Published on September 17, 2020 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

There are less than seven weeks left before Election Day. An appropriate time, we think, to take a look at cutting-edge or innovative economic policy ideas. A good time also to pose interesting questions about some of the many issues affecting Puerto Rico, such as economic stagnation, the post-Maria reconstruction process, and the roles of the government and the private sector as they relate to economic development.

Today we begin our seven-week series, FOCUS 2020, dedicated to those subjects. First in line is a brief historical background that will frame the discussion to follow over the next few weeks. Puerto Rico’s economic troubles did not start with the debt default in 2015. In fact, it could be argued that the default was essentially a function of a long-stagnant economy. So it is necessary to understand the policy successes and failures of the last few decades before we plunge into the world of new policy ideas.

We hope you find this discussion interesting and thought-provoking as we approach the November general election.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Part 1 – How did we get here?

In this week’s installment, we delve into the roots of Puerto Rico’s current economic challenges. Taking it back to 1945 with the arrival of state-owned firms, past the first phase of the “export-led model” in the 50s, to the upgraded federal tax exemption that drove manufacturing from the mid-70s to the early 2000s, we try to answer the question of how Puerto Rico got to be in the worst economic crisis it has seen since the Great Depression.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Brief Economic History of Puerto Rico Since 1945

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

The modern economic history of Puerto Rico begins in the aftermath of the Second World War, perhaps the most destructive conflict in the history of humanity. Europe was in ruins from Normandy to the outskirts of Moscow. The productive capacity of Germany and Japan was decimated. China was about to embark on a civil war. India was still a colony of the soon to be liquidated British Empire. Globalization, understood as the international flow of goods, direct investment, financial capital, and people (with the exception of millions of displaced persons and returning prisoners of war), was at a low point.

Seventy-five years is a long time. Three generations of Puerto Ricans have been born since 1945. But it is important to remember that this de-globalized economy was the context under which Puerto Rico embarked on an ambitious program to modernize its society and change the structure of its primarily rural economy to one dominated by manufacturing.

Initially, the plan was for the Puerto Rican government to directly drive the process by setting up a conglomerate of state-owned firms. This path, however, was quickly discarded after a couple of years and the companies sold to the private sector. It was followed by what was then a relatively novel and ingenious program based on attracting capital from the United States using tax incentives, matching it with Puerto Rico’s surplus labor, and “exporting” the manufactured products back to the United States. Notice, though, this economic strategy was based on advantages that turned out to be temporary or otherwise characteristic of a de-globalized world, namely the lack of other outlets for U.S. capital, the availability of cheap labor, and uniquely free access to the U.S. market.

By some accounts, this “export-led” model, with some later re-tooling, was relatively successful. Puerto Rican economic growth rates soared between 1948 and 1974, with an annual average real rate of 6 percent between 1950 and 1975 and comparable growth in output per worker. Living standards increased as well, as measured by most standard indicators: literacy rates and educational attainment; health outcomes and life expectancy; infant mortality; access to clean water, electricity, and safer housing; and persons per physician all improved significantly.

Yet, by other measures, the structural transformation of Puerto Rico’s economy and society fell short of the mark. Rapid job growth in the manufacturing sector did not replace all the jobs lost in the agricultural/traditional sector and total employment in 1960 was lower than in 1950. The apparent contradiction between rapid growth and relatively high unemployment is explained by a very low participation rate and a large reservoir of underutilized labor. Even with strong internal growth, Puerto Rico experienced a massive out-migration. Over 650,000 persons left the island during the period between 1945 and 1964, out of a total population of 2.2 million in 1950.

One response was the construction of a massive petrochemical complex in the southern part of the island, spurred by a presidential Executive Order that exempted Puerto Rico from U.S. crude oil import quotas. The objective was to move to higher-value-added, capital-intensive manufacturing operations that created high-wage jobs and generated forward and backward linkages with, as well as positive spillover effects in, the Puerto Rican economy.

This plan did succeed in bringing some of the largest firms in the petrochemical industry to the island. Yet it suffered from one unalloyed weakness: Puerto Rico’s new industrialization strategy was based on cheap access to a raw material, petroleum, which Puerto Rico did not produce nor control. This weakness became palpably clear with the OPEC embargo following the Yom Kippur War of 1973. In some ways, Puerto Rico has never fully recovered from the first oil shock, which ended Puerto Rico’s petrochemical dreams.

The times called for a thorough questioning of the prevailing economic strategy but the Puerto Rican government, instead of rethinking the existing economic model and restructuring the productive basis of the economy, simply tinkered with it: obtaining a new federal tax exemption for U.S. firms operating in Puerto Rico (Section 936), increasing government employment, seeking additional increases in federal transfers (food stamps, among others), and issuing public debt in ever larger amounts.

This economic “model” would jumpstart growth in Puerto Rico, but not to the levels seen during the 1950s and 60s. Indeed, between 1975 and 2004, the island’s GDP would grow at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent. Yet by the first decade of the 21st century, it became evident that Puerto Rico’s economic model had collapsed. Section 936 had been phased-out by the federal government; government employment had increased to its upper limits; federal transfers are contingent on the economic and political dynamic in Washington D.C.—and thus could not be the basis of future growth—and public indebtedness was then at historic highs.

Furthermore, those advantages that were specific or particular to Puerto Rico in 1945 had either disappeared, in the case of cheap labor, or ceased to be unique to Puerto Rico, in the case of the dollar, privileged access to the U.S. market, and political stability. At the same time, international trade, investment, and financial flows, as well as migratory movements, exploded. The pressing challenge was to think about how Puerto Rico could insert itself in these global flows. Yet, policymakers in Puerto Rico remained either oblivious to, or willfully ignorant of, this new reality.

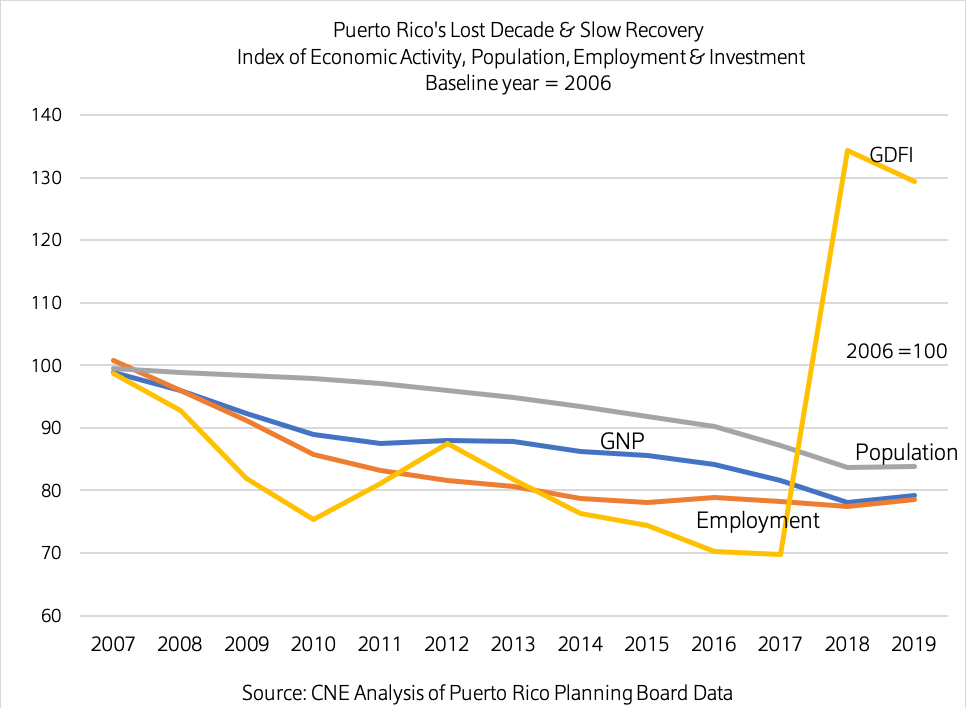

Given this series of unfortunate events, it is unsurprising that in 2006 Puerto Rico’s economy entered a period of sustained decline. As shown in the chart below, real output today is approximately 21% below its 2006 level. Puerto Rico’s government was, understandably, reluctant to cut current expenses – laying off government employees when the private economy was contracting would have left many families without any income, and added to the overall economic woes. But sustaining current spending increasingly required short-changing the pension system and long-term borrowing to cover ongoing budget deficits.

By 2015, Puerto Rico was out of money and out of options. The economy had been in a prolonged secular decline, a depression really, since 2006; net migration to the mainland was increasing, while the natural rate of population growth was decreasing, generating a significant reduction in the island’s population; the government was running chronic budget deficits; tax evasion was widespread, and government corruption proliferated.

At the same time, the island’s government issued ever-growing amounts of public debt just to keep operating. Indeed, between 2000 and 2014 the island’s indebtedness increased at an average rate twice as fast as its GNP. By the summer of 2015, it was obvious that Puerto Rico would not be able to postpone its day of reckoning much longer, it owed $72 billion in bonded debt (exceeding its GNP) and another $50 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. Governor Garcia Padilla acknowledged the obvious and announced to the world that Puerto Rico’s debt was unpayable.

In sum, the Puerto Rican economy was in a deep structural decline prior to declaring bankruptcy and the damage inflicted by the hurricanes, the earthquakes, and the pandemic. And to the best of our knowledge, Puerto Rico is the only jurisdiction to simultaneously go through a debt/fiscal crisis, a reconstruction process after a major natural disaster, and a pandemic. This, dear reader, is the complex background that frames our current economic situation.

CNE Spotlight

CNE’s primary and ultimate goal as Puerto Rico’s think tank has always been to improve the well-being of everyone in our archipelago and to increase opportunities for generations to come. We invite you to visit our website and discover the wealth of research, analyses, and public policy proposals we have carefully crafted during the past 21 years.

This week we want to highlight: CNE’s President, Miguel A. Soto-Class’ remarks about the government’s capacity to administer federal funds and how the institutional collapse will affect Puerto Rico’s opportunities to recover. CNE’s 2013’s most-read column Se acabó la fiesta highlights how we got to the situation we are today. If you want to read about a wider range of major policy issues affecting the island’s economic development, you can read CNE’s The Economy of Puerto Rico: Restoring Growth (2006), a comprehensive economic policy book with analyses of dozens of local and international scholars.

On Our Radar...

![]() “Doing Business” Is Out of Business – On August 27 the World Bank announced it would cease publication of its “Doing Business” report, which it had published since 2003. In its announcement, the World Bank cited “irregularities” with the data as the principal reason for suspending publication. This is worrisome for several reasons. First, as Michael Klein, Professor at SAIS (Johns Hopkins), has stated “method can be debated, data integrity cannot.” If the data used for the Index was flawed or manipulated it is a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Furthermore, we agree with Jayati Ghosh’s, Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, statement that “the Bank also owes the developing world an apology for all the harm this misleading and problematic tool has already caused.” Finally, would someone please tell the Financial Oversight and Management Board that it is using a flawed index to measure the “competitiveness” of Puerto Rico’s economy and perhaps should reconsider its decision to do so?

“Doing Business” Is Out of Business – On August 27 the World Bank announced it would cease publication of its “Doing Business” report, which it had published since 2003. In its announcement, the World Bank cited “irregularities” with the data as the principal reason for suspending publication. This is worrisome for several reasons. First, as Michael Klein, Professor at SAIS (Johns Hopkins), has stated “method can be debated, data integrity cannot.” If the data used for the Index was flawed or manipulated it is a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Furthermore, we agree with Jayati Ghosh’s, Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, statement that “the Bank also owes the developing world an apology for all the harm this misleading and problematic tool has already caused.” Finally, would someone please tell the Financial Oversight and Management Board that it is using a flawed index to measure the “competitiveness” of Puerto Rico’s economy and perhaps should reconsider its decision to do so?

![]() “25 Years Wiped Out in 25 Weeks” – The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation just issued a report which found that “in only half a year, the coronavirus pandemic has wiped out decades of global development in everything from health to the economy.” As reported in Politico, “After 20 years of continuous progress, almost 37 million people have this year become extremely poor, living on less than $1.90 a day, according to the report. ” Furthermore, “‘falling below the poverty line’ is a euphemism, though; what it means is having to scratch and claw every single moment just to keep your family alive”. Keep that in mind the next time somebody tells you there is a “light at the end of the tunnel”.

“25 Years Wiped Out in 25 Weeks” – The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation just issued a report which found that “in only half a year, the coronavirus pandemic has wiped out decades of global development in everything from health to the economy.” As reported in Politico, “After 20 years of continuous progress, almost 37 million people have this year become extremely poor, living on less than $1.90 a day, according to the report. ” Furthermore, “‘falling below the poverty line’ is a euphemism, though; what it means is having to scratch and claw every single moment just to keep your family alive”. Keep that in mind the next time somebody tells you there is a “light at the end of the tunnel”.

![]() It Isn’t Over, Till It’s Over – Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, warns that “the most dangerous phase of the COVID-19 crisis in the US may actually be now, not last spring. If the economy falters a second time, whether because of inadequate fiscal stimulus or flu season and a second COVID-19 wave, it will not receive the additional monetary and fiscal support that protected it in the spring.” We hope Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader McConnell are paying attention.

It Isn’t Over, Till It’s Over – Barry Eichengreen, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, warns that “the most dangerous phase of the COVID-19 crisis in the US may actually be now, not last spring. If the economy falters a second time, whether because of inadequate fiscal stimulus or flu season and a second COVID-19 wave, it will not receive the additional monetary and fiscal support that protected it in the spring.” We hope Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader McConnell are paying attention.