Abstract

For well over a decade, Puerto Rico has been stuck in a downward economic spiral that has only been worsened by natural disasters. Two hurricanes, a sequence of devastating earthquakes, a global pandemic, and the ever-present threat of more storms have erased what little steps may have been taken forward, and deepened the magnitude of the crisis to such an extent that a successful, just recovery seems unattainable. The Center for a New Economy (CNE) was among the first voices to alert of Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis. CNE’s Public Policy Director testified before Congress twice, once before the powerful Senate Committee on Finance and a month later before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources with jurisdiction over the U.S. territories.[1],[2] During that time, CNE argued that unless the island was granted tools to reduce poverty and increase labor workforce participation, Puerto Rico’s economic and fiscal crisis would simply remain unresolved. Four years since the enactment of the Puerto Rico Oversight Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), that argument is unfortunately proving true. Yet despite the bleak outlook, CNE has continued to shine a light on a path forward. In that vein, this policy brief is both retrospective and prospective. It will review key events and actions taken by the local and federal government that have led Puerto Rico to its current state. This includes a review of the legislative process that gave rise to PROMESA as well as the policies implemented by the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB) over the last four years. And it will conclude with a look at Puerto Rico’s present landscape and provide recommendations towards the future.

Introduction

Four years since the enactment of PROMESA, the island of Puerto Rico is still grappling with nearly 15 years of economic contraction and a bankruptcy process that appears to have no end in sight. Making matters worse, just a year after PROMESA was signed into law, Puerto Rico was struck by not one but two devastating hurricanes in a span of 14 days. The widespread destruction decimated Puerto Rico’s ability to meet debt obligations. That argument was confirmed by distinguished economists Pablo Gluzmann, Martin Guzman and Nobel laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz in January 2018: “If no expansionary aggregate demand policies are implemented to escape out of the current depression, the appropriate relief to restore sustainability will have to be the entire current stock of debt.[3] Paradoxically, the expectation of federal disaster dollars helped markets rally and significantly increased secondary market prices for the island’s junk-rated bonds. As it turned out, Puerto Rico’s misfortunes supposed additional profits for risk-prone investors. Perhaps if lawmakers had known in 2016 that the anticipated influx of additional federal dollars would be used to increase debt recoveries, they would have reconsidered the passage of PROMESA as we know it today.

As if these circumstances did not pose enough hardship, in early 2020 a series of earthquakes shook the island, causing significant damage to thousands of households and a temporary closure of all public schools.[4] Only months later, Puerto Rico also was enveloped by the global coronavirus pandemic and struck by extreme bouts of droughts and flooding that further exposed the threats of climate change. Today, as global temperatures continue to rise and the effects of climate change become more evident, so do the odds of getting hit by another powerful storm that could set us back even further.

This brief will summarize key events that took place prior to PROMESA’s passage, provide a high-level overview of the challenges still ahead, and provide recommendations to policymakers on what can be done to aid the beleaguered island.

The Making of PROMESA

To really understand Puerto Rico’s current state of affairs, we have to trace back the origins of its financial crisis. A prolonged economic recession has been strangling Puerto Rico since 2006 – a negative trend that many attribute to the expiration of industrial tax credits known as Section 936, but that also can be explained by misguided public policy, increased outmigration, high levels of government bureaucracy, rapidly-growing indebtedness, and austerity-based structural reforms, all of which were layered on top of an already fragile economy. Back in August 2013 a Barron’s article already highlighted the island’s weak fiscal position and high public debt. The author, Andrew Bary, presaged that unless Puerto Rico was able to turnaround its downward economic trend and make substantial cuts to government services, Puerto Rico would be walking the plank towards bankruptcy:

Puerto Rico might be able to extricate itself from its financial troubles, but that probably would require an extended period of growth in what has been a stubbornly moribund economy. While there doesn’t appear to be an imminent danger of default for bondholders, investors ought to question whether the government will continue to have the political will to impose painful measures on relatively poor Puerto Rican residents to service debt held mostly by affluent Americans. The tempting yields on Puerto Rico debt aren’t enough to compensate for the risk.[5]

That was in 2013. Less than a year later, Puerto Rico was engineering, perhaps unwittingly, its final debt issuance: $3.5 billion in junk-rated municipal bonds mostly to pay maturing debt and finance operational budgets.[6] As individuals and families who live paycheck to paycheck know, the odds of climbing out of a vicious debt cycle riddled with high interests and limited legal protections by taking on more debt are slim to none. Puerto Rico’s case was even more dire. There wasn’t even an option to file for bankruptcy, as an amendment to the U.S. Bankruptcy Code in 1984 excluded the island from such recourse.

Having no federal bankruptcy tools at its disposal, the Puerto Rican government lobbied the House Judiciary Committee to amend Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy code and include Puerto Rico under its provisions. The government’s efforts, however, were preempted by influential creditor groups and the Committee never seriously considered legislation to that effect. Thus, in June 2014, Puerto Rico’s legislative assembly enacted its own debt restructuring mechanism. The Puerto Rico Corporation Debt Enforcement and Recovery Act, commonly known as the Recovery Act or “la quiebra criolla,” would allow several public corporations such as the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, the Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority, and the Ports Authority to file for bankruptcy through legal structures set up within Puerto Rico law. But shortly thereafter, creditors with stakes in Puerto Rico’s public corporations lined up to challenge the law’s validity. Among other claims, creditors argued that the U.S. Federal Bankruptcy Code preempted Puerto Rico from such legal action, while the Commonwealth government, several lawmakers, and other defendants contended that the Recovery Act was meant to address the federal statutory gap:

“the Commonwealth has the power to enact a statute that allows a public corporation to modify the terms of its debt with the consent of a substantial number of affected creditors or through a court-supervised proceeding because the U.S. Supreme Court has acknowledged the power of states to enact their own laws for entities Congress has not rendered eligible under applicable federal law.[7]

The District and Appellate courts affirmed the plaintiff’s position, disregarding Puerto Rico’s inability to access Chapter 9. It must be noted that Puerto Rico’s position was not unreasonable because, whether due to congressional negligence or not, the island had been left in a legal limbo since 1984.[8] In the end, though, then Governor Alejandro García Padilla, facing a series of imminent defaults, accepted the inevitable and stated “the debt is not payable” in a televised address on June 29, 2015.[9]

An immediate negative reaction from the markets followed, forcing the federal government to engage, and quickly. In a matter of months, both the House and the Senate held hearings to address the financial turmoil. In response to congressional queries, the Obama Administration laid out in October of that year A Roadmap for Congressional Action to Address the Crisis in Puerto Rico.[10] The original legislative design called for: 1) a comprehensive debt restructuring authority, 2) independent fiscal oversight, 3) equitable treatment under Medicaid, and 4) individual tax incentives and economic development tools, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

By the end of 2015, the government of Puerto Rico was running out of cash, jeopardizing its ability to afford its financial commitments, support its residents, and provide essential services. Then House Speaker Paul Ryan committed to taking up the issue in the new year. This compromise was offered in exchange for Democratic support on a federal spending package for fiscal year 2016.[11]

At the beginning of the second year of the 114th Congress, numerous drafts of what would eventually become PROMESA were floated in the legislative branch. Democrats were fundamentally opposed to the imposition of a control board on Puerto Rico but argued that their hands were tied, as Republicans would not support a comprehensive restructuring mechanism without a board. Among these Republican voices was the Chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee with direct jurisdiction over the U.S. territories, Rob Bishop (R-UT). He and his colleagues argued in favor of strict financial controls similar to those of the Washington DC Control Board, a position that happened to be in lockstep with that of many creditors.[12] Puerto Rico had little to no say in the process, in large part because creditors exerted great influence over Congress and successfully delegitimized the voice of the island’s government. Creditors were also successful in pushing forth the dubious idea that centralizing Puerto Rico’s government, restricting certain financial controls, and cutting already dwindling budgets was a recipe for success.

Before the enactment of PROMESA, the judicial branch, through two separate rulings issued by the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS), concluded, yet again, that Puerto Rico is not a sovereign territory because it is ultimately subject to the plenary powers of the U.S. Congress.[13] Specifically as it relates to bankruptcy, on June 13, 2016, the SCOTUS held that Section 903 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code indeed pre-empted Puerto Rico from legislating the Puerto Rico Recovery Act.[14] The SCOTUS ruling helped justify the argument for congressional intervention via PROMESA. Many national organizations and the Obama Administration endorsed the federal law, asserting it was necessary to provide Puerto Rico with a stay on litigation and an orderly and comprehensive bankruptcy regime. A mere two weeks after the SCOTUS issued its ruling, PROMESA had made its way through both congressional chambers and onto the desk of President Barack Obama, who inked it on June 30, 2016.

The first drafts of PROMESA created a structure for a seven-member Oversight Board to represent the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and its instrumentalities. At the time, Puerto Rico had over 18 different types of debt issuers with a total bonded debt outstanding of $74 billion.[15] Moreover, Puerto Rico had also accumulated over $49 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. To refinance these debts, PROMESA gave Puerto Rico access to an unusual but comprehensive court-supervised debt restructuring process presided by a specially assigned district court judge.[16] Unlike Chapter 9 and the local Recovery Act, PROMESA created a bankruptcy regime that would cover the entirety of the Commonwealth’s debt. The regime is unique to Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories and not available to U.S. States. At the time and still today, many have argued that the federal law would set an unwanted precedent in the restructuring world – and while the jury is still out on whether that is true, it’s important to keep in mind that PROMESA came about as part of a contentious negotiation process where access to bankruptcy was contingent on the imposition of a powerful oversight board.

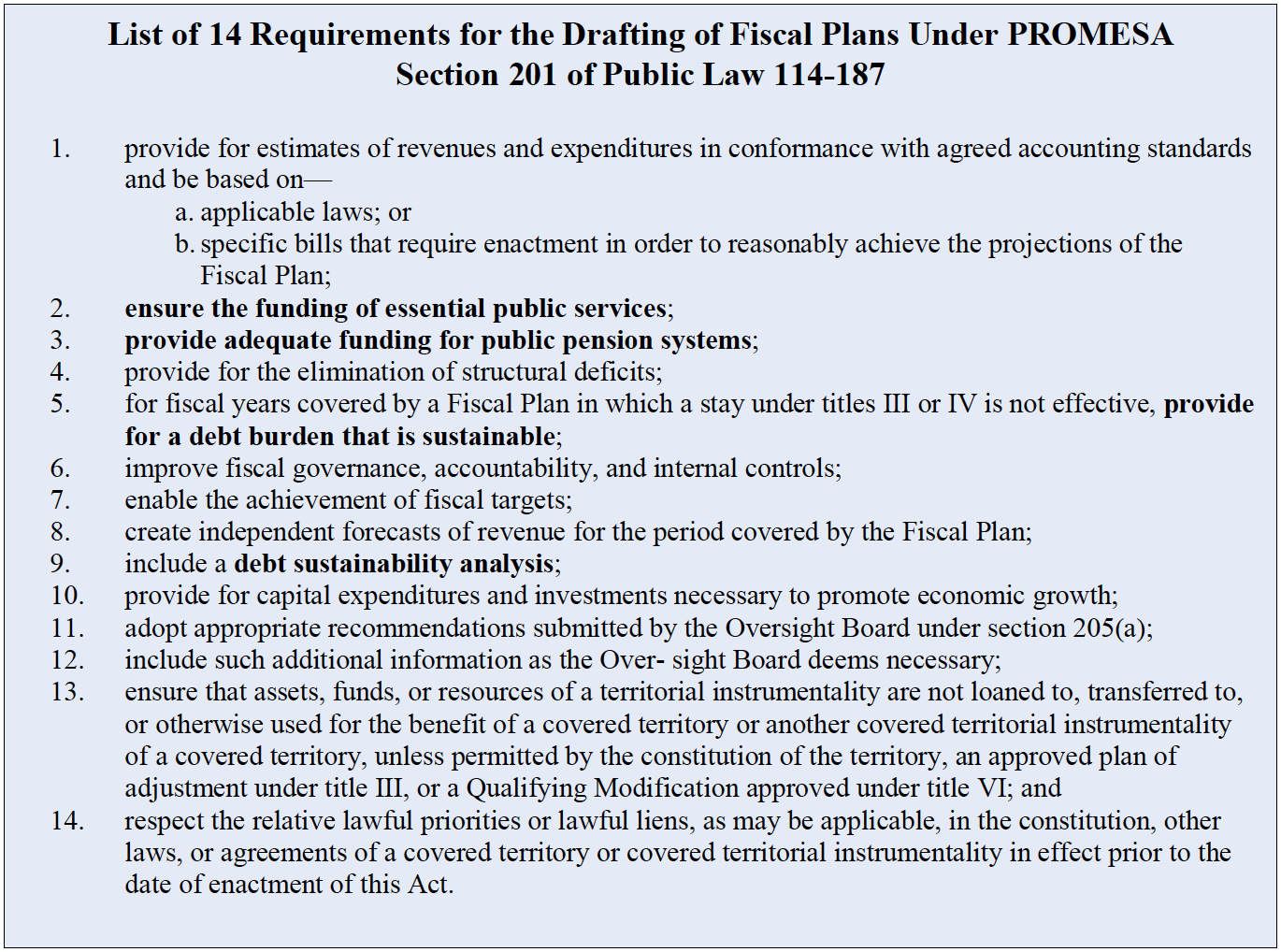

Among its core responsibilities, the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB) would possess sole discretion to approve and certify Fiscal Plans and act as debtor in any of Puerto Rico’s restructuring processes. Board members serve three-year terms with the possibility of reelection, and their stated goal is to achieve fiscal responsibility, which is defined in PROMESA as securing four consecutive years of balanced budgets and regaining access to the capital markets at reasonable rates. As such, only the Oversight Board – not the Puerto Rico government – acts as the debtor during restructuring negotiations, a power that many state officials would likely reject if their states were assigned such boards. As to Fiscal Plans, Section 201of PROMESA lists specific requirements on how to draft these five-year economic blueprints, many of which (as bolded below) have yet to be satisfied, according to numerous studies, on-the-record statements from government officials, court documents filed as part of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy, and other statements from island-based non-profits and community-based organizations.

PROMESA’s enactment came after a year of difficult negotiations between members of the House and Senate, many of whom knew very little about Puerto Rico generally, and much less about the island’s economic crisis. Opposition to PROMESA primarily came from a handful of anti-Wall Street groups and like-minded senators. But the law still drew overwhelming bipartisan support and passed the Senate with a 68-30 vote, following a rushed a procedural vote and one day’s worth of debate.[17]

As prescribed in PROMESA, President Obama soon appointed the seven members of the FOMB by selecting one member himself and another six from lists supplied by the majority and minority leaders of each congressional chamber. More specifically, PROMESA affords the U.S. Senate Majority Leader, then and now Mitch McConnell, to submit two lists from which the President must select two members. The same is true for the House Speaker, a seat that was then occupied by Paul Ryan. Meanwhile, the House and Senate minority leaders, then occupied by Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid, respectively, are afforded one list each. As such, Republican lawmakers had a hand in selecting most Board members (four of seven). Though there is no official documentation on who proposed each of the Board’s seven members, the selection reportedly happened as follows:

- President Barack Obama: Judge Arthur J. González

- House Speaker Paul Ryan: José B. Carrión III and Carlos M. García

- House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi: José R. González

- Senate Leader Mitch McConnell: Andrew G. Biggs and David A. Skeel

- Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid: Ana J. Matosantos

There is an alternative selection mechanism established in the law for the appointment of board members. Aside from the process described above, the other option allows the President to disregard the lists altogether and appoint his own list of candidates, subject to the Senate’s advice and consent.

Legal Challenges to PROMESA

At the time of appointing Board members, the federal government deemed that Senate confirmation was not required and pursued the first legal option. This procedural aspect would soon be challenged in litigation filed by hedge fund Aurelius LLC[18] in 2017 which argued that Board members are “officers of the United States” and therefore should be appointed by the U.S. President with the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate, as dictated by the Appointments Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Aurelius’ position was not endorsed by Judge Laura Taylor Swain, the chief magistrate presiding over the entirety of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy process. In the motion to dismiss the petition, she concludes

Affording substantial deference to Congress and for the foregoing reasons, the Court finds that the Oversight Board is an instrumentality of the territory of Puerto Rico, established pursuant to Congress’s plenary powers under Article IV of the Constitution, that its members are not “Officers of the United States” who must be appointed pursuant to the mechanism established for such officers by Article II of the Constitution, and that there is accordingly no constitutional defect in the method of appointment provided by Congress for members of the Oversight Board. Since the alleged defect in the appointment method is the only ground upon which Aurelius argues that the Commonwealth’s Title III Petition fails to comport with the requirements of PROMESA, Aurelius’ motion to dismiss the Petition is denied.[19]

After appeal by Aurelius, on February 15, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in Boston handed Aurelius a big victory after ruling that the appointment of board members was in violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Appointments Clause. According to the opinion, the powers granted to Congress under the Territorial Clause are limited not only when necessary to protect the fundamental rights of the residents of the territory but also by other “structural” limitations set forth in the U.S. Constitution, in this case, the Appointments Clause, which according to the Court “was designed to prevent congressional encroachment on the President’s appointment power, while curb[ing] Executive abuses by requiring Senate confirmation of all principal officers.”[20]

In response, the Oversight Board itself filed a writ of certiorari petition for the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case. The SCOTUS accepted the case and scheduled oral arguments in October 2019. Following months of deliberation, this summer the SCOTUS ultimately decided against Aurelius and sided with Judge Swain, holding that the U.S. Appointments Clause does not restrict the appointment of members to the Oversight Board.[21]

New Board, Same Challenges

Despite the favorable ruling, three Board members (Chairman José Carrión, Carlos García, and José Ramón González) recently announced that they would be stepping down. The vacancies, all of which happen to be Puerto Rican, would have to be filled in the same manner as they were appointed, according to PROMESA. As explained previously, the law also provides another appointment avenue that allows the President to disregard congressional nominees. This could prove to be a powerful tool for President Trump and the Republican-led Senate, especially if the tide turns against them in November and they effectively enter a lame duck period.

Regardless of what appointment process takes place, the almost simultaneous departure of three Board members is problematic, mostly because it takes time to learn the ins and outs of a novel law such as PROMESA, as well as getting acquainted with Puerto Rico’s longstanding economic issues. Moreover, the Board has implemented a revolving door of costly consultants, most of them from outside of Puerto Rico, instead of employing local, in-house personnel as a way to build long-lasting technical expertise in Puerto Rico. This is precisely one of the things the Board was envisioned to do. When PROMESA was being drafted in 2016, there was already broad concern about the detrimental effects of government agencies’ high turnover rates on their institutional knowledge. The Board was created under the notion that it would hire staff and develop its technical capacity internally. But the Board never followed suit. Instead, over the last four years, the Board has spent millions of dollars on outside consultants and advisors instead of investing those resources into nurturing local talent.

CNE was explicit on the negative consequences PROMESA would bear. First, giving up local governance in exchange for a chance at restructuring without an explicit assurance of debt relief was simply too much of a risk. It was as clear then as it is now that a body lacking local legitimacy would not be able to carry out its mandate. Second, while we acknowledged a need for establishing fiscal controls, CNE also argued that increased federal intervention in the island’s governance would not yield the intended results. Time has only proven us right.

After four years, public support for the fiscal body remains dismal and the island’s future is still uncertain. Puerto Rico continues to be embroiled in lengthy and costly legal battles and the island’s government is still reluctant to work with the Oversight Board, so much so that it has even filed lawsuits challenging many of the Board’s actions. To a certain extent, these challenges were to be expected, as similar financial boards established in New York and Washington, DC produced similar tensions. But unlike the fiscal support provided in other jurisdictions, Congress failed to provide any in Puerto Rico. While the very name of the law alludes to Economic Stability, PROMESA, its Board, and the federal government have failed to deliver the necessary tools to foster true economic growth in Puerto Rico. Considering the island’s acute poverty rates, PROMESA could have at least extended Puerto Rico better access into the country’s safety net, including programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. PROMESA, however, provides no such support. To the extent the federal government continues to enact laws that neglect Puerto Rico’s precarious situation, little change can be anticipated.

The Austerity Recipe

The COVID-19 pandemic has only magnified the importance of having governments that are well-equipped to handle unforeseen challenges. In Puerto Rico, dramatic cuts in government expenditures have curtailed basic services and diluted its capacity to respond effectively. Even before the pandemic, the island suffered through hurricanes and earthquakes that exposed the fragility of an ill-prepared and deteriorated government. Investments in all sorts of necessary infrastructure have been slashed or postponed due to lack of funding at the local level and uncertain funding at the federal level. These cracks have only grown wider during the pandemic.

According to Mark Blyth, a professor of International Political Economy at Brown University, “austerity is a form of voluntary deflation in which the economy adjusts through the reduction of wages, prices, and public spending to restore competitiveness, which is (supposedly) best achieved by the state’s budget, debts, and deficits.”[22] Since its inception, the Board has pursued an austerity agenda in Puerto Rico to no avail. Its austerity agenda also happens to be quite inconsistent. For example, while it orders downsizing in nearly all government agencies, it has awarded a bevy of contracts to outside consultants and lobbyists. The Board also argues that federal disaster aid will provide a great stimulus to Puerto Rico’s economy, yet the aid is only meant to compensate for what was damaged or destroyed, it’s much less than what was anticipated, and it continues to be severely delayed.

The Board has consistently ignored warning signs that its austerity-based measures are failing to deliver. Board member Ana Matosantos even raised this issue over two years ago when she voted against the Commonwealth’s April 2018 Fiscal Plan. Casting the only dissenting vote, Matosantos argued during the Board’s 12th meeting that “austerity measures that generate near-term surpluses but may very well lead to another fiscal cliff are not in the best interest of Puerto Rico, its retirees, creditors or its future.” She argued further: “I cannot support too much pain with too little promise.”[23] That same day, former U.S. Treasury economist Brad Setser also asserted: “I am suspicious that structural reforms will have a bigger impact than the austerity and fall-off in projected disaster spending…”[24]

The most recent Fiscal Plan was certified by the Board in May of this year to reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of this latest plan is that there is an acknowledgement, albeit subtle and narrow, that instituting stringent fiscal controls and imposing cuts on an already fragile economy during a highly uncertain environment may not be the most effective action plan. The revised plan therefore includes a one-year pause in its requirement for “right-sizing measures,” along with a pledge to pursue long-needed investments in critical healthcare infrastructure and recruit more health care providers.

The federal government also has begrudgingly recognized that it is investments, not cuts, in basic public services and infrastructure that allows government agencies to respond successfully in times of crisis. It took a global pandemic, historic levels of unemployment, and unprecedented spikes in poverty for the federal government to inject trillions of dollars into the economy via the CARES Act. And now that those funds are running out and need is still sky high, it has become too evident that much more will be needed in way of stimulus. As Mazzucato and Kattel have stated: “One of the biggest lessons is that state capacity to manage a crisis of this proportion is dependent on the cumulative investments that a state has made on its ability to govern, do and manage. While the crisis is serious for all, it is especially a challenge for countries that have ignored those needed investments…”[25] We agree with this assessment. After all, it is counterintuitive to expect an agency to reach more people and provide more services with less resources.

In early August, after another surge of coronavirus cases over the summer, the Oversight Board released its 2020 Annual Report to Congress. Notably, the report highlights the Oversight Board’s request to Judge Swain to halt her consideration of the Plan of Adjustment to allow for an assessment on the economic impact of the pandemic.

“Recognizing the importance of the ongoing Title III cases, but taking into account these realities [COVID-19 pandemic], FOMB presented motions requesting the Title III court to adjourn consideration of the proposed Plan of Adjustment for the Commonwealth and the proposed Restructuring Support Agreement for PREPA. The Title III court promptly granted these motions, and accordingly the hearings and deadlines related to the Commonwealth Plan of Adjustment and PREPA Restructuring Support Agreement are adjourned.”[26]

Recommendations

Through the enactment of PROMESA, important structural changes have come about in or around Puerto Rico’s government. Chief among them is the imposition of an unelected Board that acts as the island’s gatekeeper into bankruptcy. But Puerto Rico’s uneven and protracted political relationship with the U.S. has remained largely untouched and continues to negatively impact the island. As mentioned previously, Puerto Rico has been historically deprived of access into important federal programs comprising the country’s safety net.[27] Right where these programs are most needed is precisely where they are most absent. In this regard, Puerto Rico has never been afforded a level playing field, and it will certainly need one to overcome chronically high poverty levels and jumpstart its downtrodden economy. At best, the federal government has provided Puerto Rico with a long series of inconsistent and scanty patches that fully ignore the island’s long-term structural deficiencies. To avoid these temporary fixes, there must be the political will to permanently amend federal laws and regulation to strengthen the position of U.S. territories. There is little doubt that the most effective way of helping Puerto Rico is by discarding limited, piecemeal solutions and instead considering a broader agenda that remedies structural shortcomings so that Puerto Rico can focus its attention on economic growth.

As it stands, Puerto Rico still faces massive economic challenges that long predate the recent and wholly unfortunate series of natural disasters. While we can all agree that Puerto Rico’s levels of poverty, inequality, and outmigration are off the charts, the island’s government and Oversight Board have yet to put together a sensible, integrated, and well-articulated economic recovery plan. The absence of such a plan prevents Puerto Rico from making the necessary policy changes to bring about good governance and a thriving economy.

Of course, those structural inequalities were there long before PROMESA was enacted in 2016. The writing was also on the wall when it comes to the slow but steady deterioration of government institutions in Puerto Rico. In many ways, PROMESA is just one in a long list of federal government packages that have fallen woefully short of providing Puerto Rico with adequate relief. The same is true for the hurricane disaster aid that was assigned in 2017. Three years later, the evidence has clearly shown that many other places in the U.S. have enjoyed a faster recovery pace than others, particularly those with large low-income populations.

Puerto Rico also is in dire need of good leadership that can honestly and effectively implement higher accountability and transparency measures, as well as promote civic engagement. The island needs a radical transformation of its budgetary and fiscal practices to restore confidence in government. In February 2016, CNE proposed the adoption of a framework to do just this. As stated by my colleagues back then, the concept of fiscal rules:

“is predicated on the notion that a locally driven effort to overhaul key institutions, and the adoption of a well-designed fiscal rule, can transform Puerto Rico’s fiscal position and introduce much needed governance reforms that ensure the Commonwealth’s long-term fiscal solvency and sustainability.”[28]

But these local reforms can only work if the federal government truly commits to do its part, and this goes far beyond a board and a bankruptcy regime. The federal government must also account for Puerto Rico’s crushing debt and provide some flavor of quantitative easing, whether through a generous injection of federal funds, the purchase of debt, and/or a protection of its pension system. In the end, the federal government must come to terms with a simple reality: there cannot be proper accounting or accountability over broke and broken accounts.

For years now, the word “historical” has been used to categorize the challenges Puerto Rico faces. Similarly, the phrase “now, more than ever, Puerto Rico needs” has been used to advocate for solutions to its urgent needs. But how much longer can we continue uttering these platitudes without seriously addressing Puerto Rico’s longstanding faults? It is about time that the size of our actions matches the size of our words. Half-truths and campaign slogans simply won’t cut it anymore.

Endnotes

[1] Sergio M. Marxuach, Testimony Before the United States Senate Committee on Finance Public Hearing on Financial and Economic Challenges in Puerto Rico, September 29, 2015, Center for a New Economy.

[2] Sergio M. Marxuach, Testimony Before The United States Senate Committee On Energy and Natural Resources Public Hearing on Puerto Rico’s Economy, Debt, And Options for Congress, October 22, 2015, Center for a New Economy.

[3] Pablo Gluzmann, Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, An Analysis of Puerto Rico’s Debt Relief Needs to Restore Debt Sustainability, January 2018, Espacios Abiertos.

[4] Little over a month after the 5.9-magnitude earthquake, only 20 percent of public schools were considered structurally safe to reopen. See Danica Coto, Muy pocas escuelas abren tras sismo en Puerto Rico, January 28, 2020, Associated Press.

[5] Andrew Bary, Troubling Winds, August 26, 2013, Barron’s.

[6] Commonwealth of Puerto Rico’s $3.5 billion of General Obligation Bonds in 2014.

[7] On Petition for a Writ Of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, Melba Acosta-Febo, et al. v. Franklin California Tax-Free Trust, BlueMountain Capital Management, LLC, et al., August 26, 2015.

[8] Franklin California Tax-Free Trust v. Puerto Rico, Court of Appeals, 1st Circuit 2015.

[9] Michael Corkery and Mary Williams Walsh, Puerto Rico’s Governor Says Island’s Debts Are ‘Not Payable’, June 28, 2015, The New York Times.

[10] A Roadmap for Congressional Action to Address the Crisis in Puerto Rico, October 21, 2015, White House Task Force on Puerto Rico.

[11] Daniel Newhauser, Alex Brown and National Journal, The Ryan-Pelosi Relationship Passes its First Test, December 16, 2015, The Atlantic.

[12] Congressman Rob Bishop, Amicus Curiae: On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico, San Juan in No. 3:17-AP-00159-LTS, June 29, 2018.

[13] In the early 20th century the U.S. Supreme Court decided on a series of landmark cases, known as the Insular Cases, setting a historical precedent for the federal government’s authority over its territories.

[14] Slip Opinion, October Term 2015, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico Et Al v. Franklin California Tax-Free Trust Et Al, Supreme Court of the United States, June 13, 2016.

[15] For a comprehensive analysis of Puerto Rico’s debt structure see: Sergio Marxuach, The Endgame: An Analysis of Puerto Rico’s Debt Structure and Arguments in Favor of Enacting a Comprehensive Debt Restructuring Mechanism for Puerto Rico, April 2016, Center for a New Economy.

[16] Section 308 of PROMESA required the U.S. Chief Justice to designate a district court judge to preside over the debtor’s restructuring cases. Chief Justice John G. Roberts tapped on U.S. District Court Judge Laura Taylor Swain from the Southern District of New York.

[17] U.S. Senate Roll Call Vote Summary, 114th Congress, 2nd Session.

[18] Aurelius Capital Management is a U.S.-based hedge fund that has been the cause of costly litigation battles in other debt restructurings worldwide, most notably after its role in Argentina, when Aurelius was aptly dubbed a “vulture fund”.

[19] United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico, Opinion and Order Denying the Aurelius Motions to Dismiss the Title III petition and For Relief from the Automatic Stay, PROMESA Title III, July 13, 2018.

[20] Aurelius Investment, LLC, et al., v. Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico et al., United States District Court for the First Circuit, Appeals from the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico, February 15, 2019.

[21] Slip Opinion, October Term 2019, Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Aurelius Investment, LLC, et al., Supreme Court of the United States, June 1, 2020.

[22] Mark Blyth, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, 2013, New York: Oxford University Press.

[23] Transcribed from video. FOMB 12th Public meeting, April 19, 2018 (3:44).

[24] Brad W. Setser, The Oversight Board’s Latest Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico is Still Too Optimistic, April 19, 2018, Council on Foreign Relations.

[25] Mariana Mazzucato and Rainer Kattel, COVID-19 and public-sector capacity, August 29 2020, Oxford Review of Economic Policy.

[26] Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico. Fiscal Year 2020 FOMB Annual Report, July 31, 2020.

[27] In a forthcoming paper from the Michigan Law Review, University of Florida Levin College of Law professor Andrew Hammond thoroughly describes federal law disadvantages towards Americans in the U.S. territories from accessing public benefits in programs such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, and the Supplemental Security Income. Andrew Hammond, Americans Outside the Welfare State, July 13, 2020.

[28] Center for a New Economy, There is Another Way: A Fiscal Responsibility Law for Puerto Rico, February 2016.