Introduction

The Earned Income Tax Credit (“EITC”), enacted by Congress in 1975, is a tax credit available to working families in the United States whose incomes range from well below the federal poverty threshold to roughly double the poverty line.

The federal EITC helps low-income working families in two ways. First, since it is a credit, it reduces the federal tax liability of the taxpayer on a dollar for dollar basis. That is, each dollar of EITC reduces the taxpayer’s tax burden by a dollar. Second, unlike most federal tax credits, the taxpayer can claim as a refund any amount left over once its tax liability has been reduced to zero, a feature known as the “refundable” portion of the credit. This refundable portion of the EITC effectively works as a wage subsidy or supplement for low-income working families, which encourages participation in the formal workforce and reduces poverty.

Basic Economic Theory of the EITC

The EITC is tied to income earned from work, therefore, if properly designed, it should encourage people to increase the amount of hours worked and reduce the amount of hours dedicated to leisure. Intuitively, this outcome makes sense, the higher the effective wage, the more hours we expect an individual to work. However, economists have determined this intuitive theoretical outcome is not always realized in practice because an increase in the effective wage rate can operate through two different, contradictory mechanisms, known to economists as the income effect and the substitution effect.

The higher effective wage means that an individual can work fewer hours than he did before receiving the credit and still retain the same income level. This “income effect” induces the individual to work less and dedicate more hours to leisure. However, the higher effective wage also causes the relative price of leisure to increase, as the amount of forgone income associated with an extra hour of leisure increases. This “substitution effect” induces the individual to work more and dedicate fewer hours to leisure.

Policy Design

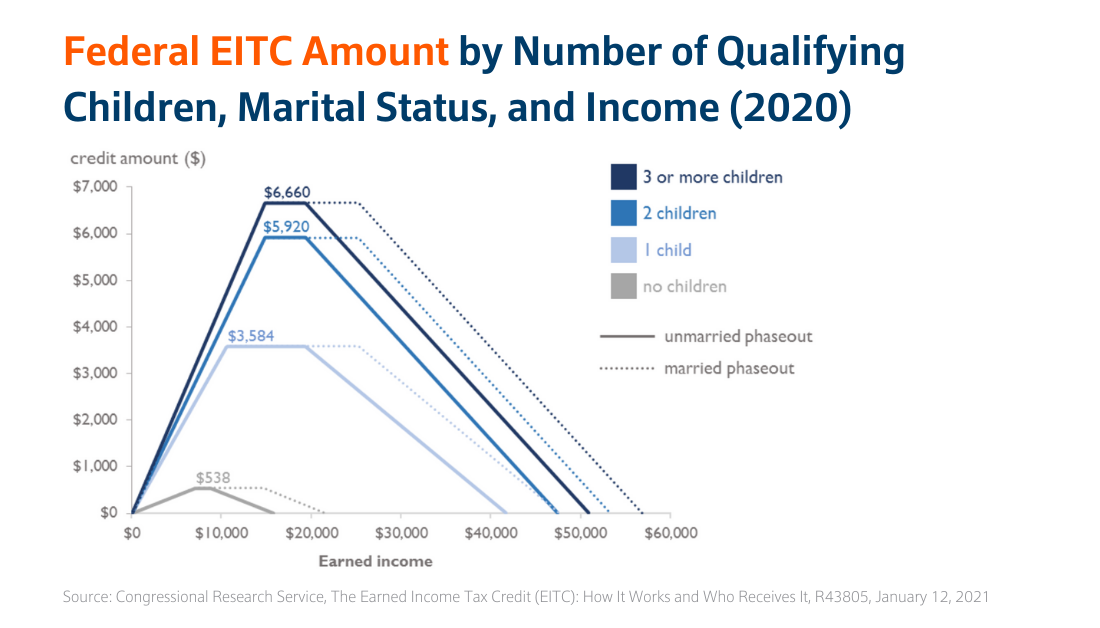

The challenge from a tax policy perspective is to design a program that will strengthen the substitution effect and weaken or overcome the income effect. The federal EITC has been designed with precisely these objectives in mind. As earned income increases, taxpayers qualify for an increasing EITC (known as the credit’s “phase-in” range) up to a maximum dollar amount. The maximum credit amount is available over a range of income (known as the “plateau” or “flat” range), after which the credit gradually phases down to zero (known as the credit’s “phase-out” range).

The figure above presents the phase-in, plateau, and phase-out ranges of the federal EITC for tax year 2020. In the phase-in region, the credit is phased in at a constant rate, which is 7.65 percent for taxpayers without children, 34 percent for those with one child, 40 percent for those with two children, and 45 percent for those with three or more children. In the flat region, taxpayers receive the maximum amount of the EITC benefit. In the phase-out region, the credit is phased out at a constant rate: childless filers face a 7.65 percent phase-out; one-child families lose 15.98 percent of each dollar earned due to the lost credit; and families with two or more children experience a 21.06 percent phase-out rate.

Several things stand out when we analyze the design of the federal EITC:

- First, the value of the credit increases at a relatively fast rate as earnings rise, especially in the case of families with very low earnings. This rapid rate of increase in the amount of the credit as the amount of earned income rises is a strong inducement to increase work and reduce leisure.

- Second, the credit amount reaches a plateau at a certain income level and stays constant until the taxpayer reaches an income level that falls within the phase-out range. This plateau range is an important design feature that further strengthens the substitution effect because, while the credit is no longer increasing, the taxpayer continues to be eligible for the maximum credit amount until her income reaches the statutory amount for the phase-out to begin.

- Third, the credit is structured to phase-out at a rate either equal to the phase-in rate, in the case of families with no children, or at a rate about half of the phase-in rate, in the case of families with one or more children. This phase-out structure weakens the negative income effect because the cost, in the form of a reduction in the credit, associated with increasing the amount of hours worked is lower than the benefits derived from work.

- Fourth, the total amount of the credit is a key variable in the design. In the United States, the EITC is designed to be a substantial wage supplement to low-income wage families. For example, a family with three or more children with an income of $16,000 would qualify for an EITC of $6,660, which is equal to 41 percent of its annual income. This is a significant wage supplement and a strong inducement to increasing the amount of hours dedicated to work.

- Finally, all income parameters in the phase-in, plateau, and phase-out range are indexed for inflation, so as to avoid the effects of “bracket creep” or movement into a higher tax bracket as a result of an earnings increase.

According to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (“CBPP”), in 2018, the EITC lifted about 5.6 million people out of poverty, including about 3 million children. They also estimate that the number of poor children would have been more than one-quarter higher without the EITC. Finally, according to their analysis, the credit reduced the severity of poverty for another 16.5 million people, including 6.1 million children.

Brief History of the EITC in Puerto Rico

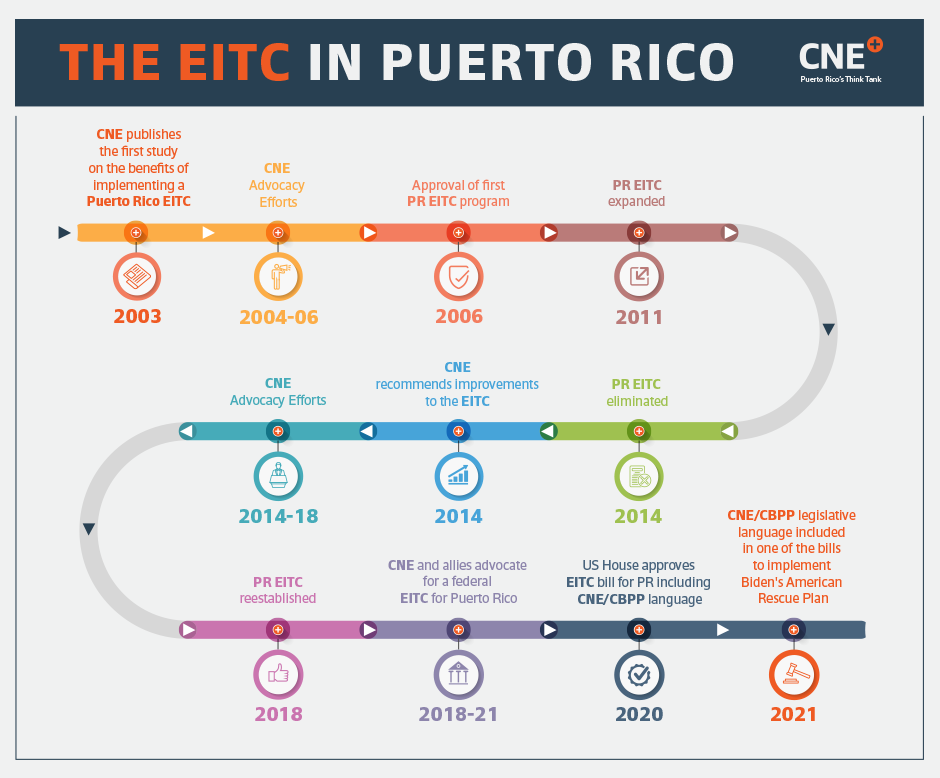

The federal EITC is generally not applicable to residents of Puerto Rico, depriving policymakers in Puerto Rico of an important social policy tool in the fight against poverty and unemployment. To remedy this situation, the CNE commissioned a study in 2003 that recommended the creation of a local EITC applicable to Puerto Rico residents who are otherwise precluded from claiming the federal EITC.

The Center’s advocacy paid off with the enactment of the 2006 Puerto Rico tax reform law, which created a Puerto Rico EITC, among other things. In our view, this was a significant step in the process of renewing and updating social welfare policy in Puerto Rico. However, the Puerto Rico EITC, as originally enacted, had several design defects that limited its effectiveness as a social welfare policy tool. Specifically, the phase-out rate was higher than the phase-in rate — when it should be the opposite — and the amount of the maximum credit was too low.

Some of these concerns were addressed when the Puerto Rico EITC was expanded as part of another tax reform bill enacted in 2011. Interestingly, and much like in the United States, politicians from all political persuasions supported Puerto Rico’s EITC. Even though the maximum credit was still relatively low at $450, data from the Puerto Rico Treasury Department shows that during tax year 2012 some 469,258 Puerto Rican tax filers claimed Earned Income Tax Credits in an aggregate amount of $124,304,299.

Unfortunately, the Puerto Rico EITC was eliminated to generate savings for the fiscal year 2015 budget. Before that decision was finalized, CNE issued numerous warnings about the negative effects its repeal would have on working families. CNE also maintained its advocacy and published (1) another study (jointly with the Urban Institute) in late 2014 setting forth the case for reinstating the Puerto Rico EITC and (2) a policy primer with Espacios Abiertos to inform the debate on this issue.

Finally, in December of 2018, Puerto Rico reinstated an earned income tax credit that costs approximately $204 million annually, and offers maximum credits between $300 and $2,000 depending on family size and configuration. While this expansion was a positive development, the Puerto Rico EITC, on its own, is small relative to the amount similar low-income households receive in the mainland.

Extending the Federal EITC to Puerto Rico

In Puerto Rico, where 44 percent of the population lives in poverty, it seems logical to extend the federal EITC to reduce poverty and inequality, boost incomes, and increase Puerto Rico’s chronically low labor force participation rate. Yet, for far too long Congress has refused to do so, relying on the specious argument that the EITC should not be extended to residents of Puerto Rico because they do not pay federal income taxes. While that argument may sound convincing at first and confirm the pre-existing biases that certain lawmakers already hold against the island, the truth is that the EITC was originally designed to offset the regressive effect of payroll taxes, which all Puerto Ricans working in the formal economy pay in full.

In early 2016, President Obama’s FY17 budget request included a proposal to extend federal funding to apply the earned income tax credit in Puerto Rico, to be managed by the Commonwealth. Despite the best intentions, this was primarily a perfunctory action that laid out the President’s view for a future Puerto Rico in his last year of office. At that time, the Obama administration budgeted $601 million to apply the federal EITC in FY2017, an amount that increased steadily to $734 million by FY2026, for a total cost of $6.642 billion over 10 years.

Back then, however, lawmakers could not agree on the adequate amount of funding for the federal government, much less on extending a new federal program to the island. Thus, the only economic policy achievement was to include a mandate in PROMESA to create a Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico. That Task Force released a report in December 2016 acknowledging the importance of the EITC as an effective policy tool to increase labor force participation and reduce poverty, but task force members ultimately conceded they could not reach consensus on extending the federal EITC to Puerto Rico.

The most recent $1.9 trillion COVID-19-related stimulus plan proposed by the Biden-Harris Administration includes meaningful tax credits for Puerto Rico, including a federal supplement to expand Puerto Rico’s local EITC for fiscal years 2021-2025.

However, this is not the first time this proposal makes it to the House Ways and Means Committee. In the summer of 2019, that committee approved Chairman Richard Neal’s “Economic Mobility Act of 2019”, H.R. 3300 and sent it to the full House for consideration. Tucked in that bill was a provision to match Puerto Rico’s local EITC by a proportion of 3 to 1. So, for example, if the local EITC has a cost of $200 million, the federal supplement could increase it up to $800 million annually by providing $600 million for Puerto Rico to increase the size of its own program, thereby improving the effectiveness of the Puerto Rico EITC as a pro-work, anti-poverty program.

This three-to-one formula is the product of years of well-documented research on the importance of the EITC for Puerto Rico. CNE, along with our partners and policy experts at the CBPP, worked on the design of the federal match since December 2018 as a workaround to the resistance of several lawmakers to extend a federal version of the EITC to the island. Make no mistake, though, the federal contribution is still far less than what the federal government provides Mississippi, the poorest state, which in 2017 claimed nearly $1.1 billion in federal EITC dollars. Yet, the federal supplement would ensure the credit’s sustainability, provide a significant income boost to low- and moderate-income families, and serve as a powerful incentive to draw workers from the informal economy into the formal economy. Our most recent with CBPP explains why the federal government should help Puerto Rico expand its new EITC program.

Last week, the House Ways and Means Committee again included language to match Puerto Rico’s local EITC by a proportion of 3 to 1, as part of President Biden’s American Rescue Plan. We trust the language adopted by the Ways and Means Committee will remain intact on the House floor, pass the Senate, and get signed into law, providing much-needed relief to low-income workers in Puerto Rico.