The current trends of technological change, climate risks, and social upheavals make the university as a social institution more relevant than ever. In view of this, what seems to be the dismantling of Puerto Rico’s public university system runs counter to the island’s needs and challenges basic common sense. One would never throw a vessel’s parts overboard when facing a tempest in open seas, but that seems to be what we are currently doing as a society with the University of Puerto Rico (UPR). It then seems pertinent to examine relevant case studies to understand how much the current assault on the UPR limits Puerto Rico’s capacity to face the challenges of the future.

Centers of innovation and regional development

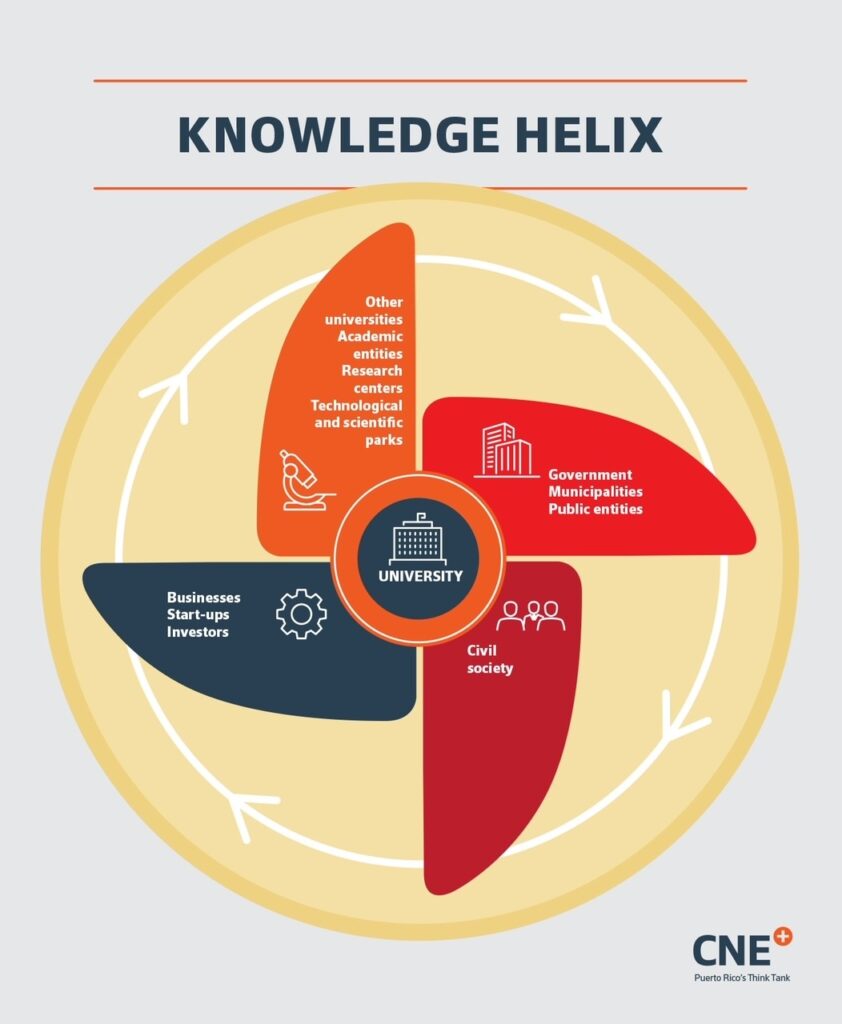

The increasing complexity of economic, environmental, and social problems has turned universities into crucial nodules of technological and social innovation. Their centrality, according to the European University Association, resides in their capacity to form human capital in new skills, produce research that creates novel knowledge and addresses complex problems and, increasingly, orchestrate regional innovation eco-systems. All of this happens in the context of the so-called knowledge economy, one which increasingly depends, not only on material inputs, capital, or labor, but on the application of knowledge to production processes. It is important to point out that scientific research encompasses not only the natural and physical sciences, but the social sciences as well: sociology, economics, psychology, history. In societies with less robust research and development (R+D) infrastructures like Puerto Rico, this catalytic role generally falls on public universities.

To illustrate the point: Germany has a solid R+D infrastructure in which research and innovation is produced not only in public and private universities but in governmental and private institutes, start-ups, and private companies. As much as 2/3 of the massive German annual investment of €105 billion in R+D originates in the private sector. This means that businesses and private institutes invest about $82 billion in R+D and are a vital component of the German innovation ecosystem. As a comparison, Puerto Rico’s Gross Domestic Product was about $71 billion in 2019, according to the local Planning Board. In contrast, 82% of scientific production in Spain is generated by universities, which are responsible for 40% of the county’s total investment in R+D. This space is primarily occupied by public universities, which dominate the STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Spain’s business ecosystem is fundamentally timid in terms of innovation: according to the most recent European Innovation Scoreboard, Spain barely has ¼ the number of top companies investing in R+D of the European median. This crucial role of public universities in R+D is particularly notable in the most underdeveloped regions of the country. For example, the University of Extremadura (UEx) – the only university in that autonomous community, one of Spain’s most disadvantaged – is responsible for almost half of the region’s total R+D investment and constitutes a key R+D pole for the region’s agro-alimentary sector. 93.5% of UEx’s students are from Extremadura, which means that the region’s public university is an important social and economic equalizer in a zone that has one of Spain’s lowest per capita incomes.

A growing body of literature highlights the capacity of universities to fuel regional economic development through “place-based Industrial Strategies”: in these cases, public investment in R+D channeled through universities enhances regional capabilities and fuels local economic specialization. Scholars have suggested, for example, that Great Britain capitalize on regional universities to foster artificial intelligence, clean energy, and medicine as economic sectors in geographical areas beyond the powerful economic nodule of London: Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. In Portugal, the Universidade do Minho – a public university – created TechMinho, an entity that links the campus to neighboring municipalities in the Vale do Ave and promotes the transfer to the region’s business ecosystem of the new technologies, products, and processes created in its classrooms and labs. Vale do Ave has historically been a textile-producing area and globalization has produced acute challenges for the zone. Thanks to the initiative fostered by the Universidade do Minho, students have created 530 businesses in the region, with an average volume of €2.2 million each (about $ 2.6 million) and a total labor force of 13,700. This accomplishment has not been achieved in a vacuum: it is part of a high-stakes gamble made by the Portuguese government, which channeled European Cohesion funds to the zone and endowed the region’s public universities with an important amount of monies for R+D. The Portuguese case is not exceptional: a recent study of 47 Spanish provinces developed by the University of Pécs in Hungary and the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya in Barcelona confirmed this relationship between public universities and the capacity of a region to attract Knowledge Intensive Business Services (KIBS). The impact of a university’s presence in a region was particularly notable in areas with low industrial concentration, like La Coruña or Pontevedra, in Galicia, or – it could be argued – like Puerto Rico.

The long-term costs of budgetary cuts

Despite all this evidence, it is common for governments to favor short-term goals in the midst of a fiscal or economic crisis, slashing instead public investment in research, something which produces results in the medium and long term. Spain’s Economic and Social Council has stated recently that the country is facing a worrisome reduction in the stock of public capital, both in terms of physical infrastructure and research-based knowledge, due to the dramatic reduction in public investment executed by successive governments as a reaction to the 2008 economic crisis. The Council is urging for this tendency to be reverted and suggests that public investment – including that in R+D – be used counter-cyclically, i.e., as a golden rule tied to the country’s fiscal rules, increasing public outlays in times of economic crisis. It is no coincidence that those countries that maintained their public investment in university education during the crisis – Austria, Belgium, Germany, Norway – are the ones with the top scores in the most recent European Innovation Scoreboard. If we use Spain’s example as a sort of canary-in-the-coal-mine for Puerto Rico – a warning of the future costs that today’s budgetary cuts to the UPR will bring– we would think that it makes sense to revert the current fiscal carnage and rebuild the island’s public university system for the future’s sake.