Policy Director

With contributions from:

Deepak Lamba-Nieves, Ph.D.

Research Director

Francis G. Torres

Senior Policy Analyst

DOWNLOAD

SHARE

Introduction

On September 18th, on the eve of the fifth anniversary of Hurricane María and as Puerto Rico was preparing to commemorate the lives lost and reflect on the destruction caused by one of the strongest storms ever seen around these latitudes, Mother Nature played one of her devious tricks on us by sending Hurricane Fiona on our way. Fiona hit the island as a category 1 hurricane with sustained winds of around 85 miles per hour. It is estimated the storm poured 1 trillion gallons of water on Puerto Rico over approximately 48 to 60 hours. The damage caused by flooding and the storm surge was serious, life-threatening in some instances, and widespread.

Fiona, therefore, laid bare once again the substantial vulnerability of Puerto Rican society to these kinds of events. For the impact of such a storm is not only a function of its force or strength, it is also a function of a given society’s pre-existing level of vulnerability. Puerto Rico was extremely vulnerable prior to Hurricane Fiona because only 30% of all permanent reconstruction work related to Hurricane María had started; thousands of people still lived in flood-prone areas; and basically, nothing had been done to strengthen the electric grid and other critical infrastructures or increase their resiliency. Given all of that, the key question to ask is: why five years after Hurricane María is the reconstruction process still at such an early stage?

The short answer, as we stressed three years ago, is that we have failed to address five key challenges to Puerto Rico’s recovery process, namely: (1) the lack of effective coordination among stakeholders, (2) poorly designed public participation platforms, (3) superficial transparency efforts, (4) the failure to implement adequate oversight mechanisms, and (5) the extremely slow outlay of recovery funds, especially for long-term permanent works.[1]

The damage caused by Hurricane Fiona will certainly add another layer of complexity on top of what was already a difficult and complicated effort. Ironically, though, it also provides us with an opportunity to rethink key plans and programs; identify existing deficiencies; and take effective actions to remediate them.

This Policy Brief will focus on the lack of effective coordination among the relevant stakeholders, set forth principles to guide the recovery process, present policy priorities for both the emergency response to Fiona and the ongoing reconstruction related to María, and suggest a mechanism for effective coordination among and between all the relevant parties.

A Failure to Communicate

Disaster recovery efforts are usually fraught with uncertainty and complexity at every level —economic, political, and emotional — and also stress-test the capacity of local governments and relief organizations to respond and advance reconstruction efforts in a prompt and equitable fashion. If the scale of the damage provoked by Hurricanes María and Fiona is considered, the complexities of Puerto Rico’s disaster recovery process become evident. All of Puerto Rico suffered massive damage.

Rebuilding devastated communities under a compressed timeframe, often juggling competing demands and problems that arise on a daily basis, and that are equally urgent, can prove challenging even in the best-prepared jurisdictions. After María, these stresses were magnified in Puerto Rico because it was not only managing a large-scale recovery process, it was also simultaneously going through the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. And now, of course, we have to address the damage caused by Hurricane Fiona.

In addition, at any given time in a post-disaster context, there are many actors working rapidly and independently, while relying on imperfect information, and their interactions and intersections are important throughout every stage of the process. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, post-disaster recovery experts Robert B. Olshansky and Laurie A. Johnson highlighted the importance of overcoming unanticipated problems: “Coordination is critical to recovery, due to many actors working in a compressed time environment and with constrained information flow. The only way to function effectively in a chaotic and uncertain environment is to provide information to actors systematically and coordinate with them regularly.”[2]

The government of Puerto Rico sought to address this issue when, back in October 2017, the Governor established the Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction and Resilience, or COR3, to oversee all disaster recovery efforts. The government set the expectation that this new agency would lead, coordinate and implement long-term recovery and reconstruction efforts.[3]

Key to that role was its capacity to coordinate efforts among all relevant actors. In the case of Puerto Rico, coordinating recovery and reconstruction efforts involves navigating a complex series of administrative frameworks which include a series of local and federal actors: the Puerto Rico Housing Department and numerous other Puerto Rico government agencies with key responsibilities in reconstruction efforts; FEMA and several other agencies of the federal government; municipal governments; local and foreign non-governmental organizations; hundreds of thousands of residents affected by the hurricane; and myriad external consultants. Thus, the María recovery process required coordination, first, among the relevant federal agencies; second, among and between those federal agencies and their counterparts in Puerto Rico; and third, among and between federal and state agencies on one side, and municipalities on the other.

Unfortunately, this coordination process has been flawed, at best. All this can sound awfully abstract at first so let’s use a concrete example. At a recent hearing of the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the U.S. House of Representatives, Ms. Anne Bink, Associate Administrator of the Office of Response and Recovery at FEMA, stated that “the largest ever public infrastructure project was obligated at nearly $9.5 billion to the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (“PREPA”), which will not just rebuild Puerto Rico’s power grid, but will build it back better.”[4]

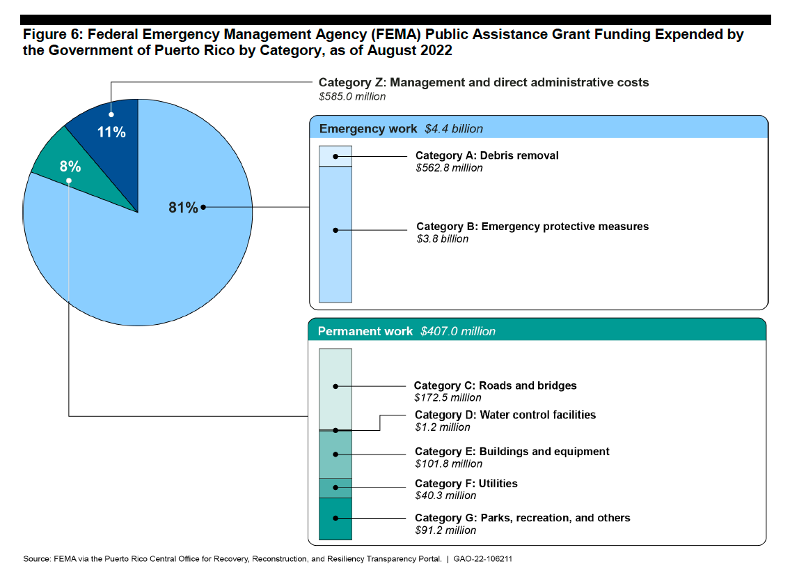

At the same hearing, however, Mr. Chris Currie, Director of Homeland Security and Justice at the United States Government Accountability Office (“GAO”), stressed that while a significant amount of money has been obligated to rebuild the electric grid, precious little has actually been spent. As shown in the chart below, only $40 million of the $9.5 billion obligated by FEMA has been spent as of August 2022 (see “Category F” in the chart below).[5]

Source: Statement of Chris Currie, September 15, 2022, p. 15, GAO-22-106211

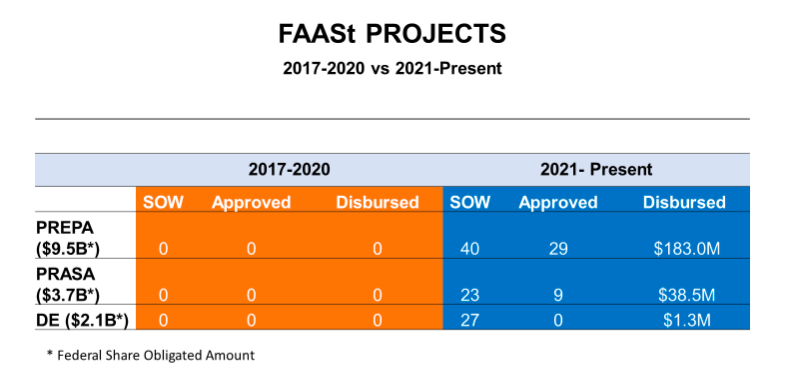

Minutes later, though, Mr. Manuel Laboy, Executive Director of the COR3, confidently stated that some 29 projects to repair some parts of the electric grid have been approved and a total of $183 million have been disbursed.[6]

Source: Statement of Hon. Manuel Laboy September 15, 2022, p. 26.

Source: Statement of Hon. Manuel Laboy September 15, 2022, p. 26.

Thus, an independent observer seeking to judge the progress to rebuild Puerto Rico’s grid would face a disparate set of figures. If the correct benchmark is the amount of money obligated to repair the grid, then it would appear that significant progress has been done. However, if, as many experts believe, the appropriate benchmark is how much money has actually been spent on projects to strengthen the grid, then progress has been painfully slow.[7]

Even if we agree that the spending rate is the right benchmark, we don’t know which figure is the correct amount: the GAO states that $40 million has been spent, while the COR3 states it has been $183 million. It is obvious to us, then, that the parties are not speaking the same language, or using the same definitions, or both. There is a clear failure to communicate, which in the final analysis is a failure of coordination.

In the case of the electric grid, there are at least two other factors that point to a large-scale coordination failure. First, it appears there is no agreement as to what is the plan to rebuild the grid. The Puerto Rico Energy Bureau argues that the grid has to be rebuilt in accordance with Puerto Rico’s Integrated Resource Plan (“IRP”), while PREPA appears to be working to implement a different plan called the “Ten-Year Modernization Plan” and LUMA seems to be working off its own “System Remediation Plan”. In addition, the federal Department of Energy is currently working on yet another grid modernization plan for Puerto Rico, which should be finalized by the end of 2023.

Please note that while the IRP sets the statutory requirements for the long-term (twenty years) modernization and operation of the grid, it was not drafted specifically for the María reconstruction and recovery process. On the other hand, the plans put forward by PREPA and LUMA assume a shorter timeframe and are proposals specifically made in connection with the ongoing reconstruction process. The DOE plan appears to be an attempt to both steer the grid reconstruction process and present a path forward for achieving 100% generation from renewables by 2050. Clearly, then, there is a coordination failure, because while these plans may partially overlap and intersect in certain aspects, they are based on different assumptions, have different implementation timelines, and, in the end, seek to achieve different objectives.

Second, as was pointed out by Mr. Currie during the September 15th hearing, LUMA and FEMA have had serious disagreements about

making repairs beyond the damages sustained during Hurricane María. Specifically, the private operator and FEMA disagree on which aspects of the agency’s proposed project the Public Assistance funding will cover. FEMA officials note that there are nuances involved in developing a complex project and ensuring it is eligible under federal laws and regulations.[8]

Finally, and this applies to all recovery projects, not only those related to the electric grid, the GAO found that oftentimes Puerto Rican government officials were not sure about how to proceed in accordance with FEMA policy because they did not know which set of guidelines were then currently in effect. Without access to relevant, up-to-date guidance, recovery stakeholders were exposed to the risk of acting in accordance with guidance that had been revised or replaced.[9]

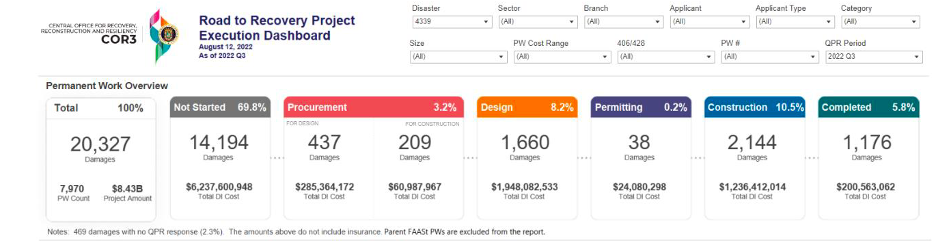

Source: Statement of Hon. Manuel Laboy September 15, 2022, p. 27

That last point would go a long way in explaining why, as shown in the chart above, only 5.8% of all permanent works projects have been completed as of August 2022.

In a similar fashion, coordination difficulties and bureaucratic hurdles have been at the center of significant delays in the approval and disbursement of funds assigned to complete municipal reconstruction projects. Local mayors argue that they confront sizeable delays (sometimes reaching 120 days) in the receipt of reimbursements for public works carried out. In addition, many municipalities on the island face serious budget constraints due to declining economic activity and austerity measures imposed by the FOMB.[10]

As a result, many cash-strapped municipalities have had to delay and at times halt much-needed reconstruction projects. Mr. Laboy has admitted that unnecessary bureaucratic processes and the substandard performance of certain multinational firms contracted to assist the COR3 in handling administrative procedures are a big part of the problem. [11] Thus, we should carefully analyze and diagnose the problem before making suggestions to impose quick fixes, without thinking through how they will interact with other processes affecting this massive reconstruction effort.

At this juncture of Puerto Rico’s recovery, the haze surrounding the status of the recovery process highlights the need to carefully define precise planning, coordination and implementation frameworks, and improve the flow of information. In other words, there is a need for an entity to comprehensively coordinate and manage Puerto Rico’s recovery.

Statement of Principles

As we stated five years ago, CNE believes that any entity or mechanism designed to manage the recovery process should comply with the following principles[12]:

- Coordination and Cooperation — The management structure for the recovery effort should serve as a forum to coordinate the spending of all federal recovery funding allocated to Puerto Rico, not only FEMA funds, and to provide for coordination first, among federal agencies; second, among and between federal agencies and their counterparts in Puerto Rico; and third, among and between federal and state agencies on one side, and municipalities on the other. It should also allow for the effective coordination of the work to be done by a plurality of groups and stakeholders working with different visions for the new Puerto Rico.

- Legitimacy — Provide a Forum for the Participation of the Democratically Elected Government of Puerto Rico: Any solution to this conflict has to provide a space for the effective and meaningful participation of the duly elected government of Puerto Rico. Otherwise, the reconstruction effort will be perceived as illegitimate and lack support from key political stakeholders on the island.

- Subsidiarity — This principle essentially requires that decisions that affect a certain community be taken at the government level closest to that community. According to the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church, the principle of subsidiarity is one of the most important principles of social philosophy:

“Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.”

Furthermore, “on the basis of this principle, all societies of a superior order must adopt attitudes of help (“subsidium”)—therefore of support, promotion, development—with respect to lower-order societies. In this way, intermediate social entities can properly perform the functions that fall to them without being required to hand them over unjustly to other social entities of a higher level, by which they will end up being absorbed and substituted, in the end seeing themselves denied their dignity and essential place.”[13]

The principle of subsidiarity is also defined in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union. “It aims to ensure that decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen and that constant checks are made to verify that action at the EU level is justified in light of the possibilities available at the national, regional, or local level. Specifically, it is the principle whereby the EU does not take action (except in the areas that fall within its exclusive competence) unless it is more effective than action taken at the national, state, or local level.”[14]

- Inclusiveness — Provide for the Participation of Stakeholders from the Private and the NGO Sector: Puerto Rico’s private sector and non-governmental organizations should be provided with a platform to express their visions and make their own proposals for a new Puerto Rico when the time comes to translate the rhetoric of resilience into concrete plans, architectural realities, political decisions, building priorities, and economic and financial costs. Otherwise, the whole effort will be bound to fail as the “new Puerto Rico” will inevitably not satisfy the expectations of the private sector and civil society and the net result will be increased migration to the mainland.

- Economic Impact and Strengthening the Local Economy — The entity(ies) in charge of rebuilding Puerto Rico should hire residents of Puerto Rico and local organizations on a priority basis to ensure that disaster survivors participate in recovery activities and directly benefit from recovery funds. This is especially important given Puerto Rico’s high poverty rate and low labor force participation.

Policy Priorities for the Recovery

In keeping with the principles above, CNE has identified three policy priorities to ensure that the next phase of the recovery process promotes equitable economic growth and enhances local capacity.

These priorities incorporate best practices from the recovery processes in New Orleans and New York in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, respectively, as well as lessons learned from the Hurricane María response through CNE’s ReImagina Puerto Rico project[15]

- The recovery requires a “bottom-up”, comprehensive, and unified planning effort, much like what was done in New Orleans after Katrina (via the Unified New Orleans Plan) and in the State of New York following Superstorm Sandy (via NY Rising). At present, the Government of Puerto Rico has centralized all planning efforts in the COR3 office. There are highly complicated issues, like land titling, mitigation vs. housing relocation, among others, that have to be addressed to avoid political pushback from municipalities and local communities. Moreover, if planning and implementation are performed in a piecemeal manner (bypassing certain localities or without the proper sequencing) coordination failures will occur and potentially lead to a longer and costlier reconstruction.

- Municipalities need to be engaged. Although the Commonwealth government has designed a centralized recovery and reconstruction process, largely controlled by the executive branch, the participation of municipal governments is essential for the success of these pursuits. Municipalities are the “first responders” in the emergency response period and play a fundamental role in the provision of basic services. They are also the government entity closest to local communities. However, not all municipalities are capable of administering reconstruction funds or managing large-scale projects. The key to engaging municipalities is knowing which ones have the capacity to lead, and which ones require capacity building. Nonetheless, the recovery and reconstruction processes offer numerous opportunities for municipalities to devise and implement creative and cost-saving solutions.

- Island contractors need to be prioritized in the recovery process. Traditionally, federal disaster response has been understood as the “silver lining” that stems from a catastrophic event, given the millions of U.S. government dollars that are pumped into the local economy. Federal funding for recovery, according to this logic, will have a multiplier effect that could potentially steer Puerto Rico’s economic growth rate into positive territory. Although much of the optimism is tied to potential investments funded by the federal government in Puerto Rico, the bulk of federal expenditures for both relief and recovery efforts is not flowing into Puerto Rico-based businesses, and therefore such spending has not been very effective in stimulating the local economy. As it stands the recovery process, is neither fostering local hiring nor focusing on high-impact industrial sectors. CNE has begun to analyze the contracting data, with a focus on key agencies like the DHS, USDA, and USACE, amongst others. Hiring a greater number of local firms for a longer period of time could also provide learning and capacity-building opportunities for many of these actors, which could improve their ability to address future natural events in Puerto Rico or elsewhere in the mainland U.S. Thus, local firms should be given priority and mainland firms should be compelled to hire local subcontractors when appropriate.

A Proposal to Implement Principles and Policy Priorities for the Reconstruction

One way to implement these principles and priorities would be by creating an entity similar to the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, which was created by President Obama pursuant to Executive Order 13632 of December 7, 2012 (the “Sandy Executive Order”). The Sandy Executive Order:

- Created a Task Force chaired by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. In addition, it included the head of 23 other federal executive departments, agencies, and offices involved in the recovery process.

- Stated that the principal function of the Task Force was to provide the coordination necessary to support the rebuilding of the area affected by Hurricane Sandy, including “working closely with FEMA within the scope of the National Disaster Recovery Framework (“NDRF”).”

- Ordered the Task Force to “identify and work to remove obstacles to resilient rebuilding in a manner that addresses existing and future risks and vulnerabilities and promotes the long-term sustainability of communities and ecosystems”.

- Mandated that the Task Force “coordinate with entities in the affected region in efforts to: (i) ensure the prompt and orderly transition of affected individuals and families into safe and sanitary long-term housing; (ii) plan for the rebuilding of critical infrastructure damaged by Hurricane Sandy in a manner that accounts for current vulnerabilities to extreme weather events and increases community and regional resilience in responding to future impacts; (iii) support the strengthening of the economy; and (iv) understand current vulnerabilities and future risks from extreme weather events, and identify resources and authorities that can contribute to strengthening community and regional resilience as critical infrastructure is rebuilt and ecosystem functions are restored”.

- Required the Task Force to “engage local stakeholders, communities, the public, Members of Congress, and other officials throughout the areas affected by Hurricane Sandy to ensure that all parties have an opportunity to share their needs and viewpoints to inform the work of the Task Force”.

- Authorized the Chair to create an “Advisory Group to advise the Task Force and invite individuals to participate in it. Participants shall be elected State, local, and tribal officials and may include Governors, Mayors, County Executives, tribal elected officials, and other elected officials from the affected region as the Chair deems appropriate.”

- Provided for the Task Force to have a staff, “headed by an Executive Director, which shall provide support for the functions of the Task Force.”

- Allowed the Task Force to “establish technical working groups of Task Force members, their representatives, and invited Advisory Group members and elected officials, or their designated employees, as necessary to provide advice in support of their function.”

In our view, if a similar entity were to be created to coordinate the recovery process for Hurricanes María and Fiona, it would comply with the principles and policy priorities set forth above because:

- It would have an explicit mandate to coordinate recovery efforts among and between the federal agencies and among and between the federal government and the government of Puerto Rico.

- It would provide for the inclusion of Puerto Rican elected officials at all levels and their representatives, including the COR3, through an advisory group.

- It would promote subsidiarity and inclusiveness by engaging local stakeholders, municipalities, community organizations, NGOs active in Puerto Rico, and business leaders.

- And it would strengthen the local economy by ensuring that residents of Puerto Rico and local business enterprises are hired on a priority basis.

Notice that we are advocating for a very specific and particular kind of coordination mechanism that satisfies a discrete set of procedural, equity, and inclusion principles. CNE would not support any similar entity that does not satisfy the principles or fails to implement the policy priorities set forth herein.

For the sake of clarity and the avoidance of any doubt, we are not advocating for the “federalization of the recovery process” (whatever that may mean); the appointment of a “recovery czar” in the White House; or the “takeover” of the recovery process by the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board.

To achieve a just recovery, Puerto Rico needs coordination and oversight that works — not punitive measures. Successful recoveries require ongoing deliberation and dialogue between all involved stakeholders to ensure that all relevant perspectives are heard and have a chance to influence the process. Moreover, appointing a “recovery czar” or “federalizing” the process would not provide opportunities for local capacity-building.

When an isolated office dictates the recovery process from the top down, the opportunity for local actors to be involved in decision-making and learn key lessons in recovery management is lost. Centralizing the recovery also centralizes information flows, and can pose a threat to accountability and transparency if the newly created entity is not answerable to other actors involved in the recovery.

Conclusion

Hurricane Fiona has opened a window of opportunity for government officials in Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico to streamline the ongoing Hurricane María recovery process and to correctly frame the Hurricane Fiona recovery. Throughout this Policy Brief we have emphasized the need for: (1) creating a distinct recovery coordination mechanism; (2) implementing specific principles that allow for reflection, flexibility, and adaptability; and (3) executing some key policy priorities to promote equitable economic growth and enhancing local capacity.

If properly designed and implemented the proposed mechanism would facilitate effective coordination among stakeholders at different levels of government, insure adequate public participation in the planning and oversight process, provide greater transparency and accountability in the project selection phase and the use of funds, and speed up the outlay of recovery funds.

To move forward, Puerto Rico must seize this opportunity to evaluate the hurricane recovery process and modify the existing recovery governance framework. In the final analysis, every disaster is “a time of desperate loss, yet also a time of distinct possibility.”[16] Let’s make the most of this time of possibility.

Endnotes

[1] Center for a New Economy, Oversight that Works, August 2019, available at https://grupocne.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/CNE-Policy-Memo-Oversight-That-Works.pdf

[2] Olshansky, R. B., & Johnson, L. A. (2010). Clear as Mud: Planning for the Rebuilding of New Orleans, Washington, DC: American Planning Association.

[3] See Executive Order OE-2017-65

[4] Statement of Anne Bink before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the U.S. House of Representatives, “Recovery Update: Status of FEMA Recovery Efforts in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands 5 Years After Hurricanes Irma and Maria”, September 15, 2022, p. 2.

[5] Statement of Chris Currie before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the U.S. House of Representatives, “Recovery Update: Status of FEMA Recovery Efforts in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands 5 Years After Hurricanes Irma and Maria”, September 15, 2022, p. 15, GAO-22-106211.

[6] Statement of Hon. Manuel Laboy before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the U.S. House of Representatives, “Recovery Update: Status of FEMA Recovery Efforts in Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands 5 Years After Hurricanes Irma and Maria”, September 15, 2022, p. 26.

[7] According to Mr. Currie’s statement “An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability of the government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received. For the purposes of this statement, obligations represent the amount of grant funding FEMA provided through the Public Assistance program and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program for specific projects in Puerto Rico and the USVI. An expenditure is an amount paid by federal agencies, by cash or cash equivalent, during the fiscal year to liquidate government obligations. For the purposes of this statement, an expenditure represents the actual spending by the government of Puerto Rico government or the USVI government of money obligated by the federal government.”

[8] Statement of Chris Currie, September 15, 2022, p. 19, GAO-22-106211

[9] Id. at p. 12.

[10] Many FEMA programs work on a reimbursement basis, which presents a difficulty to many municipalities and government agencies that may not have the required cash flow available to finance long-term permanent work projects.

[11] See: “Truenan los alcaldes por situaciones con desembolso para la reconstrucción en los municipios”, Primera Hora, February 1, 2022; “Nuevo director de COR3 acepta responsabilidad en atrasos de los fondos de recuperación a municipios”, Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, February 12, 2021.

[12] Sergio M. Marxuach, Expediting the Recovery Process: A Proposal to Create a Puerto Rico Development Authority, Center for a New Economy, December 2017, available at https://grupocne.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PRDA-Policy-Brief.pdf

[13] Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church, 186; see also, Leo XIII, Encyclical Letter Rerum Novarum (1892); Pius XI Encyclical Letter Quadragesimo Anno (1931); John Paul II Encyclical Letter Centesimus Annus (1991); and Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1882 and 1883.

[14] See Lisbon Treaty, Article 5, (2007) (ratified 2009) and http://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/glossary/subsidiarity.html

[15] The goal of Reimagina Puerto Rico was to devise a process whereby the people of Puerto Rico could effectively participate in defining recovery priorities. Through a wide ranging and inclusive public participation effort—which included 77 meetings and activities with over 700 participants in island communities and the diaspora—both specialists and community stakeholders identified close to 500 recovery opportunities. The top ideas are contained in a detailed report recently produced by Reimagina, which provides 97 priority actions across six key sectors. Funding from the Ford Foundation, Open Societies Foundation and technical assistance from the 100 Resilient Cities project were instrumental in these efforts.

[16] Lynne B. Sagalyn, Power at Ground Zero: Politics, Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan, (Oxford, 2016), p. 5.