Published on October 29, 2020 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

This week we reintroduce the idea of a fiscal rule for Puerto Rico, as part of our Focus 2020 Series. A fiscal rule is a legally binding process, ideally embedded in the constitution, to regulate a jurisdiction’s tax, spending, and debt policies. Puerto Rico will have to enact a rule of this kind eventually, whenever the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board is done with its work, if we want to avoid another fiscal crisis in the future.

In addition, Rosanna Torres, Director of CNE’s Office in Washington, D.C., writes about the potential adverse effects of a proposal to eliminate the requirement to file an Electronic Export Information report for shipments to and from the United States and Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Finally, we would be remiss if we didn’t mention that we are only five days away from the general election. Most polls and forecast models have Vice President Joseph Biden defeating President Donald Trump. Then again, they also had Trump losing in 2016, and look where we are… Read our last piece of this edition on the intricacies of the election process in the U.S. for a look at the Electoral College process and its implications for this year’s elections.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Part VII – Fiscal Responsibility and Fiscal Rules

In 2016 the federal government decided to establish a fiscal oversight board for Puerto Rico, similar to the one adopted in Washington, D.C., to essentially command all aspects pertaining to government budgeting and spending. We strongly believed back then that imposing an unelected board was not the only option available and that there was another way forward.

Therefore, we presented a series of specific policy proposals that would have laid the groundwork for a broad overhaul of Puerto Rico’s fiscal infrastructure. Our approach was predicated on the notion that a locally-driven effort to overhaul key institutions, and the adoption of a well-designed fiscal rule, could transform Puerto Rico’s fiscal position and introduce much-needed governance reforms to ensure the Commonwealth’s long-term fiscal solvency and sustainability, while addressing legitimate federal concerns and recognizing valid political qualms on the island.

Unfortunately, our proposals fell on deaf ears, as members of Congress, the U.S. Executive, rapacious bankers, and a group of Puerto Rican collaborators successfully advocated for the implementation of the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”) for Puerto Rico.

Four years later, the FOMB has failed to make substantial progress in accomplishing the statutory goals it was mandated to achieve: the few debt restructurings that have been executed have been overly generous with bondholders; little progress has been made to balance the central government budget, and; nothing has happened under the much-touted Title V that would ostensibly “expedite” critical infrastructure projects.

On the positive side, Puerto Rico has been able to (1) benefit from the stay on lawsuits seeking payment on the defaulted debt and (2) finance the cost of providing essential government services using funds that otherwise would have been paid to debtors.

Nonetheless, the enactment of PROMESA has not prevented the filing of dozens of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality and/or legality of actions undertaken by both the government of Puerto Rico and the FOMB. In addition, just as we warned back in 2016, the complex, iterative process instituted by PROMESA to craft both the annual budget and the Five-Year Fiscal Plan has proven to be unworkable in practice and has rendered Puerto Rico essentially ungovernable.

It is in this context that we take another look at our proposal for a fiscal rule for Puerto Rico.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Fiscal Rule for Puerto Rico

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Ph.D., Research Director

Principal Characteristics of Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Responsibility Laws

Fiscal rules may be broadly defined as mechanisms that allow for the establishment of monitorable fiscal targets and strategies. They have become popular since the 1990s and are currently a common feature in countries throughout Europe, Asia, and Latin America. The desire to establish a permanent institutional mechanism has led in turn to the adoption of Fiscal Responsibility Laws (FRLs). These FRLs vary substantially, as they must be tailored to specific political, institutional, and economic contexts.

Most FRLs include two key features: procedural and numerical rules. Procedural rules usually provide principles for sound fiscal management, reporting requirements, and accountability measures, while numerical rules offer precise fiscal targets that need to be met, most commonly regarding deficits, debt levels, and savings.

Procedural rules help improve institutional weaknesses, increase transparency, and help curb agency problems by increasing voter accountability of public officers. In addition, process improvements may also accelerate the transformation of the overall fiscal environment. Better reporting guidelines and more accurate information, for example, can go a long way to improve the decision-making process of key public agents.

Numerical rules are often associated with reductions in expenditure bias and providing clear targets that limit the discretion of creative budget makers with political biases. But assigning and adhering to hard numerical targets also raises some problems especially during periods of economic downturns when fiscal flexibility is warranted.

The underlying institutional framework that supports the FRL is of utmost importance. Weak or badly designed public financial management (PFM) systems will certainly threaten the efficacy of an FRL. The existence of transparent and accountable practices for preparing budgets, independent monitoring agencies, medium-term fiscal frameworks, reliable accounting, and statistical standards, amongst other institutional requirements, are essential to the efficient implementation of the provisions contained within a FRL. Thus, in terms of sequencing, countries that aim to adopt and implement an FRL should begin by reforming and improving its PFM systems, and gradually introducing procedural and numerical targets.

Finally, strict enforcement mechanisms are crucial to the effectiveness of FRLs. While it is expected that legislators and other public officials monitor compliance, the press and non-governmental watchdog organizations can also play an important role in making sure that benchmarks are met and that sanctions are swiftly applied. In countries with a weak enforcement track record, independent monitoring and oversight may be required. In addition, FRLs require broad political buy-in. If the public agents and political actors who will be at the center of ensuring implementation and monitoring are not in agreement with the law, or do not agree on the need for deep fiscal reforms, then enforcement will be weak and sanctions ineffectual.

Recommendations for a Puerto Rico Fiscal Responsibility Law

We propose that the Commonwealth’s legislative assembly enact a comprehensive Fiscal Responsibility Law with two components: (1) a simple, intuitive, and objective fiscal rule; and (2) procedural guidelines that support a large-scale overhaul of Puerto Rico’s public financial management systems, institutions, and practices.

For the purposes of this analysis, “institutional overhaul” refers not only to particular administrative and management fixes that need to occur within public agencies, but also to broader changes in the legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks that affect social and economic behaviors within Puerto Rican society. As numerous economists have argued, quality institutions (in the broader sense of the term) are central to the task of achieving economic development and growth, in large part because they help shape the different arrangements that support production and exchange.

(1) A Fiscal Rule for Puerto Rico

A well-designed, robust fiscal rule takes into account the cyclicality of government revenues while providing for debt sustainability over the long-term. Therefore, we propose a rule for Puerto Rico requiring that annual General Fund spending shall not exceed (1) cyclically adjusted revenues, as determined and certified by an independent panel of professional economists and other fiscal policy experts, minus (2) a small structural surplus. Within that limitation, the Puerto Rican legislative assembly would assign funds among and between the Commonwealth’s government agencies and departments according to its own spending priorities.

The implementation of this type of fiscal rule has several advantages. First, government spending is by definition limited to its structural income, minus the structural surplus target. Thus, government spending would be independent of short-term fluctuations in revenues caused by cyclical swings in economic activity and other financial vagaries that affect government revenues. Furthermore, this type of fiscal rule would force Puerto Rico to substantially improve its methodology for forecasting government revenues. According to Céspedes, Parrado, and Velasco, “forecasting mistakes, by definition, should be random and short-lived.” In Puerto Rico, revenue forecasts are biased towards the high side on a consistent basis.

Second, according to Velasco and Parrado, this type of fiscal rule, by limiting spending to permanent fiscal income, smoothens out government spending over the economic cycle. In essence, the government saves during upswings and dissaves during downturns. Therefore, the fiscal rule precludes both sizeable spending upswings when the economy is booming and drastic fiscal tightening when there is a substantial economic slowdown. “Hence, the growth of public expenditures becomes much more stable over time.”

Third, the fiscal rule we are proposing requires the Commonwealth to run a small surplus (to be determined as a percentage of GNP) over the life of the economic cycle. This requirement is necessary because (1) Puerto Rico’s debt burden is not sustainable over the long term; (2) the Commonwealth’s government faces potentially crippling contingent liabilities arising out of unfunded public pensions and expenses related to the government healthcare program; and (3) the Puerto Rico Government Development Bank, which provided significant deficit financing in the past, has ceased to exist.

(2) Overhaul of Public Financial Management (PFM) Systems

First, in terms of the budget formulation process, Puerto Rico needs to adopt strategic budgeting practices, namely: implementing performance-based budgeting, utilizing medium-term expenditure frameworks, reforming the current government procurement process that encourages rent-seeking by the private sector, and applying and executing the fiscal rule explained above.

Second, in terms of the budget approval process, the analytical capabilities of the legislative branch need to be substantially improved, perhaps by creating a legislative budget office with the capabilities to double-check and challenge economic and fiscal assumptions utilized by the executive in the preparation of the budget document.

Third, in terms of budget execution, the Commonwealth has to fix longstanding problems with its shambolic accounting, financial and fiscal controls, and with its financial reporting in general.

Furthermore, the agencies in charge of the Commonwealth’s public finances need to establish new procedures to coordinate policies among themselves and to upgrade their operational and execution capabilities, including the hiring of qualified human resources, establishing integrated financial management information systems, and improving internal control, internal audit, and real-time monitoring capabilities.

Finally, Puerto Rico should publish all its past-due audited financial statements as soon as possible. In addition, it has to implement whatever policies are necessary to assure the timely preparation and publication of these audited statements in the future.

Implementing these kinds of thorough transformations does not happen overnight. It is important, therefore, that the Puerto Rico Fiscal Responsibility Law set forth a specific calendar and sequence for implementing PFM reforms, as well as generally accepted indicators and benchmarks to measure progress.

Moreover, proper implementation of the FRL will also require the establishment of an autochthonous, lasting, and independent monitoring body that is embedded within the public island’s fiscal institutional landscape. One that is immune from partisan pressures but can effectively address political considerations and provide the needed technical expertise to address implementation challenges. Having a local commission that ultimately answers to the people of Puerto Rico, will not only provide political legitimacy to this exercise, but can also ensure that experiences and knowledge accumulated over time are effectively internalized within the larger bureaucratic infrastructure.

Finally, these transformations should occur as part of a broader institutional overhaul that also targets the various government agencies focused on establishing and implementing Puerto Rico’s economic development plans and policies.

Electronic Export Information

By Rosanna Torres – Director, Washington D.C. Office

A little over a month ago the U.S. Census Bureau published a notice of proposed rulemaking for the elimination of the Electronic Export Information filing requirement for shipments between the United States and Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While for the most part this notice has flown under the radar, the negative implications it poses over Puerto Rico’s economic data merits our attention.

Businesses that ship products to and from the U.S. and Puerto Rico may already be familiar with the extra requirement. For the benefit of those that are not, it is required by federal law that any shipment valued at over $2,500 or requiring an export license be reported to federal authorities. The information required – which includes data related to the shipper, product information, and destination – is known as Electronic Export Information (EEI) and is used for export monitoring and data processing.

Federal enforcement agencies use the data to prevent unauthorized shipments from being exported and the U.S. Census Bureau uses it for its calculation of monthly trade data. All of which begs the question: If this information has substantial effects on the soundness of economic data, then why is the federal government seeking to remove this requirement for Puerto Rico?

The Intricacies of the Election Process in the U.S.

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

This year things are complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic and a record number of voters who have already cast their ballots to avoid the crowd on Election Day. This combination could result in a strange election night, as the initial returns show President Trump ahead in key battleground states, only to see his lead evaporate as mail-in ballots, which tend to break heavily in favor of Democrats, are canvassed — a phenomenon called the “blue shift” by political scientists. So unless Biden runs the table on election night, which is possible but unlikely, we could be in for a long season of vote counting.

Under this scenario, we can expect both parties to slug it out in court, as challenges and counterchallenges are filed in key states over missing signatures and illegible postmarks. All the while the President keeps tweeting that the “Democrats are trying to steal the election!!!”. We can expect this because he has done it in the past. Look at what he tweeted on November 12, 2018, without any proof whatsoever:

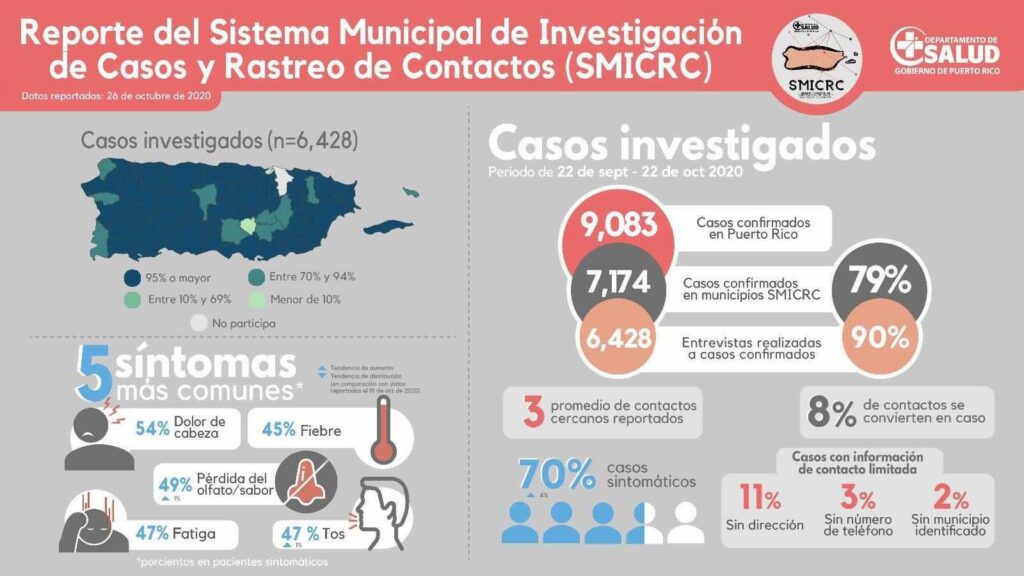

Data Snapshot

Tracking COVID-19 in Puerto Rico

Source: SMICRC, Department of Health

Contact tracing is a key tool in the battle against the coronavirus. Broadly speaking, the exercise focuses on communicating with infected people, asking them about their symptoms and when they started, who they were in close contact with, and taking the necessary steps to help patients and their contacts get tested and stay quarantined to prevent the virus from spreading further. Early in the pandemic, the Municipality of Villalba began a case tracking program that was later adopted in numerous municipalities and today is known as the Municipal System for Case Investigation and Contact Tracing (known as the “SMICRC” by its initials in Spanish). As the above graph indicates, the system has been able to interview 90% of the confirmed cases in the participating municipalities (San Juan does not participate in the effort) and has managed to identify an average of 3 close contacts for each confirmed case. The SMICRC publishes detailed reports on the implementation and the work carried out in the 77 participating municipalities that can be accessed via http://www.salud.gov.pr/Pages/Informe_de_Rastreo_de_Contactos.aspx.

On Our Radar...

![]() A Better Way to Think About the Future – “When it comes to anticipating the future, the United States is getting the worst of both worlds. It spends untold sums of money preparing yet still finds itself the victim of surprise — fundamentally ill equipped for defining events, such as the emergence of COVID-19. There is a better way, one that would allow the United States to make decisions based not on simplistic extrapolations of the past but on smart estimates of the future. It involves reconciling two approaches often seen to be at philosophical loggerheads: scenario planning and probabilistic forecasting” write J. Peter Scalic and Philip E. Fetlock in Foreign Affairs.

A Better Way to Think About the Future – “When it comes to anticipating the future, the United States is getting the worst of both worlds. It spends untold sums of money preparing yet still finds itself the victim of surprise — fundamentally ill equipped for defining events, such as the emergence of COVID-19. There is a better way, one that would allow the United States to make decisions based not on simplistic extrapolations of the past but on smart estimates of the future. It involves reconciling two approaches often seen to be at philosophical loggerheads: scenario planning and probabilistic forecasting” write J. Peter Scalic and Philip E. Fetlock in Foreign Affairs.

![]() What Happens if there is a COVID-19 Vaccine and No One Wants it? – “Today, the successful introduction of safe and effective vaccines to prevent infection with Covid-19 is increasingly in doubt, given the precipitous decline in public trust and confidence in science, health authorities, Washington, and vaccines. A leading cause is the White House’s contradictory and erratic messaging, falsehoods, and persistent efforts to manipulate the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The politicization of the Covid-19 response unfolds amid an already acutely polarized country and toxic electoral cycle. The decline in the public’s trust and confidence is coupled with a digital information environment that has become ever more polluted, chaotic, fragmented, and confused, providing a hospitable situation in which a variety of anti-vaccine forces can flourish.” That is why the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine have published this call to action.

What Happens if there is a COVID-19 Vaccine and No One Wants it? – “Today, the successful introduction of safe and effective vaccines to prevent infection with Covid-19 is increasingly in doubt, given the precipitous decline in public trust and confidence in science, health authorities, Washington, and vaccines. A leading cause is the White House’s contradictory and erratic messaging, falsehoods, and persistent efforts to manipulate the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The politicization of the Covid-19 response unfolds amid an already acutely polarized country and toxic electoral cycle. The decline in the public’s trust and confidence is coupled with a digital information environment that has become ever more polluted, chaotic, fragmented, and confused, providing a hospitable situation in which a variety of anti-vaccine forces can flourish.” That is why the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine have published this call to action.

![]() The Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment – “In March and April, as the coronavirus began tearing through the country, Americans lost as many jobs as they did during the Great Depression and the Great Recession combined — 22 million jobs that were there one minute and gone the next. For months, journalists at The New York Times and 11 other news outlets catalogued how the dual blows of joblessness and the pandemic were changing the lives of a dozen Americans.” These are their stories.

The Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment – “In March and April, as the coronavirus began tearing through the country, Americans lost as many jobs as they did during the Great Depression and the Great Recession combined — 22 million jobs that were there one minute and gone the next. For months, journalists at The New York Times and 11 other news outlets catalogued how the dual blows of joblessness and the pandemic were changing the lives of a dozen Americans.” These are their stories.