Center for a New Economy

SHARE

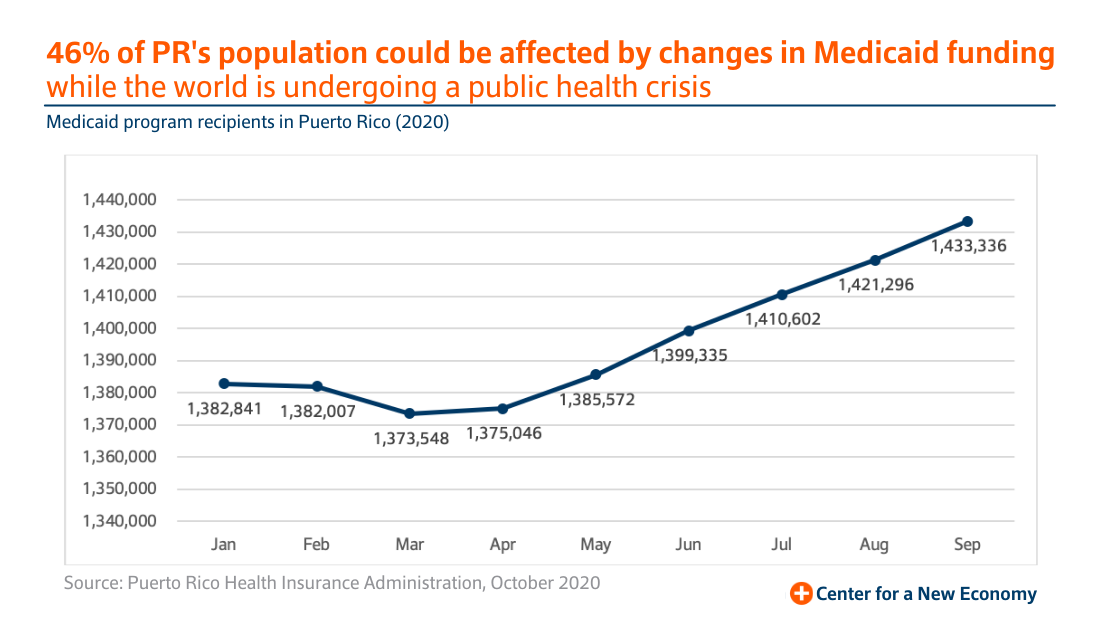

As we near the end of the federal fiscal year, Puerto Rico faces yet another potential shortage of funds to keep operating its healthcare system. The severity of the threat is very real. A drop in federal funding from $2.8 billion to approximately $400 million, a reduction of about 85%, could result in a failure to provide critical services to thousands of people, a reduction of the eligible population, and/or a drastic reduction of provider reimbursement rates, all of which may result in the flight of more primary care physicians and other health care providers from the island. With approximately 1.4 million Medicaid beneficiaries, about 46% of Puerto Rico’s population could be affected by the changes in funding at a time when the world is undergoing a public health crisis. Therefore, it is imperative to provide Puerto Rico with full federal Medicaid funding over time. This means allowing the federal share of the program, known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP), to be calculated for Puerto Rico on the basis of relative per-capita income (as it is in the states) and eliminating the arbitrary cap on funding set by federal law.

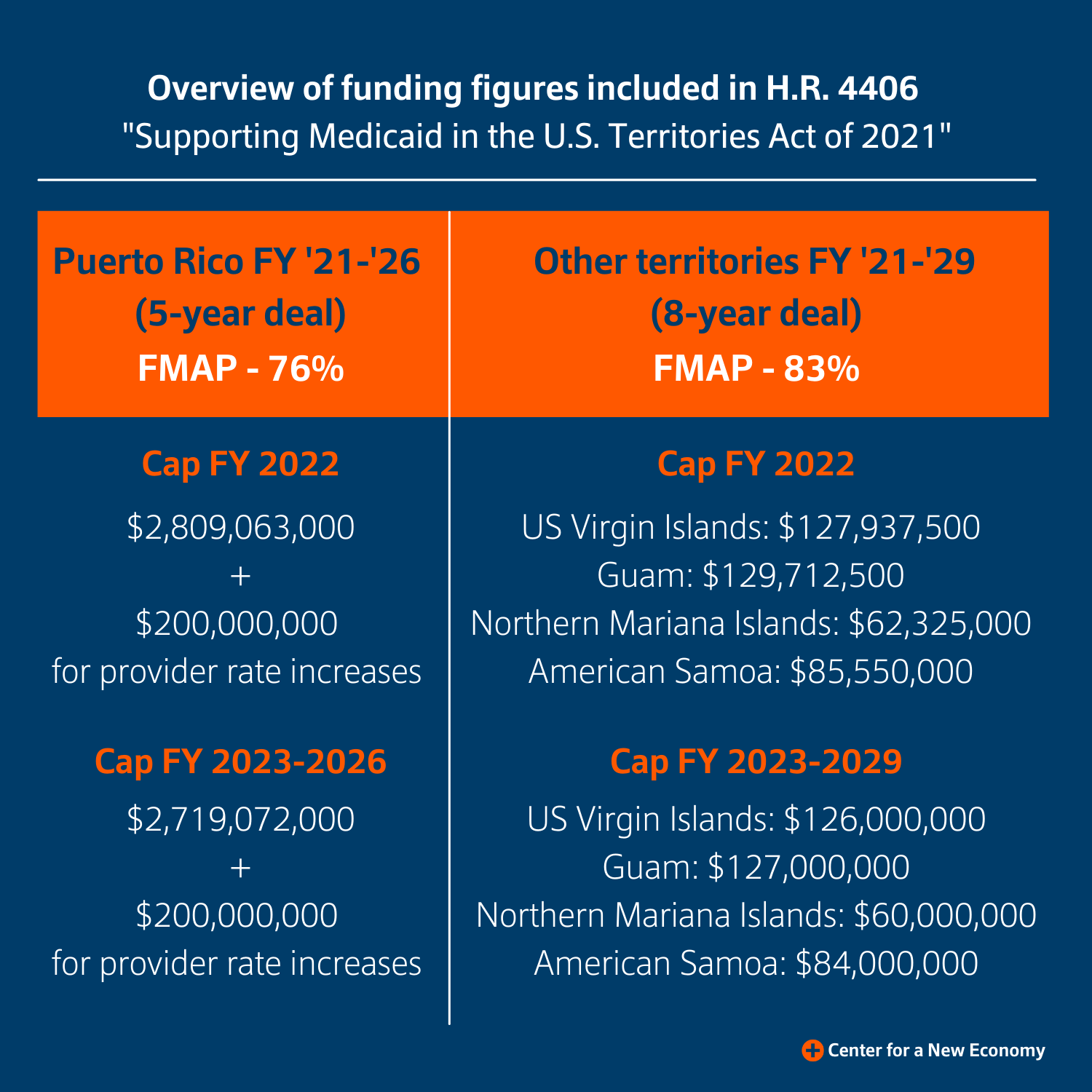

Concerned that a recovery package will not come through before the end of September, the House Energy and Commerce Committee started working with Republicans to strike a bipartisan deal on Medicaid funding. The bill, the “Supporting Medicaid in the U.S. Territories Act of 2021” (H.R. 4406), was marked up last week by the subcommittee on Health of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Below is a high-level overview of the topline figures. While the proposed bill ensures we avoid yet another funding cliff in the short term, it also, unfortunately, perpetuates long-standing inequities by essentially extending the currently inadequate funding levels for another five years. In this sense, recent coverage of the prospective Medicaid deal for Puerto Rico has been misleadingly portrayed as a big victory for the island by Puerto Rico’s leaders. In fact, though, when we consider the current political dynamic in Washington, this was a lost opportunity to obtain a more sustainable funding stream for Puerto Rico and the other territories, if not full parity with the United States.

The H.R. 4406 bill helps Puerto Rico avoid a short-term Medicaid funding cliff and provides some stability by setting forth clear funding levels for the next five years. However, the proposed five-year deal falls short of parity with the states, is not a permanent fix, and perpetuates the “separate and unequal” treatment of Medicaid beneficiaries in the territories, who are being told, once again, to accept a “good enough” deal.

Perhaps more important from a long-term policy perspective, the compromise set forth in H.R. 4406 represents the loss of a once-in-a-generation opportunity to end federal healthcare discrimination against the residents of the U.S. territories.

Early into its term, the Biden Administration stated its commitment to ensuring Puerto Rico is enabled to participate in the Medicaid program as other jurisdictions in the United States do. The President doubled down on that statement with the release of his first budget where he explicitly called for “eliminating Medicaid funding caps for Puerto Rico and other territories while aligning their matching rate with states.” Just two years ago, under a Republican majority, Puerto Rico received a generous two-year package. Now, while Democrats control the House, Senate, and the White House, Puerto Rico is coerced to settle for less generous treatment for a longer period of time. Making matters worse, the deal went through not despite but in the absence of a more forceful push from Puerto Rico officials. In their eagerness to promote an ideological agenda, officials have bartered the healthcare needs of low-income Puerto Ricans in favor of political expediency, by accepting the “second best” option once again. The White House now has an opportunity to push Congressional leaders for a more generous package.

Furthermore, the differences in year-out funding between Puerto Rico and the territories mean we’ll lose leverage when we face another funding cliff once again in five years, or sooner as the capped amount is not indexed to inflation. The amount of funding included in this five-year deal will likely fall short of what is needed to sustain the eligibility expansion achieved under the latest packages (essentially cutting people off healthcare during a pandemic) and Puerto Rico will be put in a bind when deciding how to make across the board reductions. This take-it-or-leave-it approach is morally reprehensible especially when it affects coverage for millions.