewables and displace fossil fuels across power, transportation and industrial markets.”

To that end, NFE has formed a new division, which it calls Zero, “to evaluate promising technologies and pursue initiatives that will position us to capitalize on this emerging industry.” In addition, it has signed an agreement “to transition a power plant to be capable of burning 100% green hydrogen over the next decade”, and it has made its “first hydrogen-related investment in H2Pro, an Israel-based company developing a novel, efficient, and low-cost green hydrogen production technology.”[29]

Source: Michael Kobina and Stephanie Gil, Green Hydrogen: A key investment for the energy transition, World Bank Blogs, June 23, 2022

However, true green hydrogen production, which consists of using renewably generated electricity to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen (see chart above), is not yet a commercially viable technology. Most of the current hydrogen production in the world consists of so-called “gray hydrogen”, which is produced by splitting natural gas into carbon dioxide and hydrogen. This process is energy intensive and emits a significant amount of CO2. “Blue” hydrogen is sometimes presented as an alternative. The process for making blue hydrogen is the same as the one for making gray hydrogen, with the difference that the resultant CO2 is “captured” and stored underground and thus is not released into the atmosphere. Most environmental groups, however, are skeptical about the alleged benefits of producing gray or blue hydrogen.

The risk for Puerto Rico here is twofold. First, we have to be vigilant that the island is not used once again as a “laboratory” for testing some half-baked harebrained idea, the brainchild of some demented trafficker of high-tech scams out on the prowl to make a quick buck in the crumbling colonial backwaters of the American Empire, and which imposes high costs and produces little or no benefits for Puerto Rico’s residents — as has happened so often in our history.[30]

And, second, if the production of green hydrogen eventually becomes commercially feasible, we have to ensure that both the technology and the know-how is transferred to Puerto Rican firms and engineers so the island does not end depending yet again on a resource we do not produce and do not control to generate our energy.

Finally, even if it is true that the implementation of the Generation O&M Agreement generates savings of $200 million per year and half of that amount is passed on to Puerto Rican ratepayers, is that amount “significant”? According to an unaudited financial report prepared by PREPA’s management for its governing board, it spent approximately $2.1 billion on fuel during fiscal year 2022, while total expenses for that year added up to $4 billion.[31] Therefore, savings of $100 million are equivalent to 4.7% of fuel expense and 2.5% of total expenses for that period.

Those savings are worth something but they do not by any means represent a paradigm-shattering change. To put this issue in perspective, the amount of expected savings ($100 million) probably will not be enough to fully offset the debt service on PREPA’s restructured bonds, which is estimated will be around $300 million per year, depending on the details of the final deal to be entered into with bondholders under the aegis of the Title III court.[32]

The objective truth is that Puerto Rico’s electricity costs will not decrease significantly until most of PREPA’s Legacy Generation Assets are decommissioned and replaced with new generation capacity using renewable sources. According to PREPA’s Certified Fiscal Plan for Fiscal Year 2022 generation “expenses are projected to decline over the Certified Fiscal Plan period as PREPA-owned generation units are retired, and the mix shifts to third-party owned generation, specifically renewable generation, which will be contracted through PPAs”.[33] Interestingly, neither the P3 Report nor the FTI Report provide an estimate of those savings.

Numerous factors have contributed to delaying the transition to and deployment of renewable generation in Puerto Rico: PREPA’s bankruptcy; lack of access to capital; federal and state bureaucratic requirements; the loss of state capacity to perform complex tasks due to years of austerity policies; the political influence of groups with fossil fuel interests; disagreements among advocates for renewable power who favor building utility-scale capacity and those who propose rooftop-based solar systems (we need both); and a general lack of coordination among and between government agencies, private sector stakeholders, local and community leaders, representatives of NGOs, and other non-profit entities which promote their own projects in a zero-sum fashion.

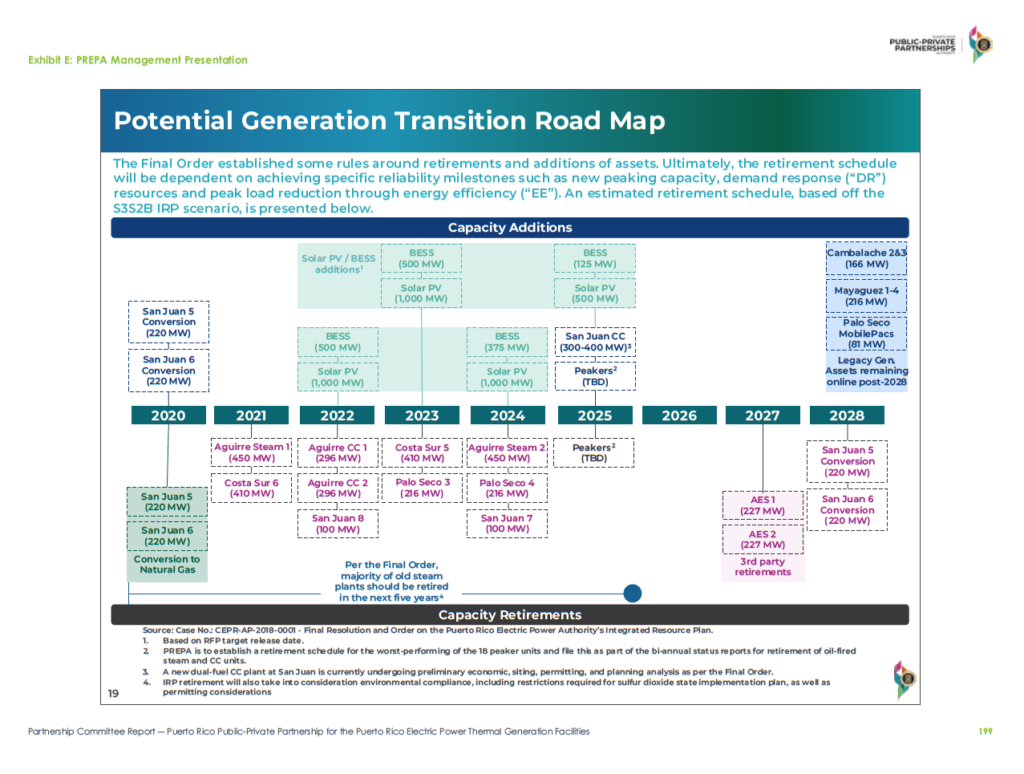

To be fair, we should not underestimate the difficulty and complexity of decommissioning fossil fuel generation while simultaneously deploying large scale renewable generation. As shown in the chart below, which is from PREPA’s Management Presentation to participants in the RFP process for awarding the Generation O&M Agreement, the scale of the transition to renewable generation is enormous. And while the timeline needs to be updated, it does makes us wonder whether the government of Puerto Rico has the requisite state capacity to execute this mega-project on time, on budget, and delivering the estimated benefits.

Source: Exhibit E to the P3 Report, p. 19.

Finally, we note that this “potential transition road map” prepared by PREPA includes the addition of up to 400 MW of new combined cycle capacity using natural gas in the San Juan plant, presumably to be paid by the federal government, and forecasts the continued used of legacy assets in Cambalache, Mayaguez, and Palo Seco beyond 2028.

Market Structure

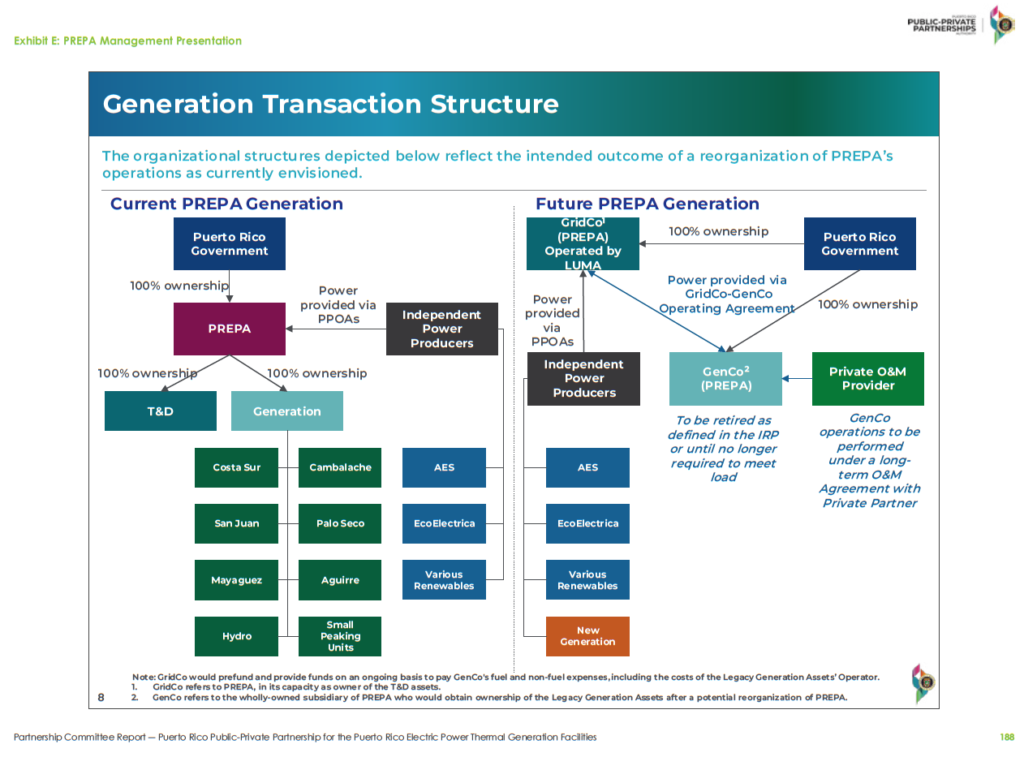

Act 17-2019 calls for “transitioning from the current, vertically integrated monopoly comprising PREPA, to an energy system with multiple players as well as changes to the roles and responsibilities that have historically been concentrated within PREPA, and their reallocation across multiple entities.” According to that Act, one of the objectives of unbundling PREPA’s vertically integrated monopoly is to introduce an element of competition into Puerto Rico’s electricity market. To that end, according to the P3 Report, the Legacy Generation Assets Project is “intended to ‘promote market competition’ by harnessing private sector creativity and resources to help fully deliver on economic, infrastructure, and societal goals identified by the Government.”[34]

At first glance it appears that the execution of the T&D O&M Agreement and the Generation O&M Agreement satisfies the basic requirements of Act 17. While PREPA retains the naked title to the transmission and distribution system and to the legacy generation assets (for purposes of qualifying for federal funding), their respective day to day operation and management have been unbundled and legally transferred to two private operators.

Source: Exhibit E to the P3 Report, p. 8.

However, a closer look at the structure of Puerto Rico’s electric power market after the execution of the T&D and the Generation agreement makes us wonder whether it achieves the policy objectives set forth in Act 17.

First, as shown in the chart above, after the Service Commencement Date of the Generation O&M Agreement, Puerto Rico would have an oligopoly of utility-scale generation companies: Genera, AES, EcoEléctrica, various renewable generators, and whatever new renewable generation is eventually deployed. On oligopoly can be defined as “an economic condition where only a few companies sell substantially similar or standardized products” and “oligopoly markets often exhibit the lack of competition, high prices and low output of monopoly markets.”[35]In oligopolistic markets, prices tend to be set by the firm with the largest market share. In the instant case, the generation market in Puerto Rico will be dominated, at least during the next five years, by Genera which will be operating the most inefficient, and hence the most costly, generation fleet in the island. Thus, we can expect the transfer of the operation and management of PREPA’s generation assets to have only a marginal, if any, effect on prices and reliability, at least in the medium-term.

Second, those oligopoly producers can sell their product (electricity) only to LUMA. Therefore, LUMA will have a monopsony with respect to independent power producers in Puerto Rico. A monopsony can be defined as “a market condition in which there is but one buyer for a particular commodity.”[36]Monopsonies can result in lower wages for workers, lower quality products, and higher prices for the consumer. Now, LUMA would probably argue that these risks are mitigated because they are required to buy power from independent power producers that have long-standing power purchase agreements (“PPAs”) with PREPA, in the case of AES and EcoElectrica, or that will be negotiated in the future, in the case of new entrants to the market. In any event, LUMA would argue, everything is subject to regulation by the PREB. That is true up to a point and good as far as it goes, but the situation could still lead to any number of market failures. For example, if a corporate affiliate of LUMA or Genera, or of their respective parent companies, wins the bid to build and operate the new combined cycle units (up to 400 MW) that will be located in the San Juan plant, what’s to stop LUMA or Genera from granting priority to their affiliate in connecting and dispatching electricity to T&D System?

Third, to complicate matters even further, LUMA has a monopoly on the other side of the market, namely the sale of electricity to retail, commercial, and industrial clients. Consumers in Puerto Rico can only buy electricity from LUMA, unless they set up their own generation capacity (in which case they can sell any excess generation, if they have net metering capabilities, only to LUMA).

While it is true that Puerto Rico has developed regulations to allow “wheeling” (the direct sale of excess electricity generated by say a manufacturing firm with in-house industrial scale generation to another industrial client), to our knowledge there has been little no wheeling sales executed in Puerto Rico. A single company, therefore, exercises de facto control of both sides of the electricity market in Puerto Rico: generators can sell and buyers can buy electricity only from LUMA. We question whether that result was intended by the drafters of Act 17.

Given this complicated market structure, any element of market competition will be promoted only indirectly if and when the time comes to renegotiate existing, or to negotiate any prospective, power purchase agreements between LUMA and independent power producers. We note that neither the P3 Report nor the FTI Report analyze whether competition prompted by the new market structure for the electricity sector in Puerto Rico would generate lower prices for ratepayers in the island.

In sum, the resulting market structure is fertile ground for any number of anticompetitive practices, such as collusion, price fixing, exclusive dealing, and price discrimination, among others, to arise. To prevent LUMA from unduly exercising its market power it will be necessary (1) to closely supervise the implementation of the T&D O&M Agreement; (2) for the PREB to conduct robust regulatory oversight of LUMA; (3) to establish a well-regulated and orderly wheeling market in Puerto Rico; and (4) to consider creating an independent system operator that would be in charge of managing the economic dispatch of generation units and supervising interconnections with the T&D System.

Buy Local Provisions

A novel feature (for Puerto Rico) of the Generation O&M Agreement is that it requires Genera to use “commercially reasonable” efforts to ensure that local companies, or foreign companies with a significant presence in Puerto Rico, are included in the procurement process for materials and services under the agreement.[37] In addition, the Generation O&M Agreement requires Genera to use “commercially reasonable” efforts to select companies established under the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico or companies that have “a significant presence in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico” as material subcontractors.[38] These provisions, if implemented, have the potential to generate local economic activity and allow local firms and workers to obtain valuable experience working on a complex multi-year project.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s words to the effect that “the web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together”, are perhaps an apt description of the Generation O&M Agreement.[39]

Several elements of the new agreement are clearly superior to the LUMA T&D O&M Agreement. Among these we can mention a well-developed system of incentives and penalties to motivate the Operator; the inclusion of clear benchmarks to measure Genera’s performance; stronger filters to analyze transactions with affiliates and related-parties, including a fully fleshed-out policy to address organizational conflicts of interest; the requirement to engage in good faith negotiations with current PREPA employees so as to minimize the learning curve of the new operator; and setting a cap on the fees that the Operator can earn during the Mobilization Period; all point to the conclusion that this is an agreement that offers better protections to the people of Puerto Rico from some of the foreseeable risks associated with this transaction.

Other aspects of the agreement are not as good. For example, most of the services will be provided by subcontractors (wouldn’t it be more efficient just to contract directly with them?); the analysis of the expected savings is clearly deficient and we would like to see a more rigorous examination of those professed savings; and it is not clear to us that the resultant market structure will lead to lower prices, generate allocative efficiencies, and/or produce significant increases in consumer welfare.

So, relative to the status quo, is the post-Genera electricity market in better shape in Puerto Rico? Probably yes, but that is an awfully low bar. Everybody who has objectively analyzed PREPA’s performance over the last 30 or 40 years has concluded that it is mess, the financial and operational equivalent of a long-smoldering dumpster fire. By that standard, trying anything new, no matter how outlandish it may seem, would probably constitute progress.

However, if we set a higher bar, if we ask whether this transaction will really help Puerto Rico achieve its long-standing goals of generating affordable, cleaner, and reliable electricity, then the answer is not quite as clear, for the good is indeed mingled with the ill. The fact is that there is a lot uncertainty surrounding this transaction and it is hard to avoid the unsettling feeling we are being presented with a fait-accompli on a take it or leave it basis.

Maintaining the status quo, though, is not an option. The real question is whether there is a better alternative to a negotiated agreement in this instance. The answer, when taking into account the totality of the circumstances, appears to be no. The available alternatives seem to be (1) worse, for example, resuscitating PREPA; (2) unrealistic, entailing, for instance, the creation of a new Tennessee Valley Authority-like entity to provide electricity in Puerto Rico; or (3) downright utopian, involving extremist schemes reminiscent of Mao’s Great Leap Forward.[40]

After assessing the risks and benefits of the Generation O&M Agreement we face a dilemma in the classical sense of making a decision with no good options. But in a situation with no objectively good options, taking a calculated risk may, perhaps, be the best option. Again, in the words of the Bard of Avon: “there is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries. On such a full sea are we now afloat, and we must take the current when it serves, or lose our ventures.”[41]

Endnotes

[1] Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnerships Authority, Partnership Committee Report regarding the Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnership for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Thermal Generation Facilities, October 17, 2022, amended January 18, 2023 (the “P3 Report”), p. 16.

[2] P3 Report, p. 17-18.

[3] P3 Report, p. 18.

[4] P3 Report, p. 19.

[5]See Beatriz de la Torre, “AEE pasa con fichas”, El Vocero, 21 de marzo de 2013; “Nebuloso financiamiento de ‘mareducto’”, El Vocero, 23 de mayo de 2013; and “Denuncian ‘chanchullo’ en AEE”, El Vocero, 22 de julio de 2013; and Mary Williams Walsh, “At Puerto Rico’s Power Company, A Recipe for Toxic Air, and Debt”, New York Times, February 15, 2016; and “In Scandal at Puerto Rico Utility, Ex-Fuel Buyer Insists He Took No Bribes”, New York Times, March 2, 2016.

[6] New Fortress Energy, Inc., Annual Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2021, filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission on Form 10-K, p. 3.

[7] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 4.1(a).

[8] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 4.2(u).

[9] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 4.6(b).

[10] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 4.8(a).

[11] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 5.1.

[12] Section 1.A. of Annex IX to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[13] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 7.7(a).

[14] Section 1.A. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[15] Section III.B of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[16] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 5.22.

[17] Section III.B.2. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[18] Section III.B.5. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[19] Section III.B.6.(a) of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[20] Section III.B.6.(c) of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[21] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 16.1(a).

[22] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 16.1(b).

[23] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 16.2(d).

[24] Section III.C.1. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[25] Section III.C.1. of Annex II to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[26] Section 1 of Annex XVI to the Generation O&M Agreement.

[27] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 17.3(b).

[28] FTI Consulting, Benefits of a Third-Party Generation Operator of the Puerto Rico Legacy Generation Assets, September 22, 2022, p. 18-19, included as Exhibit B to the Partnership Committee Report regarding the Puerto Rico Public-Private Partnership for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Thermal Generation Facilities, October 17, 2022, amended January 18, 2023.

[29] New Fortress Energy, Inc, Annual Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2021, filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission on Form 10-K, p. 16.

[30] See Juan R. Torruella, “Why Puerto Rico Does Not Need Further Experimentation with its Future: A Reply to the Notion of Territorial Federalism”, Harvard Law Review Forum, Vol. 131, No. 3, (January, 2018).

[31] Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, Monthly Report to the Governing Board: June 2022, p. 7, available at https://aeepr.com/es-pr/investors/FinancialInformation/Monthly%20Reports/2022/June%202022.pdf

[32] Assuming PREPA’s bonded debt is cut approximately by 50% to $5 billion and a 6% coupon.

[33] 2022 Certified Fiscal Plan for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority As certified by the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico on June 28, 2022, p. 164.

[34] P3 Report, p. 29.

[35] Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, (St. Paul, MN; West Publishing Co., 1990), p. 1086.

[36] Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, (St. Paul, MN; West Publishing Co., 1990), p. 1007.

[37] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 21.19(c).

[38] Generation O&M Agreement, Section 21.19 (d).

[39] William Shakespeare, All’s Well that Ends Well, Act IV, Sc. 3, (1603-1604).

[40] Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History, (London: The Bodley Head, 2019), pp. 133-168.

[41] William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act IV, Sc. 2 (1599).