Published on October 15, 2020 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

This week we welcome back an old friend, Jennifer Wolff, to the CNE family. After Hurricane Maria, Jennifer decided to dedicate her time to finishing her doctorate in 16th and 17th century Caribbean history. Having accomplished that task with her usual and customary excellence she now returns to CNE; this time to bring us her perspective on global issues as she analyzes them from her vantage point in Madrid. Please join me in welcoming her back. We know you will find her contributions to the Weekly Review to be both thoughtful and insightful.

We also continue our Focus 2020 series, with a look at industrial policy in Puerto Rico. While Puerto Rico faces many pressing issues in the short-term, such as the debt restructuring, the reconstruction of infrastructure damaged by Hurricane Maria, and the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to start thinking about mid- to long-term policies to sustain economic growth. We hope our look at industrial policy jumpstarts that process.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

A Message from the President and Founder

Dear friends and partners,

Today is a very special day for CNE as we welcome back to our faculty Jennifer Wolff, Ph.D. as Director of the CNE Policy Bureau based in Madrid, Spain.

A vital part of CNE’s mission has always been to maintain a global outlook and to aspire to world-class standards both for us as an organization and for Puerto Rico. This new expansion will broaden our scope of knowledge and resources and enhance our global reach.

A new richness and depth of insight, analysis, and expertise will be available to Puerto Rico now from CNE’s presence in San Juan, Washington, D.C., and Madrid. Moreover, this new addition strengthens CNE’s network and policy capacities at a time when we face a rapidly changing, interconnected, and globalized world.

By tapping both sides of the Atlantic as sources of knowledge, CNE is again raising the bar. Keeping abreast of global trends and having multiple vantage points will allow CNE to develop innovative insights for transforming our island’s economic, social, and institutional foundation and galvanize our work as Puerto Rico’s think-tank.

Miguel A. Soto-Class, CNE President and Founder

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Europe: Transformation During Pandemic Times

By Jennifer Wolff, Ph.D., Director, CNE Policy Bureau, Madrid

Spain will bet on the green economy and the digital transformation of its society after being particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. With more than 860,000 cases and 33,000 deaths recorded by mid-October, the Bank of Spain estimates that the Spanish economy will decrease between 10.5% and 12.6% during 2020. The country is facing one of the most severe economic contractions among advanced economies.

The Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan recently presented by President Pedro Sánchez (PSOE) seeks to turn-around this blow to the economy by setting the stage for an expansive spending policy that aims to shape state budgets for the next seven years. The Plan contemplates ten key policies, among which are the digitization and decarbonization of the economy, the renewal of its technological capital, the increased internationalization of Spanish companies, a greater integration of Spain into European transport corridors, the development of deeper energy interconnections with neighboring countries (France and Portugal), and the implementation of social policies that ensure the integration of women and precarious groups into the transformation process.

Part V – Industrial Policy

In an interview recently published by our friends at Sin Comillas, Professor Edwin Irizarry Mora stated that the current “stagnation, [is] a product of macroeconomic conditions that are still determined by the continuation of the economic depression. This translates into a weak capacity to produce endogenous wealth, with the obvious implications for employment, income, and the production of goods and services. If we add to this the institutional inability — as Dr. Francisco Catalá has insisted so many times — to transform the bases on which our economic system operates, we have the perfect formula to continue in this abyss, with no hope of improvement in the foreseeable future.”

He is right. Even if we set aside the economic harm caused by the 2017 hurricanes, the recent earthquakes, and the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear the Puerto Rican economy has been on a path of secular stagnation for at least a decade. This is not to say the reconstruction of the capital endowment damaged or destroyed by the natural disasters, or assisting both businesses and households adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are not important. Those are, however, necessary but insufficient conditions to reignite economic growth in Puerto Rico. As Professor Irizarry Mora correctly points out, we have to work on improving our anemic capacity to produce endogenous growth and on reforming our institutions.

In this installment of our Focus 2020 series, we take a look at how the implementation of a modern industrial policy could help on both fronts: generating endogenous growth and spearheading institutional reforms.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Industrial Policy in the 21st Century

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

In the early post-WWII years, industrial policy was defined as any government initiative that (i) stimulated specific economic activities, (ii) promoted structural change from low productivity to higher productivity activities, and (iii) fomented the change from traditional economic activities to more dynamic or “modern” activities.

The traditional case for industrial policy was based on the fact that the world is full of market failures and strong government intervention is necessary to overcome poverty traps. In general, there are two principal forms of market failure. The first type of market failure regards coordination failures, which occur when the return on one investment depends on whether some other investment is made. For example, building a hotel near a beautiful beach may be profitable if somebody builds an airport. Thus, coordination failures are traditionally solved through direct government investments or guarantees.

The other typical kind of market failure regards information spillovers. This occurs because the process of finding out the cost structure for the production of new goods or services is fraught with uncertainty. The first mover will find out whether something is profitable or not, if it is, he will be copied by other entrants, but if he fails, he bears the whole loss. Thus, private returns are lower than the social benefits and the market incentives for these activities are inefficiently low. Information failures usually require government subsidies to promote investment in new industries.

Those kinds of industrial policies have traditionally been subject to several critiques. First, some people argue that government failure is worse than market failure. Governments usually put in place expensive programs and unwieldy bureaucracies that are very difficult to modify or eliminate later on. In addition, these critics say, governments are not good at picking winners because market imperfections are rarely observed directly and industrial policies are usually implemented by bureaucrats that have little capacity to identify where the imperfections are or how large they may be. Finally, bureaucrats are supervised by politicians who are prone to corruption and rent-seeking by powerful groups and lobbies. Proponents of these critiques argue that governments should limit themselves to ensuring property rights, enforcing contracts, and providing macroeconomic stability. The market would take care of the rest.

Well, reality has not been kind to either set of expectations. On the one hand, import substitution, public planning, and state ownership did produce some economic successes, but where they got entrenched and ossified over time they eventually led to colossal failures and crises. On the other hand, economic liberalization, deregulation, and opening up to trade and investment benefited export activities, financial interests, and skilled workers but produced growth rates far short of what was expected; promoted rent-seeking by well-connected economic elites; and significantly increased income inequality around the world.

New Thinking on Industrial Policy

Over the last decade or so, several scholars have challenged the traditional paradigm of industrial policy as limited to activities mostly related to fixing market failures and coordination problems. Indeed, many countries are pursuing innovation-led “smart” growth, which requires certain types of long-run strategic investments. Mariana Mazzucato, among others, argue that “such investments require public policies that aim to create markets, rather than just ‘fixing’ market failures (or system failures).” The countries following this path, have “public agencies [that] not only ‘de-risked’ the private sector, but also led the way in terms of shaping and creating new technological opportunities and market landscapes” while finding “ways in which both risks and rewards can be shared so that ‘smart’ innovation-led growth can also result in ‘inclusive’ growth.” (Mazzucato, 2015)

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to meet one of those scholars who are rethinking the field of industrial policy. Robert Devlin is a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and the co-author of the book “Breeding Latin American Tigers: Operational Principles for Rehabilitating Industrial Policies” (UNECLAC /World Bank, 2011). In this book, Professor Devlin sets forth a comparative analysis of the industrial policies implemented in Australia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, and Sweden; identifies common principles among them; and proposes various ways to implement those principles in Latin America.

First, it is important to clarify that the meaning of the term “industrial policy” has expanded since the early post-war era. It now generally refers broadly to a group of institutions, programs, and public and private organizations working together to achieve an economic transformation in a given country or region.

Furthermore, the objectives of a modern industrial policy are not limited to promoting the transition from a traditional agricultural economy to a modern industrial economy based on manufacturing, but rather it seeks to identify economic sectors, for instance, high technology agriculture, advanced or specialized services, or sophisticated manufacturing, in which a country has an opportunity to create greater added value and thus generate economic growth, as well as new and better jobs.

In this sense, modern industrial policy can be described as a process of discovery and continuous learning that requires close collaboration and coordination between the public sector, the private sector, academia, labor unions and other non-governmental organizations, in order to generate a structural economic transformation in the medium and long term.

Three Strategic Components

According to Devlin, effective industrial policies have at least three elements in common. First, it is necessary to establish a national strategic vision for the medium and long term. Second, effective collaboration with the private sector, broadly defined, is a critical element. And third, consistency in the execution of industrial policy over time is essential for success.

The first component, the strategic vision, in turn requires a deep and intellectually honest analysis of the country’s economic situation, its advantages and disadvantages, areas of opportunity, and the capacity of its institutions and organizations to learn, collaborate, and evolve.

After carrying out this introspection exercise, the objective is to determine the strategic orientation of industrial policy in the medium and long term. Devlin has cataloged four strategic orientations, which are not mutually exclusive: (1) the attraction of foreign direct investment; (2) the internationalization of small and medium-sized national companies; (3) the promotion of exports; and (4) innovation. The capabilities identified in the first part of the analysis in turn determine the strategic orientation of the industrial policy. Thus, we see that some of the ten countries analyzed by Devlin, such as Ireland and Singapore, decided to work on all four strategic directions at the same time, while others such as Australia and Sweden were more selective and decided to focus their resources on only one or two strategic areas.

The second element — collaboration with the private sector — is extremely complex since it requires the capacity on the part of the state to coordinate initiatives and programs, first, between and among the different government agencies in charge of industrial policy and, second, between and among those agencies and the private sector.

In Ireland, for example, the office of the Taoiseach, or Prime Minister, coordinates this work, with the help of a permanent secretariat, the National Economic and Social Council, the National Economic and Social Forum, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment, the organization “Enterprise Ireland”, the Irish Development Agency, Forfás, a kind of government “think tank”, and the Advisory Council on Science, Technology and Innovation, among other agencies. Each of these agencies implements a part of the socioeconomic development plan that is updated every three years.

The state, in addition, must have the capacity to establish a productive collaborative relationship with employers, academics, union leaders, and other organizations. The participation of private sector organizations is very important because, while the state retains the power to implement public policy, it is the private sector that has the knowledge and information about the potential of new opportunities for economic development. However, the state, while establishing cooperation mechanisms with the private sector, also has to ensure the common good and avoid rent-seeking by unscrupulous businessmen or the capture of state institutions by private actors. Executing all these functions is an extremely complex task.

And precisely, the third element is the execution of industrial policy. According to Devlin, it is at this stage that many governments fail catastrophically. A country can design the best economic strategy in the world, but if its state institutions and the private sector cannot execute it, then the effort will not have any significant impact on the economy.

The importance of institutions at this stage cannot be underestimated. Indeed, some scholars argue that it is critical to get institutions “right” before thinking of specific economic policies. According to Dani Rodrik, a first-best policy in the wrong institutional setting will do considerably less good than a second-best policy in an appropriate institutional setting.

Again, it is necessary to think of industrial policy as an interactive process of strategic cooperation between the private sector and government; which on the one hand, serves to elicit information on business opportunities and constraints and, on the other hand, generates policy initiatives in response. The challenge is to find a middle ground for government bureaucrats between full autonomy and full embeddedness in the private sector. Too much autonomy for the bureaucrats and you minimize corruption but fail to provide what the private sector really needs. But if bureaucrats become too embedded with the private sector, then they may end up in the pocket of business interests.

And One More

In addition to the elements set forth by Devlin, implementing a successful industrial policy in the 21st century requires a fair apportionment of both risks and rewards between the state and the private sectors. According to Mazzucato:

Having a vision of which way to drive an economy requires direct and indirect investment in particular areas, not just creating the conditions for change. Crucial choices must be made, the fruits of which will create some winners, but also many losers…This situation suggests that it is necessary for such investments to be made in a portfolio approach with some of the upside gains covering the downside losses. In other words, if the public sector is expected to fill in for the lack of private venture capital (VC) money going to early-stage innovation, it should at least be able to benefit from the wins, as private VC does. Otherwise, the funding for such investments cannot be secured. (Mazzucato, 2015)

In an economic environment where government shapes markets, relying solely on tax revenues may not be sufficient to continually fund a dynamic industrial policy that entails making high-risk investments, many of which will probably fail. Therefore, as Dani Rodrik has suggested, using a portfolio approach to industrial policy means the state should be “able to reap a reward from the wins, in order to fund the losses and the next round. Such direct return-generating mechanisms must be explored, including retaining equity, a share of the IPR, and income-contingent loans.”

Reasons for Failure

Industrial policy can fail due to multiple causes. For example, in some countries the capacity of the state or the private sector to implement a given industrial policy is overestimated. This lack of capacity in turn produces an implementation gap between the plan’s objectives and the economic reality. That gap, eventually, translates into distrust, apathy, and skepticism between the various social actors and the government.

In other countries, the cause of the failure lies in the extreme politicization of the process and in the denial of spaces for participation in the development of the strategy to the political opposition or representatives of other important sectors. It is the participation deficit that eventually causes what Devlin calls the “refounding syndrome” that occurs when a political party comes to power and feels compelled to eliminate all the initiatives of the previous government as it perceives them as illegitimate. A phenomenon with which we are, unfortunately, quite familiar here in Puerto Rico.

Finally, failure can result from the lack of an independent system for evaluating and measuring results. In a process as complicated as this, it is inevitable that mistakes will be made or the potential of an economic sector is overestimated. The important thing is to identify the error in a timely manner, analyze what and why it happened, and promptly redirect resources to other sectors with greater potential.

Traditional Objections in Puerto Rico

When talking about industrial policy in Puerto Rico, two objections immediately arise, both of which are false. The first is that Puerto Rico does not have the political powers or the economic resources to carry out an industrial policy. In fact, Puerto Rico has spent decades negotiating investment agreements with multinational companies and in terms of resources, the consolidated budget already allocates billions of dollars, both in direct spending and tax incentives, for “economic development”. Where Puerto Rico has failed has been in establishing linkages between the foreign and domestic sectors, in enabling the formation of a national production network, and in efficiently coordinating government spending on economic development, which is generally carried out in a fragmented way.

The second objection is that the concept of industrial policy is foreign to the political economy of the United States. This statement could not be farther from the truth. From its inception to the present day, both the federal government and many states have implemented various kinds of industrial policies, either in a formal and structured way or in an informal and tacit way. For example, on December 5, 1791, Alexander Hamilton presented to Congress his “Report on the Subject of Manufactures” recommending an economic policy to stimulate the economic growth and industrialization of the newly created nation.

In more recent times, US industrial policy has been carried out through various agencies, such as NASA, the Department of Defense, and the National Institutes of Health. In fact, many scientific advances, from the creation of the Internet and GPS to basic research in biology and chemistry for the production of medicines, have been funded or subsidized by the federal government. On the other hand, at the state level, almost all states, both large ones like Florida and Texas, and small ones like South Carolina, have developed industrial policies to grow and develop the state economy, and in some cases, the regional one.

Conclusion

In summary, if Puerto Rico truly wishes to straighten the course of its economy, it is imperative to design a modern industrial policy that puts us at the forefront of global economic activity and to create the public and private institutions necessary to implement it.

Data Snapshot

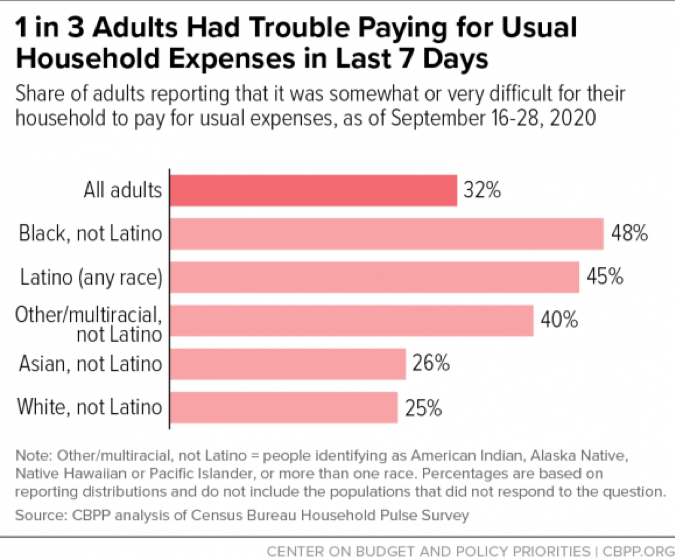

A recently published analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that “nearly 78 million adults — about 1 in 3 — are having trouble paying for usual household expenses”, according to Census data. “Along with other data showing that hardship has significantly worsened due to COVID-19 and its economic fallout, the figures underscore the urgent need for policymakers to resume negotiations — which the President ended abruptly yesterday — and enact a robust, bipartisan economic relief package.”

On Our Radar...

![]() Moderna Won’t Enforce Vaccine Patents – Forbes magazine has reported that “U.S. vaccine frontrunner Moderna says it will not enforce its Covid-19-related patents while the pandemic continues, a decision that would allow other vaccine-makers to make use of the company’s technology.” Which is only fair, since the company has received hundreds of millions of dollars from the federal government to support the development of its vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Moderna Won’t Enforce Vaccine Patents – Forbes magazine has reported that “U.S. vaccine frontrunner Moderna says it will not enforce its Covid-19-related patents while the pandemic continues, a decision that would allow other vaccine-makers to make use of the company’s technology.” Which is only fair, since the company has received hundreds of millions of dollars from the federal government to support the development of its vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

![]() The Pandemic Worsens Income Inequality – According to the Wall Street Journal, “The comeback since the start of the pandemic is kind to those who can work from home, to firms serving them and to regions hospitable to them. Left behind are the less-educated, old-line businesses and areas dependent on tourism. Rising wealth coincides with lines at food banks.”

The Pandemic Worsens Income Inequality – According to the Wall Street Journal, “The comeback since the start of the pandemic is kind to those who can work from home, to firms serving them and to regions hospitable to them. Left behind are the less-educated, old-line businesses and areas dependent on tourism. Rising wealth coincides with lines at food banks.”

![]() The Puzzle of US Trade with China – Brad Setser from the Council on Foreign Relations asks whether China’s surplus with the United States is back at a record level. His answer is: “It depends. In China’s data, China’s exports to the United States and its surplus with the United States are at all-time highs. The United States’ import data, however, shows fewer imports from China than China reports exports—which is interesting, because the norm has long been the other way around.”

The Puzzle of US Trade with China – Brad Setser from the Council on Foreign Relations asks whether China’s surplus with the United States is back at a record level. His answer is: “It depends. In China’s data, China’s exports to the United States and its surplus with the United States are at all-time highs. The United States’ import data, however, shows fewer imports from China than China reports exports—which is interesting, because the norm has long been the other way around.”