I do not envy the people responsible for making the five-year economic projections for the Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority (“AAFAF”) and the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico (“FOMB”). Given the current level of uncertainty, performing this exercise with a minimum degree of precision is basically impossible. Furthermore, there is no macroeconomic model that can accurately estimate the economic impact of the concatenation of recent events: the bankruptcy of the government, the 2017 hurricanes, the earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic; or forecast the effects of these events five years out when the effects of each one can intensify or weaken the effects caused by the others, there are too many connections and interrelationships between the variables. But human beings like to pretend that the more knowledge we have, the more we can control the future. That is an illusion, of course, as Mark Lilla, professor of Political Science at Columbia University, warns us, because “in fact we are always just tapping our canes on the pavement in the fog.”

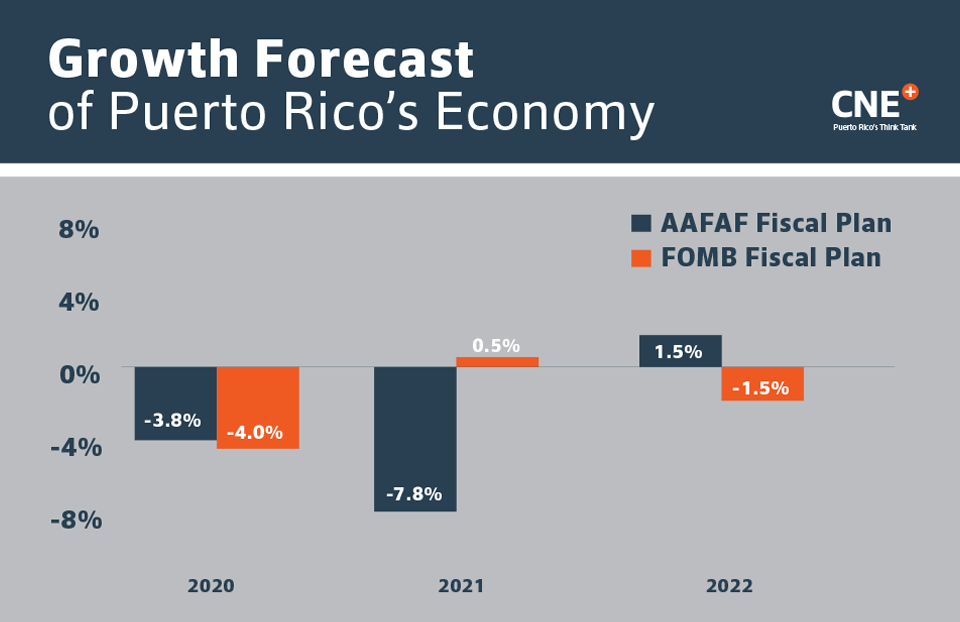

PROMESA, however, requires that a five-year fiscal plan be prepared, not only to serve as the basis for the annual budget, but also to prepare the Plan of Adjustment to be negotiated with creditors. So we go out to the streets and tap with our canes, to see what we find. The AAFAF economic team estimates that the economy will contract by 3.6% and 7.8% during fiscal years 2020 and 2021 and will rebound in 2022 with growth of 1.5%. While the FOMB experts forecast a contraction of 4% in 2020, a modest bounce back of 0.5% in 2021 and a contraction of 1.5% in 2022.

Both the AAFAF and the FOMB plans are based on three main elements: (1) fiscal consolidation (increased revenues and cuts to government spending); (2) the implementation of structural reforms; and (3) a large flow of transfers from the federal government. But it appears that the AAFAF has a more conservative view of economic activity over the next two fiscal years. While the FOMB seems to bet on a faster economic recovery due to the impact of the structural reforms it proposes to be implemented in an accelerated manner. Perhaps for the next iteration of the Fiscal Plan it would be more useful to include a probabilistic range of economic projections that indicates, for example, that there is “a 95% probability that the growth rate will be between x% and z%.”

The underlying problem, however, is that today we do not have a methodology that allows us to choose in an informed way, that is, not based on our ideology or personal preference, between the optimistic and pessimistic scenario. We are in a situation similar to that of the famous “thought experiment” designed by the physicist Erwin Schrödinger. In layman’s terms, if a cat and something that could kill it (a radioactive substance) were placed in a box and sealed, whether the cat is alive or dead is not known until the box is opened, so until that time, the cat is (in a sense) “alive and dead” at the same time.

This is not a mere academic exercise. The certified Fiscal Plan will have repercussions in everyone’s life. For example, although the FOMB postpones fiscal consolidation for one year (correctly in our opinion), the Plan proposes an increase in collections of $2.2 billion and spending cuts of $6.2 billion during the next five fiscal years (Exhibits 137 and 138). That $8.4 billion fiscal contraction is equivalent to 11.8% of GNP as of June 30, 2019, a high dose of austerity, even without taking into account the negative multiplier effect on the economy. We must also ask ourselves if this contractionary fiscal posture is adequate, when the FOMB itself estimates that the unemployment rate will remain in excess of 15% until at least June 2021 (Exhibit 7).

In terms of debt repayment, the FOMB estimates that the surplus available to bondholders will be reduced considerably due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This should not surprise us given all that has happened. But beyond determining a “surplus” amount for payment to bondholders, the important question to ask ourselves is whether the government of Puerto Rico is currently in a position to commit in good faith to pay x million annually for servicing a restructured debt for 30 years — given the margin of error in economic and financial projections. I think the answer is no.

Now, extending the bankruptcy process for an additional two to three years is also not an option. The longer it takes for Puerto Rico to emerge from bankruptcy, the more difficult it will be to attract the investment necessary to restore long-term growth.

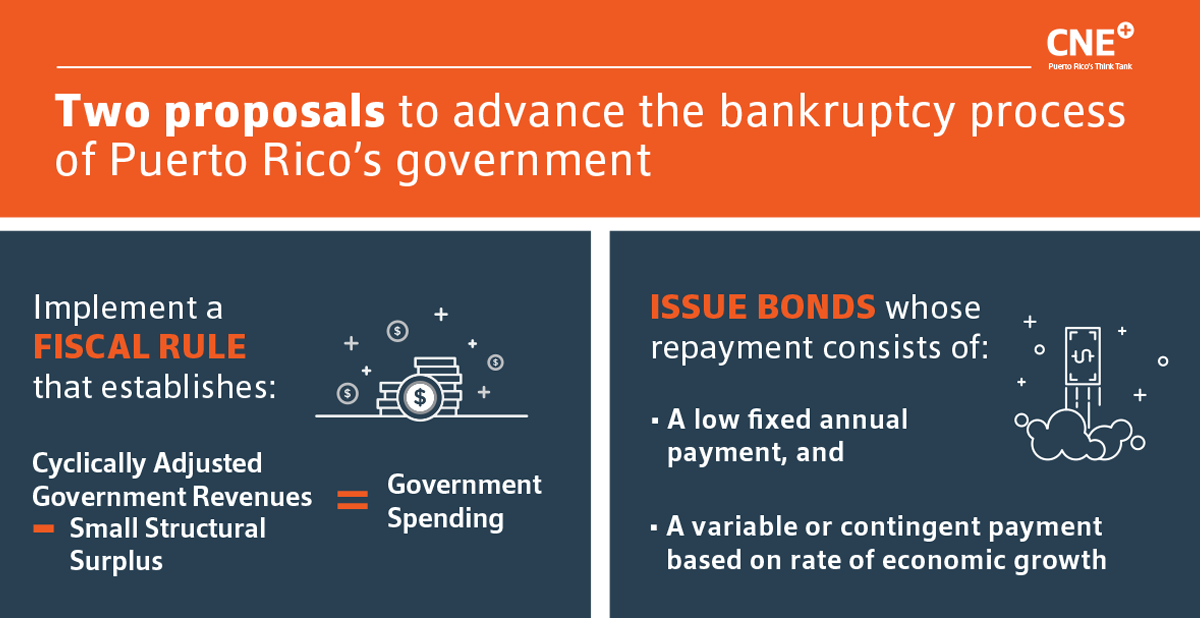

That is why we make two public policy proposals to advance the process even with the great uncertainty that exists.

The first is the implementation of a fiscal rule for Puerto Rico, as we proposed in 2016. A robust and well-designed fiscal rule establishes a clear and easy to verify numerical objective for public spending, taking into account the cyclical nature of government revenues, and provides for the long-term sustainability of the public debt. Therefore, we propose the following fiscal rule for Puerto Rico: annual general fund spending shall not exceed (1) cyclically adjusted government revenue, as determined by an independent panel of professional economists and other experts in fiscal policy, minus (2) a small structural surplus.

Implementing this type of tax rule has several advantages. First, government spending, by definition, would be limited to its structural income, less the amount of the surplus deemed appropriate. Therefore, government spending would be independent of short-term fluctuations in income caused by cyclical variations in economic activity.

Second, it allows the implementation of a moderately counter-cyclical fiscal policy: the government saves when it has the capacity and spends in excess of its annual income when it is in need. Massive increases in spending when the economy is buoyant and drastic reductions in spending when the economy goes into recession are eliminated.

Third, the structural surplus could also be used to (1) gradually amortize the public debt or (2) meet contingent obligations that arise in relation to public pensions or the government’s health plan.

Finally, the budget would be structurally balanced throughout the duration of the economic cycle and this type of fiscal rule would force Puerto Rico to substantially improve the methodology used to develop its income estimates.

The second proposal is to issue bonds whose repayment consists of two components (1) a relatively low fixed annual payment and (2) a variable or contingent payment based on the rate of economic growth. This idea is based on the concept of bonds indexed to GDP growth rate developed by the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. In the case of Puerto Rico, it would be appropriate to use the GNP growth rate due to distortions in our national accounts. Furthermore, this would force us to modernize the methodology to calculate economic activity once and for all.

The proposal is that the variable part of the annual payment would fluctuate proportionally, according to a pre-established mathematical formula, with the nominal growth of the GNP. These bonds would help stabilize Puerto Rico’s finances and limit fiscal pressures by reducing debt service in times when economic growth is slow or negative, and would provide fiscal space to increase expenses or reduce taxes—according to the fiscal rule—when GNP grows rapidly. These bonds also have the added benefits of (1) reducing the need to drastically cut welfare programs during recessions and (2) limiting overspending in times of rapid growth.

From the perspective of investors, these bonds are attractive because they provide them with an opportunity to benefit from future growth by offering them what is called “equity-like exposure.” In this sense, the interests of the government and the bondholders align, since both benefit when the economy grows. In addition, by allowing the debt service-to-GNP ratio to drop during times of slow or negative growth, these bonds reduce the likelihood of default and of a future fiscal crisis.

In these times of great uncertainty, a five-year Fiscal Plan does not do much good. And it is not because they are not well prepared, our intention here is not to criticize the AAFAF or the FOMB. Simply put, events will make it useless in six months. It is also not feasible to make a fixed payment offer to bondholders in good faith for the next thirty years, knowing that we will probably not be able to comply with the terms and conditions of the restructured bonds.

On the other hand, the Title III process cannot be prolonged indefinitely, since that would also negatively affect economic growth. Therefore, it is necessary to seek creative solutions that help us reduce uncertainty, balance the budget, comply with the terms of the restructured central government debt, and grow the economy in a sustainable way. A well-designed fiscal rule and GNP-indexed bonds meet those criteria. Two proposals that would help us move from the current situation, albeit gradually, “tapping our canes on the pavement” as we move forward.

An edited Spanish-language version of this column was originally published on June 7, 2020 in El Nuevo Día.