Table of Contents

Introduction

The topic of tax reform is back on the public agenda. This would be the fourth or fifth such “tax reform” (the exact number depends on how you define “tax reform”) in Puerto Rico since 2006. It cannot be denied that a thorough tax reform is needed. Puerto Rico has a tax system that no one consciously would have built from the ground up. It is unduly burdensome to administer and enforce; it is inequitable, along both horizontal and vertical dimensions; it oftentimes encourages the inefficient allocation of resources; and it discourages certain kinds of economic activity.

This tax system, originally designed in the 1950s when Puerto Rico was a small agricultural economy with a large labor surplus, little or no local capital, and an undeveloped local market, was initially tailored to promote economic development. In those days, efforts were focused on attracting foreign capital, matching it with the excess pool of local labor, and exporting the resulting products to the rest of the world. By most accounts, this model was relatively successful in jumpstarting the Puerto Rican economy.

The world today, however, is significantly different. With the passage of time, our tax system has evolved through the slow accretion of legislation into a complex web of preferential tax rates layered on top of multiple credits, deductions, exclusions, and exemptions that in many instances are not justified. In addition, it imposes high marginal rates on income, levying the heaviest burden on the middle class.

Thus, our tax system, which in theory should promote, or at least not hinder, economic growth by channeling financial resources to the productive sectors of the economy, has actually undermined our competitiveness; penalizes work, especially at the lower levels of the wage scale; encourages the informal sector; and hinders entrepreneurial activity. It should not surprise us that Puerto Rico’s growth rate has slowed down during the last 25 years, that close to half of its population lives in poverty, and that more than 50% of its people do not participate in the labor force.

The consensus in Puerto Rico is that a broad-based tax reform is long overdue. It is important to understand, however, that tax policy involves difficult trade-offs among various objectives, such as revenue generation, efficiency, simplicity, and equity. As a result, there is no single “correct” policy answer, each society has to determine the proper balance among and between these policy objectives.

Principles for a Tax Reform

We at the Center for a New Economy believe the following principles should guide any tax reform effort in Puerto Rico.

First, tax reform needs to be comprehensive. This means that all the elements of the tax system–personal and corporate income taxes, sales taxes, excise taxes, and property taxes–should be on the table. The objective is to look at the system as a whole and avoid the unintended effects and distortions produced by partial, half-baked, or stop-gap reforms.

Second, the tax system should provide adequate financing for government operations. This objective seems obvious, but many times those in charge of fiscal policy in Puerto Rico forget that, as Dr. Ramón Cao reminds us, “the basic justification for taxing is to pay for the services provided by the public sector.” In Puerto Rico, it is indisputable that the financing of state operations has been deficient during the last twenty or twenty-five years.

Third, expand the tax base. In plain English, this means eliminating some of those credits, deductions, exclusions, exemptions, and deferrals that have proliferated throughout the years. Enacting all those tax advantages has resulted in (1) an increase in the complexity of the tax code; (2) high marginal tax rates to compensate for the erosion of the tax base and (3) all sorts of distortions in the capital allocation process. Replacing the plethora of existing tax breaks with a universal refundable credit (for individuals) of 15 percent would go a long way towards eliminating these distortions.

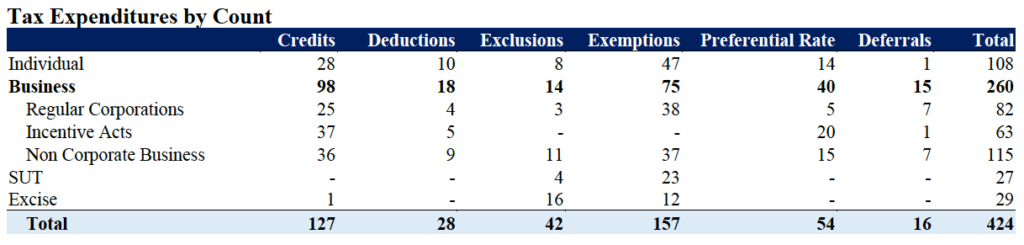

Source: FOMB, Letter to Department of Treasury: Tax Expenditures Report 2018, December 2, 2021, p. A-1.

As shown in the table above, the Puerto Rico Treasury Department identified 424 tax expenditures (essentially tax breaks) that were in effect during fiscal year 2018. The arguments in favor of enacting these kinds of tax preferences are that they generate “economic growth” or “create jobs”. However, we have not seen a credible and thorough cost/benefit or return on investment analysis of each of these tax preferences. Given Puerto Rico’s recent poor economic performance, it is highly unlikely these tax preferences are generating the real economic benefits claimed by their proponents.

Furthermore, we know from analyses in other jurisdictions that in many cases the alleged benefits of tax preferences fall well short of expectations. For example, a recent study by Professor Michael Thom of the Price School of Public Policy at the University of Southern California found that “in most cases motion picture incentive programs had no statistically significant employment impact.” A similar analysis should be undertaken for each of the 424 identified tax preferences and those which fail a cost/benefit analysis should be eliminated.

Fourth, lower marginal tax rates. This may sound counter-intuitive at first, but recent research, especially in the field of behavioral economics, shows that high marginal tax rates make it worthwhile for people to change their economic activities and to spend considerable resources to both legally avoid and unlawfully evade taxes. Lowering marginal tax rates reduces the incentive to engage in this kind of behavior and, if complemented with an expanded tax base, could actually lead to higher tax collections.

Fifth, simplify the system. Puerto Rico’s current tax code is insanely complicated, grossly unfair, and terribly inefficient. These defects hamper administration, compliance, and enforcement efforts, and, in the aggregate, they decrease the overall amount of tax revenues collected. A simpler tax code, if drafted correctly, would generate lower enforcement and compliance costs and higher tax collections.

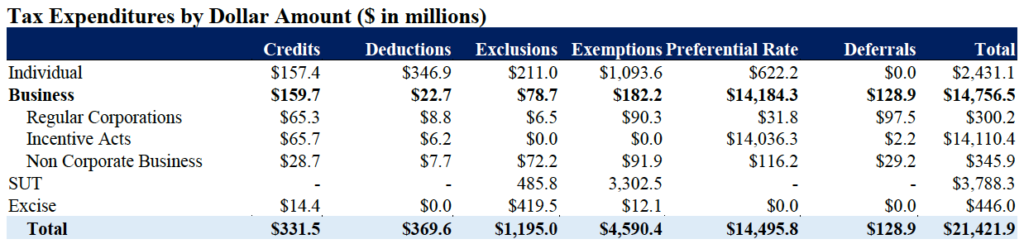

Source: FOMB, Letter to Department of Treasury: Tax Expenditures Report 2018, December 2, 2021, p. A-1.

As seen in the table above, the current medley of tax preferences costs the Puerto Rico Treasury approximately $21 billion, roughly twice the amount of the government’s general fund. While this figure should be taken with caution because the cost of each tax expenditure was estimated separately without taking into account behavioral and interaction effects, it does provide a rough approximation of the foregone revenue that otherwise would accrue to the state.

According to the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”), the “aggregate level of expenditures through the tax system in Puerto Rico dwarfs their use in international, national, and comparative U.S. state experiences. Puerto Rico is far too reliant on tax incentives as a tool for incentivizing development and the magnitude of incentives offered through the tax code is introducing heavy distortions and nonuniformity into the tax system and significantly contributes to the development of an unfriendly underlying tax regime.” The time is ripe to simplify the system.

Sixth, make the system fairer and more equitable. Fiscal equity can be analyzed in two dimensions. The impact of the tax system on (1) equity between the different sectors of society and (2) equity between generations.

The analysis of fiscal equity between the different social sectors, in turn, is divided into two parts: horizontal equity and vertical equity. According to Dr. Cao, the principle of horizontal equity, “or equal treatment of equals, states that the tax obligation must be the same for all people with the same ability to pay.”

On the other hand, “the principle of vertical equity, or different treatment of people in unequal positions, proposes that the tax liability for people with less capacity to pay should be less than that corresponding to people with greater capacity to pay taxes.”

The principle of intergenerational equity requires the government and corporations operating during the present generation to take into account the effects of their actions and decisions on future generations, for example, with respect to public goods or the use of nonrenewable resources.

Puerto Rico’s tax system fails across all fairness dimensions. To substantially increase horizontal equity, it is necessary to eliminate many of the tax preferences that have been legislated in a more or less random manner and whose effect is to increase inequality between people with the same ability to pay. Back in 2015, an analysis by KPMG identified 83 tax preferences for individuals, with an estimated cost to the Treasury of $1.138 billion. Of those 83, some 53 were used by fewer than 1,000 taxpayers.

The elimination of all or almost all of those preferences would have resulted in a significant increase in horizontal equity. Implementing that policy, though, is difficult because those relatively small groups that benefit from a tax preference have a strong incentive to organize and advocate for its continued existence, while the rest of the taxpayers are unorganized and the costs of acting collectively to pressure government probably exceed the individual benefits they may obtain from a rationalization of the tax code.

To increase vertical equity, it is necessary to avoid regressive taxes, which tend to disproportionately affect low-income households, university students, and the elderly. If it is not possible to avoid regressive taxes, such as Puerto Rico sales and use tax, then different mechanisms such as allowances and rebates could be implemented to increase vertical equity.

Finally, intergenerational equity used to be an important consideration when developing public policy in Puerto Rico. During the last two decades, though, these considerations have fallen by the wayside as policymakers have prioritized short-term goals at the expense of the long-term stability of Puerto Rico’s economy. It is necessary to retake an intergenerational perspective when making decisions about the allocation of scarce resources or the use of non-renewable resources.

Seventh, consider green taxes. These are taxes on activities that are harmful to the environment. They help reduce some of the most noxious effects of economic activity and provide an incentive to invest in environmentally friendly technology by forcing private sector actors to internalize the social costs of their pollution. In addition, they provide a new revenue stream for government. In the words of former Vice President Al Gore “we should tax what we burn, not what we earn.”

Conclusion

In sum, comprehensive tax reform involves multiple complicated trade-offs among revenue generation, efficiency, simplicity, and equity objectives. The art, and the difficulty, of tax reform lies in achieving a reasonable balance among these various considerations. At CNE, we will be keeping an eye on the tax reform that is currently being designed and will be ready to collaborate with policymakers to ensure that they succeed in this difficult balancing act.