Published on May 22, 2020 / Leer en español

Note from the editor

Dear readers:

During the past two months it has been my privilege, with the extraordinary help of CNE’s hardworking team, to bring this daily briefing to you. We hope you have found it useful and informative during these challenging times.

Now as Puerto Rico and the mainland start opening up their economies and lifting certain restrictions in a cautious attempt to restore some sense of normality, we will also evolve from publishing a daily briefing to a weekly layout. The idea is to focus less on the day-to-day headlines and provide additional in-depth analysis from CNE’s team of experts, but still in a highly readable and accessible format.

In addition, we will concentrate our attention on some of the important economic, social, and political questions that will inevitably arise in this new world where we are being called to co-exist with a highly transmissible virus, that has proved lethal and about which we still don’t know nearly enough.

We invite you to accompany us in this new venture, beginning next Thursday, May 28. Until then, thank you for your support, stay healthy, and keep safe.

Sergio M. Marxuach

Five things you should know today

1) Summer weather could help, but won’t end the pandemic

Recent studies lend support to the theory that summer heat, humidity, and sunshine could slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus. According to the Washington Post a new working paper published “by researchers at Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other institutions” found that:

- Average temperatures above 77 degrees are associated with a reduction in the virus’s transmission;

- Each additional 1.8-degree temperature increase above that level was associated with an additional 3.1 percent reduction in the virus’s reproduction number, called R0;

- In general, higher levels of relative humidity strengthen the negative effect of temperature above 77 degrees;

- One millibar of additional pressure increases R by approximately 0.8 percent (0.6-1%) at the median pressure (1016 millibars);

- There are also significant positive effects for wind speed, precipitation, and diurnal temperature on R; and

- The “results provide evidence for the relationship between several weather variables and the spread of COVID-19, finding a negative association between temperature and humidity and transmission.”

The authors warn, however, that “the (conservatively) estimated effects of summer weather are not strong enough to seasonally control the epidemic in most locations.” This conclusion is supported by another new study, from researchers at Princeton University and the National Institutes of Health, which “found that our lack of immunity to the coronavirus will overwhelm any tempering influence that warm, humid weather may have on the virus’s spread”.

It appears, then, that summer weather by itself will not be enough to control the spread of the virus. Hence, the CDC recommends that people keep practicing social distancing and wearing masks even if outdoors. Finally, it is important to remember that “seasonal factors in virus transmission work the other way around, too: A decline in transmission in summer would probably be followed by a seasonal increase in infections in the fall.”

2) The virus spreads in different ways, complicating mitigation efforts

Ed Yong, writing for The Atlantic, finds that the virus is spreading “through different parts of the U.S. in different ways, making the crisis hard to predict, control, or understand.” The national infection curve tells one story, while each state’s curve tells a different one. In New York and New Jersey the disease is declining; in Oregon and South Carolina it is stable; while in Texas and North Carolina it is taking off. This is what he calls the “patchwork pandemic.”

Furthermore, “the patchwork is not static. Next month’s hot spots will not be the same as last month’s. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is already moving from the big coastal cities where it first made its mark into rural heartland areas that had previously gone unscathed.”

The fractured pattern complicates policymaking because “cities that thought the worst had passed may be hit anew. States that had lucky escapes may find themselves less lucky.” Moreover, “the future is uncertain, [and] Americans should expect neither a swift return to normalcy nor a unified national experience, with an initial spring wave, a summer lull, and a fall resurgence.”

In sum, getting over the pandemic will be difficult because many factors shape the pandemic and the disease progresses slowly and unevenly.

3) The natural experiment

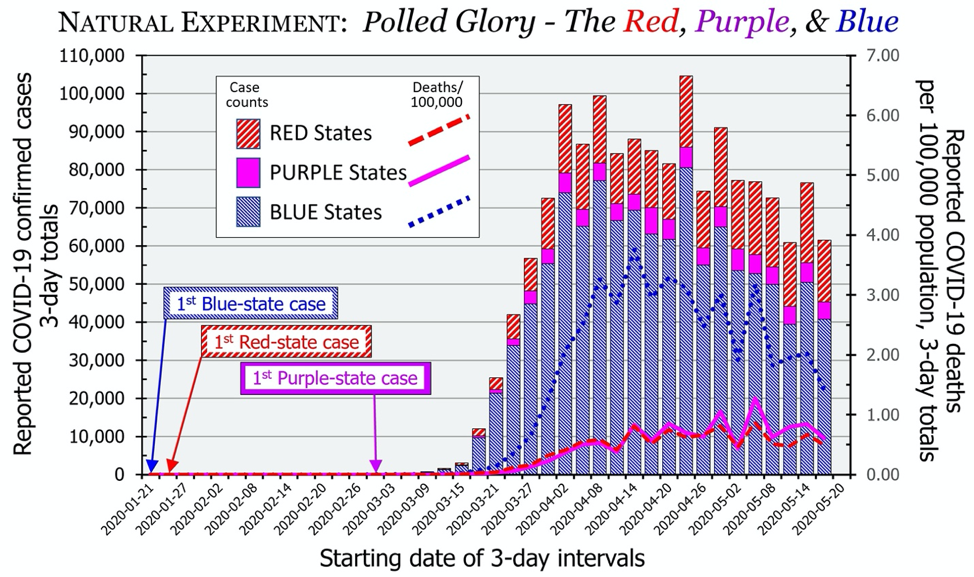

Ed Yong’s thesis is supported by evidence marshaled by Dr. Bruce Weniger and Dr. Chin-Yi Ou, both retired scientists from the CDC. In a fascinating piece published in Medium, they argue that the U.S. is “entering what epidemiologists call a natural experiment.”

In this “unblinded natural experiment, the states and regional consortia of them are determining the onset, pace, and degree of their relaxations. Then experts will compare the illness and death that follow, taking into account as well the extent they achieve in testing, case isolation, and contact quarantine.”

The authors’ “admittedly crude approximation to observe the effect of ‘opening up’ is to stratify by political preferences: red, purple, and blue.”

As shown in the chart above, they find that “densely-populated areas, mostly ‘blue’, were seeded early by imported virus and hit hard. Urban transportation systems with crowded buses and trains likely facilitated transmission. Nevertheless, comprehensive lockdowns put them onto downslopes of their curves. But the epidemic continues to spread inexorably in rural areas, mostly ‘red’ states, with more dispersed populations, different commuting means (car and pickup), and other features that may slow but not eliminate transmission.”

The authors conclude with a harsh warning: “The resulting state and national epidemic curves will be as volatile as the recent stock market. Governors who ‘open up’ their states too soon or too broadly may turn out to be Pied Pipers leading some constituents into the folkloric river to drown.”

4) The problem of scale

Scientists are increasingly hopeful they will be able to develop an effective vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus within 12 to 18 months, which is unheard of in this field. However, manufacturing and distributing it to the world could be a problem. As explained in this piece in the New York Times, “vaccines typically require large vats in which their ingredients are grown, and these have to be maintained in sterile conditions. Also, no factories have ever churned out millions of doses of approved vaccines made with the cutting-edge technology being tested by companies like Inovio and Moderna.”

Manufacturers do have significant experience “mass-producing inactivated vaccines, made with killed viruses, so this type may be the easiest to produce in large quantities.” But as many experts have warned there will be a need for more than one type of vaccine, because “if that were to happen, the company that made it would have no chance of meeting the world’s demand.”

In addition, let’s not forget about all the ancillary items that are needed for a mass vaccination campaign. In the words of Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, “It’s the little things like the syringes, the needles, the glass vials. All of that has to be thought about. You don’t want something that seems so simple to be the bottleneck in your vaccination program.”

Finally, there is the issue of affordability. There is no vaccine yet, but already there are questions of who will be able to pay for it. The European Union has suggested creating a voluntary patent pool putting pressure on companies to give up monopoly profits on the vaccines they develop. Other world leaders have called for the vaccine to be declared a public good. Which would be fair given the large amount of public money currently financing research and testing for this vaccine. In the end, though, the most compelling reason is that “we’re not safe till everyone is safe”, in the words of Helen Clark, former prime minister of New Zealand.

5) Some Republican senators start feeling the heat

With elections less than six months away, some Republican senators are starting to have second thoughts about Senator Mitch McConnell’s “pause” on any new legislation providing additional economic assistance in connection with the COVID-19 crisis. According to The Hill “a growing group of GOP senators, which includes some of the conference’s most vulnerable members in this year’s elections, say they shouldn’t let another month pass without significant progress on another economic relief package.”

Among those who have expressed their support for moving legislation as fast as possible are Senator Susan Collins (R-Maine) who “took to the floor Wednesday to urge her colleagues not to wait any longer on passing another relief package with hundreds of billions of dollars in additional aid to state and local governments” and Senator Cory Gardner (R-Colorado) who “urged the Senate not to leave town for the weeklong Memorial Day recess after making little to no progress on another coronavirus relief bill.”

We do not know if these senators are willing to break ranks with Senator McConnell, who is known for running a tight ship. But the pressure for re-election, combined with some cover provided by Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Reserve, could be sufficient to nudge these senators to cut a deal with the Democrats. We will keep you informed as events develop.

Quote of the Day

“For the most part [town officials] were men with well-defined and sound ideas on everything concerning exports, banking, the fruit or wine trade; men of proved ability in handling problems relating to insurance, the interpretation of ill-drawn contracts, and the like; of high qualifications and evident good intentions. That, in fact, was what struck one the most — the excellence of their intentions. But as regards the plague, their competence was practically nil.”

—Albert Camus, The Plague

This is the end of our daily briefing.

Stay safe and well informed!