Published on February 11, 2021 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

President Biden’s proposed $1.9 trillion stimulus package is starting to draw some opposition from deficit and inflation hawks in the United States. Their argument is that the economy is in better shape than what was originally forecast last spring and therefore the new stimulus package will ignite inflation by increasing disposable income in excess of the existing gap between potential and actual output. Supporters of the Biden proposal argue that while it is true that previous economic stimulus has helped prop up millions of businesses and families, the fundamentals of the economy are still weak and the costs of a slow or stalled recovery far outweigh any potential costs of future inflation.

In our view, supporters of the Biden plan have the better arguments. Inflation has been below the Federal Reserve target for years now. Total employment is still some 10 million jobs below last spring’s level, the ranks of the long-term unemployed (six months or more) keep increasing, and millions of workers, especially women and minorities, have left the paid labor force (and therefore not counted as unemployed) to care for sick family members or to help their children with homeschooling.

In addition, hundreds of thousands of small and medium enterprises have closed for good, while the future of whole economic sectors, such as retail shopping, travel, leisure, and entertainment, looks wobbly. Finally, the ease with which the coronavirus is still spreading, the emergence of new strains, the slow start of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, and poor access to vaccines in large parts of the world, have complicated economic forecasts and made business and consumer behavior hard to predict.

In sum, it seems to us the downside risks of doing too little to stimulate the economy today significantly exceed the risks of hypothetical inflationary fires that may be stoked by President’s Biden stimulus package.

Stay the course, Mr. President.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Plan of Adjustment

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

The Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico (“FOMB”) announced yesterday that it “reached an agreement in principle with several creditor groups to lower Puerto Rico’s debt to sustainable levels after a successful mediation process.” As a result of that agreement, the FOMB asked the court to extend the deadline for filing an amended plan of adjustment (“POA”) until March 8, 2021. That POA would modify the terms and conditions of the central government’s debts with various groups of creditors. These debts include General Obligation bonds, bonds issued by the Public Buildings Authority, and obligations to various groups of unsecured creditors. In total, the POA would restructure approximately $35 billion in central government debt.

The previous FOMB offer to creditors sought to reduce this debt to approximately $11.9 billion, consisting of (1) $6 billion in cash; (2) $4.9 billion in new General Obligation bonds; and (3) $1 billion in the form of a Contingent Value Instrument (“CVI”). According to the FOMB, the combined recovery rate for all creditors would range from 31.3% (not including CVI payments) to 34.1% (including all CVI payments), although there is a wide range of variation among the different types of creditors. The terms of the new agreement have not been disclosed yet.

Now, the important point is that all this restructuring scaffolding is anchored in medium and long-term economic projections, which in turn are used to estimate the income available to the government and to calculate the primary surplus (the money that remains after paying the government’s operational expenses) that can be used to service restructured debt. According to media reports and documents published by the FOMB, some creditors are objecting to the FOMB’s economic projections because they consider them too pessimistic. This should not come as a surprise given the adversarial nature of the restructuring process. And also because making long-term economic and fiscal projections (20 years or more) is difficult during the best of times. And we are certainly not in the best of times.

Puerto Rico’s Unmet Needs

By Rosanna Torres – Director, Washington, D.C. Office

Puerto Rico has entered its fourth year of reconstruction. The amount of time that has gone by could suggest that recovery is fully underway. The reality on the ground, however, is very different.

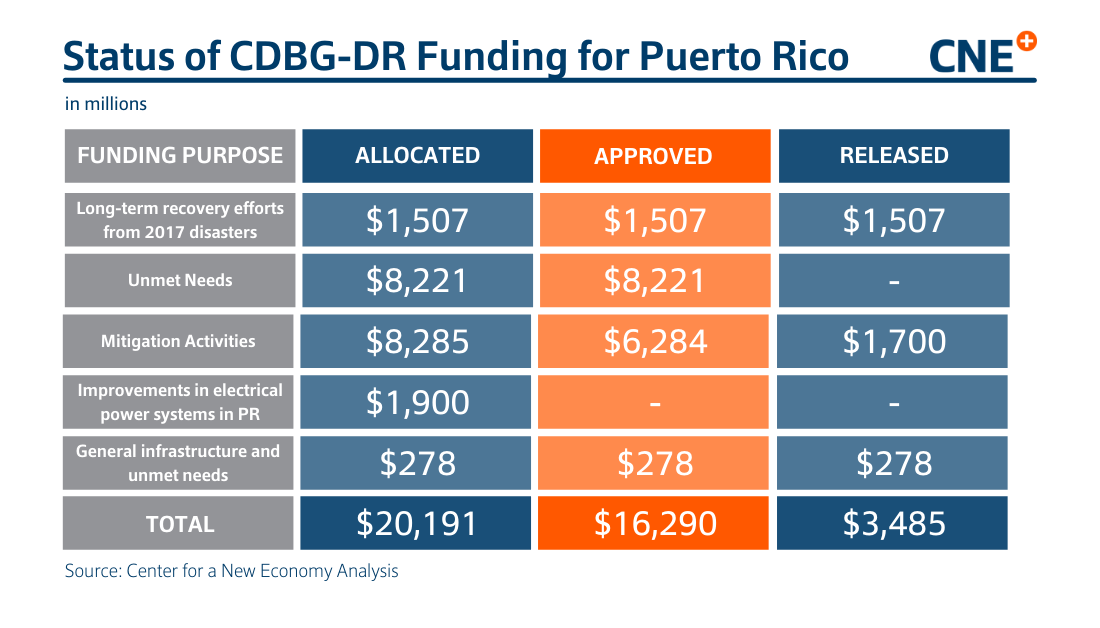

Despite the billions of dollars Congress has appropriated, the needs of the island largely remain unmet. There is little doubt that the slow pace in the release of funds has dampened Puerto Rico’s recovery efforts. Though part of the delay could be attributed to national disapproval over how Puerto Rico managed its finances in the past, that rhetoric has unfairly veered beyond its fiscal crisis and snowballed into the more toxic idea that Puerto Rico is incapable of running its own government. Capitalizing on that narrative, the Trump Administration appointed federal monitors in multiple agencies with unclear authorities, resulting in a highly bureaucratic and inefficient process that has hindered aid from reaching its intended recipients.

In light of the most recent funding approval from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), we take the opportunity to explain the amount of funding Puerto Rico has received as part of HUD’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program.

CNExplains

video in Spanish

By Jennifer Wolff, Ph.D. – Director, Madrid Policy Bureau

Which are the main global tendencies that Puerto Rico must take into account when framing an economic growth plan for the 21st century? The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered a series of global changes that will make it impossible for the island to rely on the same blueprint on which it has relied for the past decades.

On Our Radar...

![]() Housing and COVID-19 – Researchers Kay Jowers, Christopher Timmins, Nrupen Bhavsar, Qihui Hu, and Julia Marshall recently published an NBER working paper that found “that policies that limit evictions reduce COVID-19 infections by 3.8% and reduce deaths by 11%.” While “moratoria on utility disconnections reduce COVID-19 infections by 4.4% and mortality rates by 7.4%.” According to the authors “had such policies been in place across all counties (i.e., adopted as federal policy) from early March 2020 through the end of November 2020, policies that limit evictions could have reduced COVID-19 infections by 14.2% and deaths by 40.7%. For moratoria on utility disconnections, COVID-19 infections rates could have been reduced by 8.7% and deaths by 14.8%.”

Housing and COVID-19 – Researchers Kay Jowers, Christopher Timmins, Nrupen Bhavsar, Qihui Hu, and Julia Marshall recently published an NBER working paper that found “that policies that limit evictions reduce COVID-19 infections by 3.8% and reduce deaths by 11%.” While “moratoria on utility disconnections reduce COVID-19 infections by 4.4% and mortality rates by 7.4%.” According to the authors “had such policies been in place across all counties (i.e., adopted as federal policy) from early March 2020 through the end of November 2020, policies that limit evictions could have reduced COVID-19 infections by 14.2% and deaths by 40.7%. For moratoria on utility disconnections, COVID-19 infections rates could have been reduced by 8.7% and deaths by 14.8%.”

![]() Monopoly and Democracy – It was the great Louis D. Brandeis who wrote that “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” Professor Zephyr Teachout writes about the modern antitrust movement in this piece for Foreign Affairs.

Monopoly and Democracy – It was the great Louis D. Brandeis who wrote that “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” Professor Zephyr Teachout writes about the modern antitrust movement in this piece for Foreign Affairs.

![]() Minimum Wage – According to Annie Lowrey of The Atlantic “minimum wages have a way of screwing with economic intuition, and complicating the simple logic of supply and demand. The benefits of a $15 minimum would greatly outweigh the costs. More than that, new economic evidence suggests that those costs might be small ones anyway: Even in low-wage, low-density, low-cost-of-living parts of the country, a $15 minimum might not be a death knell for small businesses or a job killer for low-wage workers.”

Minimum Wage – According to Annie Lowrey of The Atlantic “minimum wages have a way of screwing with economic intuition, and complicating the simple logic of supply and demand. The benefits of a $15 minimum would greatly outweigh the costs. More than that, new economic evidence suggests that those costs might be small ones anyway: Even in low-wage, low-density, low-cost-of-living parts of the country, a $15 minimum might not be a death knell for small businesses or a job killer for low-wage workers.”