NAP vs. SNAP: An Analysis on Federal Nutrition Assistance for Residents of Puerto Rico

Published on August 10, 2022 / Leer en español

Introduction

The cost of food has been in the headlines recently due to a set of intersecting crises. The still ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; the Russian invasion of Ukraine; supply chain disruptions; and natural disasters have combined to generate an overall spike in food prices. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “global food prices were 23 percent higher in May 2022 than they were a year earlier.”

Puerto Rico has not been exempted from this trend. According to the most recent release of the consumer price index for the island, the cost of “general foodstuffs” increased in June 2022 by 10.3% relative to the same month in 2021. We note this increase is probably underestimated due to problems with the construction of the price index for Puerto Rico. In any event, even if it is true that the rate of inflation for food in Puerto Rico is half the rate for the entire world, many households in Puerto Rico were already food insecure prior to the pandemic due to the relatively high cost of living in the island; little local production of basic dietary staples; the requirement to use costly U.S. flag vessels to transport food and other cargo from the U.S.; low wages; and high rates of poverty and income inequality.

This is the context, then, in which Puerto Rican and federal elected officials, members of the Biden administration, and civil society organizations have been advocating for a transition from the Nutrition Assistance Program (“NAP”) currently in effect in Puerto Rico to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (“SNAP”) currently operating in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories of Guam and the Virgin Islands.

As part of that advocacy effort, Congress ordered the Food and Nutrition Service (“FNS”) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) in 2021 to undertake an update of a 2010 study of the feasibility of implementing SNAP in Puerto Rico. The USDA, in turn, hired two consulting firms, Insight Policy Research and Mathematica, to carry out this update for FNS. The USDA released the final report of the Update to Feasibility Study of Implementing SNAP in Puerto Rico in July 2022 (the “Feasibility Study”).

For years, CNE has advocated for equal treatment in regards to federal programs such as Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, Earned Income Tax Credit, and a transition from NAP to SNAP. In this policy brief, we take a look at some of the most important findings of the Feasibility Study and analyze their implications for the full implementation of SNAP in Puerto Rico.

Nutritional Assistance in Puerto Rico

Federal nutrition assistance for residents of Puerto Rico began in November 1974 under the old Food Stamp Program (“FSP”). Initially and during the first eight years of the implementation of the FSP in Puerto Rico it functioned just like in the U.S.: all eligible participants received paper coupons which could then be used to purchase food items from certified food retailers on the island.

In 1982, Congress replaced the FSP in Puerto Rico with an annual block grant through the NAP. The annual block grant was initially capped at $825 million or 75% of the projected FSP costs for Puerto Rico in 1982. (Feasibility Study, p. 17) This cap was kept in place for the first five years of the program.

While the Feasibility Study claims this was done “in part to control nutrition assistance costs in Puerto Rico,” we disagree. There is no logical or rational relationship between the desire or necessity to cut the costs of any given program and the decision of whose benefits are cut, especially when it is decided to cut the benefits of a discrete group of beneficiaries. In this sense, it appears to us that the decision to implement the NAP in Puerto Rico as a capped block grant is yet another example in a long list of Congressional discrimination against territories based on a “racialized order of territorial exceptionalism” as documented by Andrew Hammond, professor of law at the University of Florida law school. (See Andrew Hammond, Territorial Exceptionalism and the American Welfare State, 119 MICH. L. REV. 1639 (2021))

Be that as it may, it appears that in exchange for lower funding and the implementation of the funding cap, Congress granted Puerto Rico greater flexibility in administering the program by shifting many regulatory decisions and functions to Puerto Rico. For example, when first implemented, NAP benefits were disbursed through paper checks that could be cashed at any food retailer, bank, or financial institution. However, on the negative side, eligibility requirements were stricter and benefit levels were reduced under NAP to adjust program costs to the lower funding level. Households with incomes of more than 85 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines (in July 1982) became ineligible, and benefit levels were reduced. The maximum NAP benefit for a household of four was $199, compared with the previous maximum of $221 under the FSP. (Feasibility Study, p. 17)

In 2001, the government of Puerto Rico began delivering benefits through an electronic benefit transfer system (“EBT”) and limited the amount that could be redeemed in cash to 25% of benefits. In 2015, Congress directed Puerto Rico to phase out the option of the 25% cash benefit and since the beginning of 2021, all benefits have been delivered using EBT cards that can be used only at authorized NAP retailers.

During FY2021, core block grant funding for the NAP was approximately $2 billion and provided benefits to 1.5 million low-income individuals. This core funding was supplemented with special appropriations in 2017, after Hurricane Maria, and in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For FY2022, the NAP block grant amount was increased by 23% to reflect similar changes to SNAP benefits due to a revision of the federal Thrifty Food Plan. As a result, block grant funding for FY2023 is expected to be approximately $2.6 billion. Finally, two bills are pending in Congress to fully transition Puerto Rico to SNAP.

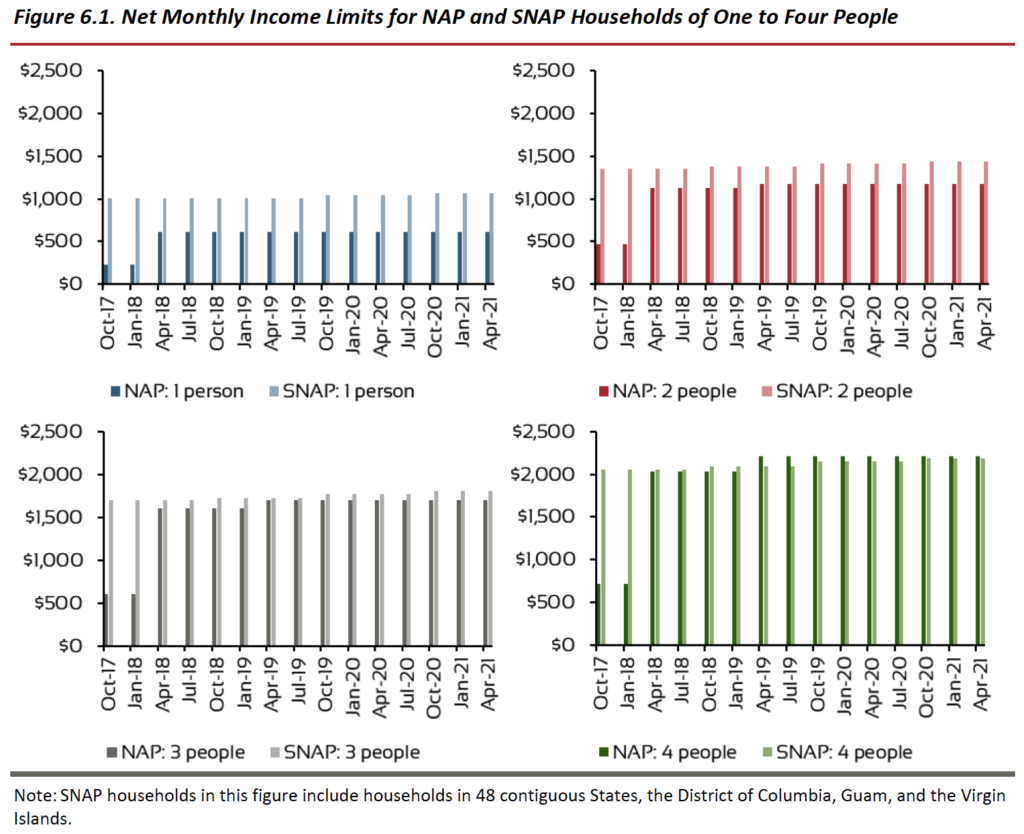

In general, the capped block grant structure of the NAP has generated discrepancies in eligibility criteria and benefit levels relative to SNAP. According to the Feasibility Study, NAP asset limits are higher than the SNAP asset limits but net income limits and maximum benefits levels are lower under NAP. For example, during FY2021, while the net income limit for a family of three was slightly lower for NAP than SNAP…smaller households [saw] a greater disparity in net income limits: A single-person household in Puerto Rico could have a monthly net income of up to $619 compared with $1,064 for SNAP. Alternatively, “larger households (of four or more) had higher net income limits for NAP than SNAP.”

Furthermore, “excluding adjustments to NAP and SNAP benefits resulting from COVID-19, the maximum NAP benefit in FY 2021 was 59 percent of the maximum SNAP benefit; this trend was similar for all household sizes.”(Feasibility Study, p. 18).

Transition to SNAP

The transition from NAP to SNAP would be a complicated process. It will be necessary, among other things,

- To enact federal legislation to authorize the operation of SNAP in Puerto Rico;

- To enact Puerto Rico legislation to conform with federal requirements for SNAP;

- For both the USDA and the government of Puerto Rico to issue new regulations for the operation of SNAP in Puerto Rico and to bring into alignment asset limits, income limits, work requirements, and other program parameters;

- To implement new quality control, compliance, and reporting requirements; and

- To provide for the operation of several components of SNAP that currently don’t operate in Puerto Rico, such as the SNAP Employment and Training program (“SNAP E&T”); the SNAP Nutritional Education program (“SNAP-Ed”); and Disaster SNAP.

In addition, Puerto Rico will have to hire and train new program officers (approximately 550 new hires just to process new applications), implement new procedures, and roll out new IT systems to manage the program.

According to the Feasibility Study, implementing SNAP in Puerto Rico could cost between $341 million and $426 million over an estimated 10-year implementation period; while administering SNAP after rollout would cost an estimated $249 million to $414 million, on an annual basis (FNS would cover approximately 54% of these costs).

The estimated cost of benefits issued to SNAP participants in Puerto Rico would be $4.5 billion annually, based on an average monthly SNAP participation of 861,000 households. (Feasibility Study, p. 155)

What to Expect Under SNAP in Puerto Rico

In general, a transition to SNAP in Puerto Rico is expected to increase the number of eligible individuals and households and raise the benefit levels of participants. However, some types of households may gain nutrition assistance eligibility and/or benefits under SNAP, while others may lose eligibility and/or benefits. The final distribution of winners and losers under SNAP will depend, in part, on policy decisions made by the government of Puerto Rico, and in part on the implementation of SNAP criteria instead of NAP criteria.

According to the Feasibility Study, the following are some of the effects that can be expected if SNAP is implemented in Puerto Rico:

- Asset Limits – In general, the NAP asset limits are higher than the SNAP asset limits. To be eligible for NAP, households with no members 60 or older may have no more than $5,000 in assets. Households with only members 60 or older have an asset limit of $15,000. (Feasibility Study, p. 31). While for SNAP, households with at least one member who is 60 or older or has a disability had an asset limit of $3,500. For all other households, the asset limit was $2,250. Thus, everything else being equal, the implementation of SNAP asset limits would result in a lower number of beneficiaries in Puerto Rico. However, the Feasibility Study states that this effect could be mitigated, at least in part, by adopting broad-based categorical eligibility (“BBCE”) rules. Under BBCE, states have been able to use asset and gross income limits for TANF noncash benefits to confer categorical eligibility for SNAP, for example, by eliminating asset limits or increasing the gross income limit up to 200% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines.

- Income Limits – According to the Feasibility Study, “The types and sources of income included in eligibility determination are generally similar for NAP and SNAP, including income of ineligible household members, but the exemptions, deductions, and income thresholds differ. The effect of a transition from NAP to SNAP on the overall amount deducted from gross income would vary by household and could affect various groups’ eligibility and benefit levels differently (e.g., older adults compared with parents with school-aged children).” (Feasibility Study, p. 36).

Source: Feasibility Study, p. 37.For example, as shown in the graph above, income limits under NAP are lower than SNAP’s for households of one to three people. So, everything else being equal, this would mean that a larger amount of smaller households in Puerto Rico would qualify for benefits under SNAP than under NAP.

- Work Requirements – Currently there are no work requirements under NAP. SNAP, however, has a general work requirement as well as a specific work requirement for Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents (“ABAWDs”). In general, “all SNAP participants aged 16–59 who do not meet Federal exemption criteria are required to register for work, participate in workfare or SNAP E&T if required by the State agency, accept a bona fide offer of employment, and not voluntarily quit or reduce hours of employment below a 30-hour work week.” In addition, “ABAWDs are required to work or participate in a work program 80 hours per month unless they receive discretionary exemptions or live in an area where the time limit is waived. ABAWDs who do not meet the ABAWD work requirement face a time limit on their benefit receipt of 3 months in a 36-month period.” (Feasibility Study, p. 31) The government of Puerto Rico would be required to implement these work requirements under SNAP. In most cases failure to comply with work requirements results in losing eligibility for SNAP. While a full discussion of work requirements is beyond the scope of this newsletter we note that (1) their application in the U.S. has been controversial; (2) their impact on labor force participation has been weak or negligible in many states; and (3) their implementation would require a significant investment on the part of the government of Puerto Rico in IT, data management, and additional human resources to adequately implement and enforce these requirements.

- Several Groups May Lose Eligibility or Receive Lower Benefits – Among these groups, the Feasibility Study highlights the following:

- Older adults or adults with disabilities who are allowed to form their own “household” for NAP purposes, even if they live and purchase and prepare food with others; in most cases, this would not be allowed under SNAP;

- Older adults participating in NAP currently receive an extra 20% of the maximum benefit for a one-person household, the payment of this additional amount, which is used mostly to compensate for the inapplicability of SSI to residents of Puerto Rico, would not be allowed under SNAP;

- Postsecondary students in Puerto Rico qualify for NAP benefits; under SNAP those enrolled half-time or more would be eligible to receive nutrition benefits only if they meet certain restrictive criteria;

- Households with modest assets may be ineligible for SNAP because asset limits under SNAP are considerably lower than under NAP; and

- NAP allows income deductions for older adults, people with disabilities, postsecondary students, farmers and farmworkers, and veterans that have no equivalent in SNAP; these groups may have a higher net income under the SNAP methodology and could therefore see their benefit levels or eligibility adversely affected.

In sum, the authors of the Feasibility Study conclude that “further research is needed to determine which NAP participants would be most likely to lose nutrition assistance benefits.”

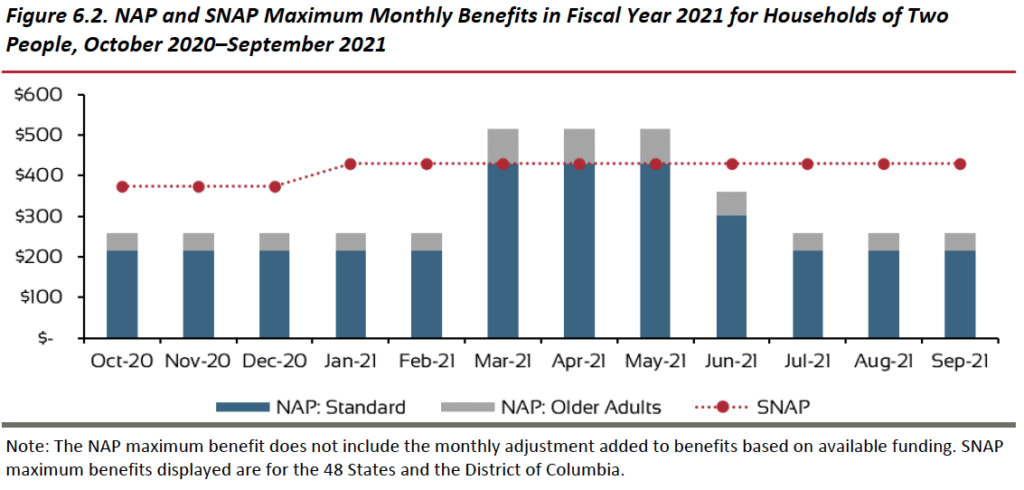

- Benefit Calculation – Maximum benefits under SNAP are based on the Thrifty Food Plan, while NAP maximum benefits are based on available funding and program participation. According to the Feasibility Study, “in 2021, in the absence of relief funding, the SNAP maximum benefit was 1.8–2.1 times higher than the NAP maximum benefit.” (Feasibility Study, p. 38) See chart below.

Source: Feasibility Study, p. 39.

- Estimated SNAP Participation in Puerto Rico – The authors of the Feasibility Study estimated SNAP participation in Puerto Rico using 2019 Puerto Rico Community Survey data in a microsimulation model applying both the standard federal SNAP rules and the BBCE rules. They found that under the standard SNAP rules the number of participating households would increase from an average of 723,435 under NAP to 838,418, an increase of 114,983 households, or 15.9%; the number of participating individuals would increase from an average of 1,330,902 to 1,449,360, an increase of 118,458 persons, or 8.9%; and the percentage of the total population in Puerto Rico covered by nutritional assistance would increase from 41.7% to 45.4%. Applying the BBCE rules they found that the number of participating households would increase from an average of 723,435 under NAP to 860,866, an increase of 137,431 households, or 19%; the number of participating individuals would increase from an average of 1,330,902 to 1,488,620, an increase of 157,718 persons, or 11.9%; and the percentage of the total population in Puerto Rico covered by nutritional assistance would increase from 41.7% to 46.6%.

Conclusion

So, what is the bottom line? As with many things in life, it’s complicated. In fact, the transition from NAP to SNAP could be a case study in the difficult trade-offs between costs and benefits, flexibility and standardization of program eligibility criteria, and discretionary and mandatory program administration rules and regulations, which policymakers face on a daily basis.

On the positive side of the ledger, we find: (1) funding for nutritional assistance would increase significantly under SNAP, from approximately $2.6 billion in FY2023 to $4.5 billion in FY2031; (2) the number of beneficiaries would increase between 9 and 12 percent (depending on the final set of rules adopted); (3) the maximum amount of benefits would increase, in some cases they may actually be double the amount currently available under NAP; and (4) the increased spending in nutrition expenditures would have a positive income multiplier effect on the local economy in both the food retail and the local agricultural sectors as well as a positive impact on overall employment.

On the other side of the ledger we need to take into account the following: (1) implementation costs could exceed $400 million dollars over a ten-year period, at a time when the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board has been implementing budget cuts across the government; (2) administering SNAP after rollout would cost an estimated $249 million to $414 million, on an annual basis (but FNS would cover approximately 54% of these costs); (3) some groups could lose eligibility for nutritional assistance or qualify only for lower benefits; and (4) the government of Puerto Rico would have to gear up for the implementation of several components of SNAP which currently don’t operate in Puerto Rico, such as the SNAP Employment and Training program (“SNAP E&T”); the SNAP Nutritional Education program (“SNAP-Ed”); and Disaster SNAP.

What about work requirements, are they a benefit or a cost? In a narrow monetary sense work requirements impose new programmatic costs as the government has to set up new employment and training programs as well as systems for monitoring compliance. In a broader sense, though, many advocates of work requirements argue that they produce a net social benefit as people who were otherwise unemployed become “useful” members of society. In practice, however, many nutritional assistance beneficiaries end up in lousy, dead-end jobs from which they cannot escape without losing benefits. This is what some scholars have called the “employment trap.”

The debate regarding the imposition of work requirements for recipients of public assistance is as old as the Bible itself (“Whoever will not work should not be allowed to eat”, 2 Thessalonians 3:10). And recurs throughout Western history, for example, in Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), the Elizabethan Poor Laws of 1601, and the first social insurance schemes in Bismarck’s Germany, all the way through the 1996 welfare reform in the U.S., and current debates regarding the federal Child Tax Credit.

While this newsletter is not the venue to fully address this debate, we do note that work requirements appear to be more effective in theory than in practice for several reasons. First, as we have mentioned, many people subject to these requirements end up in low-skill, low-wage jobs that provide little opportunity for advancement or for acquiring valuable skills. Second, studies of work requirements find that their economic impact has been meager at best, and statistically insignificant at worse. Third, some political philosophers argue that these kinds of requirements are an affront to and a violation of human dignity. In the end, we respectfully disagree with the authoritative St. Paul and prefer the gentler commands of the Man from Galilee, who advocated for feeding the hungry, giving water to the thirsty, and welcoming strangers. (Matthew 25:35)

Regardless of where the government stands in the debate over work requirements, it appears that the benefits of implementing SNAP in Puerto Rico outweigh the costs, provided that adequate measures are taken to try to protect, or reduce the impact on, those who may be negatively affected by the transition from NAP to SNAP. In a transition such as the one proposed, there will always be winners and losers, but we must try to minimize the negative consequences that particular groups would face.

However, there is another argument in favor of extending SNAP to Puerto Rico, beyond a purely utilitarian cost-benefit analysis. Ending Congressional discrimination against the residents of Puerto Rico in the application of nutritional assistance programs is a good in and of itself. There is just no rational basis for Congress’s arbitrary and capricious decision to exclude or limit the application of social safety net programs in the U.S. territories.

While some may have justified such treatment in the past using outdated racial and ethnic stereotypes such thinking should have no purchase in the 21st century.

People born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens by birth. That should be enough to warrant equal treatment.