Published on October 22, 2020 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

Friends, it is late October and we are well into autumn. We were taught back in grade school that “there is no change of seasons” in Puerto Rico. But that is wrong. If you observe closely you can notice subtle but significant changes in plants and trees; the temperature, the length of days, and above all the sunlight.

Autumn light is “Soft, forgiving, it makes all the world an illuminated dream. Dust motes catch fire, and bright specks drift down from the trees and lift up from the stirred soil, floating over lawns and woodland”…it “always makes me think of fiery motes of chalk dust drifting in the expectant hush of an elementary school classroom during story time, just before the bell rings and sets the children free”, writes Margaret Renkl for the New York Times.

Indeed, there is something sublimely transcendent about that autumnal light, hanging low on the horizon, painting the landscape the color of old whiskey, crisper, brighter, and warmer than the winter’s hollow sun, and which, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, cuts “through the smoke rings of our mind”, to guide us “down the foggy ruins of time”.

Perhaps those sepia tones activate long-dormant neuronal circuits deep in the recesses of our brains; bringing back memories of childhood vacations with family and friends; of the girl that got away; of those who have moved on to the other side and that, more than anything else, we long to embrace.

It’s a complex set of emotions this autumn brings. It is neither nostalgia nor melancholia either, but something rather more complicated. It is perhaps something akin to the feeling of Istanbul’s hüzün, which as described by Orhan Pamuk “is not just the mood evoked by its music and its poetry, [but] a way of looking at life that implicates us all, not only a spiritual state but a state of mind that is ultimately as life-affirming as it is negating.”

Yes. Something like that.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Part VI – Universal Basic Income

The COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on both the economic insecurity that has been affecting workers for decades now — stagnating incomes, dead-end jobs without benefits that pay the minimum wage for years, lack of access to health care, rising inequality — and the deficiencies of the U.S. social safety net. It took many weeks, months in some cases, to get assistance to millions of people who lost their jobs this spring due to the economic impact of the pandemic. And now that assistance is running out, with unemployment still high, a new surge of infections on the horizon, and Congress unable to agree on a new aid package.

There has to be a better way of doing this, many people say. It turns out there actually is a better way. It’s called a Universal Basic Income (“UBI”), an old idea whose time may have finally come.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Universal Basic Income – The Basics

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

The idea of providing a basic income—a universal, regular, unconditional cash payment distributed by the government—is not new. Thomas More mentioned a form of this program in Utopia (1516), while Thomas Paine (Agrarian Justice, 1796) favored a similar program shortly after the U.S. war of independence. More recently, the idea has been favored by those on the right, such as Friederich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Richard Nixon, in the form of a “negative income tax”, as well as by those on the left, such as John Kenneth Galbraith, James Tobin, and George McGovern, among others.

Universal Basic Income – The Ideal

We base our analysis on the “model” or “ideal” UBI described by Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght in their book, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy (Harvard, 2017). Their definition of the UBI is actually rather simple: a universal basic income means “a regular cash income paid to all, on an individual basis, without a means test or work requirement.” Let’s take a closer look at each of these elements.

A basic income, by definition, implies the amount is not enough to survive on by itself. The idea is rather to provide a floor that provides stability when unexpected life events occur, such as unemployment, illness, or a natural disaster, among other similar incidents. This means there is flexibility in designing the program depending on how high a floor a given society deems appropriate.

An individual income means the benefit is provided independently of the household situation. That is, it is irrelevant whether the recipient is married, divorced, widowed, or co-habiting with someone or whether there are children in the household. This has at least three benefits. First, it respects individual autonomy given that receipt of the UBI is not conditional on conforming to any given lifestyle or family structure. Second, it provides a modicum of financial support for people who want to break free from abusive relationships. And, three, it cuts backs on administrative costs, as there is no need to have an army of nosy caseworkers visiting recipients to verify their family status, while liberating beneficiaries from interacting with intrusive bureaucrats.

A cash income maximizes flexibility in using resources, reduces bureaucracy and administrative costs, and “leaves the beneficiary free to decide how to use it, thus allowing individual preferences to prevail among the various options available.” The benefits of cash payments became palpably clear this spring when the federal government provided one-time payments of $1,200 to every person with an income of $75,000 or less. In contrast with in-kind assistance, providing cash meant that people could use it the money to meet whatever need they understood to be most pressing: for example, paying the mortgage, buying medicines, or getting a laptop to allow a child to take school classes from home.

Advocates of providing in-kind assistance argue that providing cash increases the likelihood the money would be wasted. Yet study after study demonstrates that is not the case. Pilot programs since the 1970s in Manitoba, Canada have shown that beneficiaries spend well north of 95% of funds on necessities such as food, healthcare, or shelter. Indeed, that has been the recent experience in the City of Stockton, California, which is running a UBI pilot program.

A universal income means that receipt of the UBI is not subject to an income or means test. This feature of the UBI is controversial because it increases its cost significantly and it means that extremely wealthy people would benefit. Yet, there are good reasons for structuring the program in this way. The first one is philosophical in that universality seeks to eliminate an invidious distinction that has been made since Biblical times between the “deserving” and the “undeserving” poor. The former, usually defined as widows, orphans, and the extremely sick or disabled, were deemed “deserving” of public help as they were poor due to no fault of their own. The latter, however, were deemed to be just lazy vagabonds who did not “deserve” any help unless they were “willing” to work (never mind that sometimes there were no jobs to be had). Hence the creation of that terrible institution known as the “workhouse.” Second, universality removes at least some of the social stigma associated with receiving government assistance as there is no shame in receiving a benefit that is also paid to everybody else.

Perhaps most important, universality addresses what Van Parijs and Vanderborght call the “unemployment trap”. Under traditional means-tested assistance programs, beneficiaries lose part or all of their benefits if they decide to work in even the most precarious job. Facing a marginal tax rate of 100% or more, means many welfare beneficiaries decide either not to work or to work in the informal economy, often under dangerous conditions. In this context, universality means any earnings people do generate go to increase their net income, thus removing a strong disincentive to work associated with traditional means-tested programs.

Finally, an obligation-free income, means there is no obligation for its beneficiaries to work or be available to work on the labor market. This is perhaps the most controversial characteristic of the UBI. Yet, freedom from obligation addresses another “trap” associated with traditional public assistance programs, namely the “employment trap”. Currently, many public assistance programs require beneficiaries to work or engage in “work-like activities”, which means they often end up accepting “lousy or degrading” jobs (Van Parijs and Vanderborght’s words, not mine), offered by unscrupulous employers who know welfare recipients could lose their benefits if they lost their jobs. A UBI program that provides an obligation-free income addresses this potential for exploitation by making it easier to say “no” to unattractive, low-paying jobs.

Some Objections

As the reader can imagine, many objections to the UBI have been put forward by critics from both the left and the right. Here we can only address a few of them, but those interested in a full analysis of the ethical, economic, and political objections to the UBI are well-advised to read Van Parijs and Vanderborght’s book. For those less inclined to do a deep dive into the policy weeds, we recommend reading Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World (Crown, 2018) by journalist Annie Lowrey.

First, poll data shows that many people seem to believe that it is “unfair for able-bodied people to live off the labor of others.” If we assume this argument is made in good faith and is not based on classist stereotypes, then it must be based on some notion of social reciprocity that would be “violated” by people who receive a basic income without working. It would amount to some form of “free-riding”.

At first glance, this argument appears convincing but falls on its own upon closer scrutiny. As Van Parijs and Vanderborght argue, “if one is serious about denying an income to those able but unwilling to work, this denial should apply to rich as well as to the poor.” That is, there is a double standard at work here, one for hedge-fund managers sailing the Mediterranean and another for people who work forty hours a day for the minimum wage. In the acerbic words of John Kenneth Galbraith: “Leisure is very good for the rich, quite good for Harvard professors—and very bad for the poor. The wealthier you are, the more you are thought to be entitled to leisure. For anyone on welfare, leisure is a bad thing.” Second, if we are really concerned about free riding the main worry, according to Van Parijs and Vanderborght, “should not be that some people get away with doing no work, but rather that countless people do a lot of essential work end up with no income of their own”, for example, people who may be in school, taking care of sick relatives, or simply managing their home.

The second objection we want to address goes back to Karl Marx, who opposed schemes similar to the UBI in the 19th century by arguing that it would depress the level of wages because “the bottom constraint, subsistence, has fallen away”. This is not necessarily true, but to understand why we must go back to the universality and obligation-free characteristics of the UBI. The universality condition would make it easier to accept attractive but low-paying jobs such as apprenticeships and internships and thus would tend to lower the overall level of compensation.

On the other hand, freedom from obligation condition allows people to reject low-paying, unattractive jobs. When the demand for “lousy” jobs declines, employers can try to automate them. If that is not possible, they may try to make them more attractive, but where this is impossible or too expensive, they will have to increase the wages they pay. Therefore, “those lousy, poorly-paid jobs which you would not dream of doing will need to be paid better.” The net effect on wage levels, thus, is uncertain. However, the effect on the “worst-paid existing jobs can safely be expected to be positive.” Second, nothing in the UBI is inconsistent with minimum wage laws and regulations.

Finally, the third objection worth mentioning here is cost. A UBI is expensive, quite expensive. However, it is not so expensive as to be unaffordable. First, the total cost would depend on the level of basic income provided. Second, as the program is implemented it will be necessary to increase tax revenue and replace many of the current means-tested programs. This will generate fiscal space for the program. Third, we need to take into account not only the costs, but also all the benefits associated with it, both in monetary and non-monetary terms.

Conclusion

Until recently the UBI was an idea popular only among academics and “the kinds of people who wore T-shirts sporting jokes disguised as mathematical equations. It was something of a fringe interest.” Yet the pandemic changed all that. Indeed, the CARES Act included a partial, temporary basic income in the form of $1,200 payments to people below a certain income threshold and an extra $600 added to basic unemployment benefits.

As we struggle with the economic damage wreaked by the pandemic political support for the UBI may increase. On the “liberal” side, it would mean providing a floor for all people to withstand the economic downturn, while getting rid of “safety net programs that fail to catch many people and in which many others get trapped.” On the “conservative” side a UBI means a hard-budget constraint, few rules, and no new bureaucracies. But perhaps more important, it would allow us to “attack the root cause of troubles for both those who get sick by working too much and those who get sick because they cannot find jobs.” A worthy goal, indeed.

From Our Bureau in Madrid

This week the Director of our Bureau in Madrid, Jennifer Wolff, analyzes how austerity policies have eroded the Spanish government’s capacity to address the COVID-19 pandemic in that country. This is a topic close to all of us in Puerto Rico, as our government has struggled to roll out a comprehensive program to test people, trace contacts, manage data, coordinate with healthcare providers, and treat patients in a timely manner. This lack of state capacity is due, in large part, to the impact of years of poor governance and austerity policies that have weakened the island’s government’s ability to perform even the most essential of services.

Spain: The Deadly Cost of Austerity and Poor Governance

By Jennifer Wolff, Ph.D., Director, CNE Policy Bureau, Madrid

As COVID-19 cases surge again in Europe and key cities like Paris, Berlin and Barcelona take extraordinary measures to curtail the expansion of the virus, Spain’s management of the pandemic has come again under scrutiny. The prestigious international medical journal The Lancet has published yet another stark evaluation of the country’s response to the pandemic, stating – in a sobering warning to all countries struggling to contain the disease – that “Spain’s COVID-19 crisis has magnified weaknesses in some parts of the health system and revealed complexities in the politics that shape the country”.

The article COVID 19 in Spain: A Predictable Storm? identifies several factors that have laid bare the frailties of the Spanish health system and the reasons for its seeming incapacity to deploy a robust response: weak epidemiological surveillance structures, low capacity for PCR testing, scarcity of both personal and critical care equipment, a lack of preparedness in nursing homes, and conspicuous inequalities in care among social groups. All these weaknesses, the journal notes, are the result of a decade of austerity that has notably reduced the system’s ability to adequately manage the pandemic.

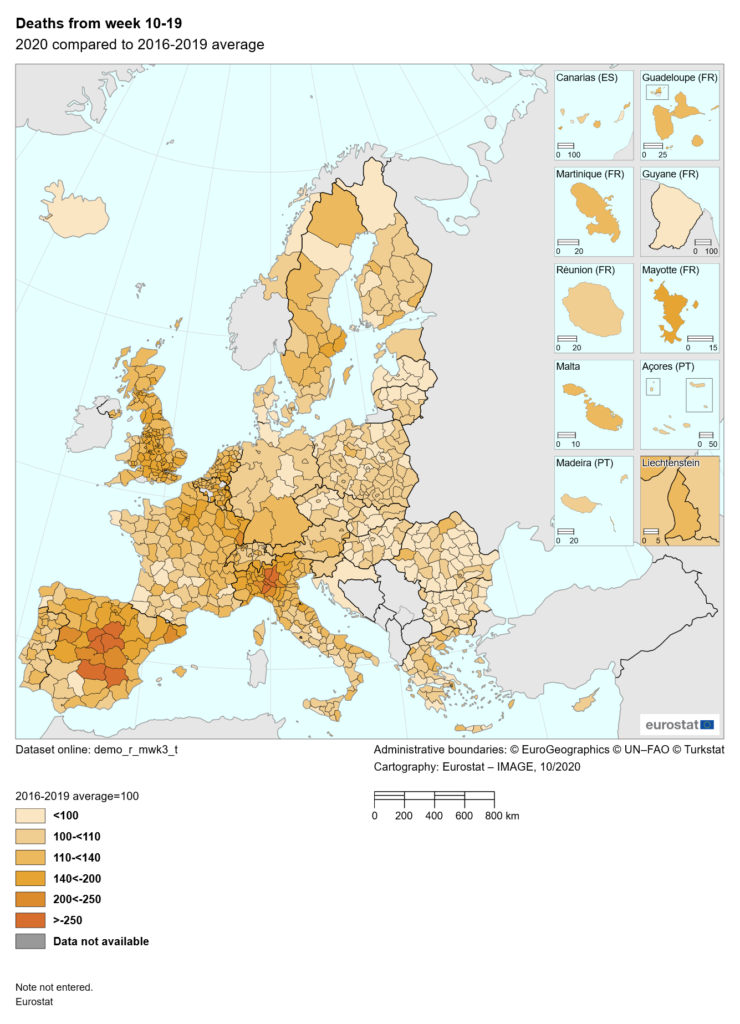

Between March and June 2020, Spain registered the largest increase in deaths (excess deaths) of all Europe. Some regions of the country have been among the hardest hit by the pandemic. Excess deaths are tabulated comparing all deaths registered during the pandemic with those registered during the same period in past years.

Map: Eurostat, “Deaths in weeks 10 to 19, 2020 compared to 2016-2019 average”

Data Snapshot

Public Investment for the Recovery

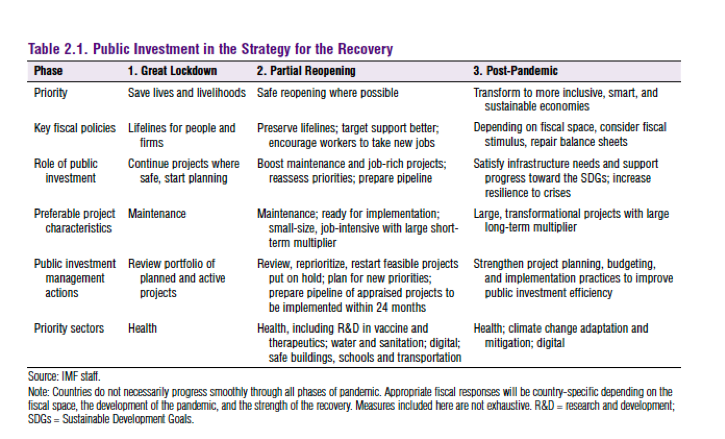

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, October 2020

According to the International Monetary Fund, “the immediate focus of governments during the COVID-19 crisis thus far has appropriately been to address the health emergency and provide lifelines for vulnerable households and businesses. Governments now also need to prepare economies for safe and successful reopening, foster recovery in employment and economic activity, and facilitate transformation to a post-pandemic economy that, with the right policies, can be more resilient, more inclusive, and greener. Public investment can make a crucial contribution toward these goals.” See the table above for a summary of the public investment strategies recommended by the IMF.

On Our Radar...

![]() “A Long and Difficult Ascent” – That is how the IMF describes the path ahead, in words that inevitably will remind many of the Beatles’ Long and Winding Road. Specifically, the Fund’s Research Division says “the global economy is climbing out from the depths to which it had plummeted during the Great Lockdown in April. But with the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to spread, many countries have slowed reopening and some are reinstating partial lockdowns to protect susceptible populations. While recovery in China has been faster than expected, the global economy’s long ascent back to pre-pandemic levels of activity remains prone to setbacks.”

“A Long and Difficult Ascent” – That is how the IMF describes the path ahead, in words that inevitably will remind many of the Beatles’ Long and Winding Road. Specifically, the Fund’s Research Division says “the global economy is climbing out from the depths to which it had plummeted during the Great Lockdown in April. But with the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to spread, many countries have slowed reopening and some are reinstating partial lockdowns to protect susceptible populations. While recovery in China has been faster than expected, the global economy’s long ascent back to pre-pandemic levels of activity remains prone to setbacks.”

![]() Lockdowns Lead to Faster Economic Recoveries – The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook “shows that government lockdowns — while succeeding in their intended goal of lowering infections—contributed considerably to the recession and had disproportional effects on vulnerable groups, such as women and young people. But the recession was also largely driven by people voluntarily refraining from social interactions as they feared contracting the virus. Therefore, lifting lockdowns is unlikely to lead to a decisive and sustained economic boost if infections are still elevated, as voluntary social distancing will likely persist.”

Lockdowns Lead to Faster Economic Recoveries – The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook “shows that government lockdowns — while succeeding in their intended goal of lowering infections—contributed considerably to the recession and had disproportional effects on vulnerable groups, such as women and young people. But the recession was also largely driven by people voluntarily refraining from social interactions as they feared contracting the virus. Therefore, lifting lockdowns is unlikely to lead to a decisive and sustained economic boost if infections are still elevated, as voluntary social distancing will likely persist.”

![]() The Week Austerity Died? – The Financial Times reports that “This was the week we witnessed the funeral of austerity. Those who used to worship at its altar now urge countries to throw caution to the wind. Fiscal orthodoxy, practised over decades since the debt crises and inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, has been replaced with fiscal activism. As the IMF and World Bank annual meetings wrap up in virtual form in Washington this weekend, many of the most senior figures at the top — and in the research departments — of these institutions have been singing a new tune on fiscal policy this week.” We can only wish this were true. However, we fear the news of austerity’s demise may be premature. It was Keynes, after all, who said it was surprising how many highly educated people, of otherwise impeccable judgement, remained bewitched by the “words of some long-defunct economist.”

The Week Austerity Died? – The Financial Times reports that “This was the week we witnessed the funeral of austerity. Those who used to worship at its altar now urge countries to throw caution to the wind. Fiscal orthodoxy, practised over decades since the debt crises and inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, has been replaced with fiscal activism. As the IMF and World Bank annual meetings wrap up in virtual form in Washington this weekend, many of the most senior figures at the top — and in the research departments — of these institutions have been singing a new tune on fiscal policy this week.” We can only wish this were true. However, we fear the news of austerity’s demise may be premature. It was Keynes, after all, who said it was surprising how many highly educated people, of otherwise impeccable judgement, remained bewitched by the “words of some long-defunct economist.”