El impacto de los alquileres a corto plazo en Puerto Rico: 2014 – 2020

Publicado el 12 de diciembre de 2022 / Read in English

AUTORES

Fellow de Investigación

Director de Investigación

Enrique Figueroa Grillasca

Asistente de Investigación

Ysatis A. Santiago Venegas

Asistente de Investigación

DESCARGUE

COMPARTA

Resumen

Puerto Rico atraviesa por una crisis de vivienda, caracterizada por una escasez de unidades asequibles, aumentos en los costos de vivienda, una proporción significativa y en aumento de inquilinos con rentas onerosas y más de 300,000 unidades perjudicadas por tormentas, huracanes y terremotos desde el 2017. En medio de este escenario sombrío de la vivienda, existe una controversia aún sin resolverse sobre el crecimiento de alquileres a corto plazo (ACP) en Puerto Rico, la cual se ha ido intensificando con el tiempo.

Por un lado, los ACP, particularmente las plataformas como Airbnb, han sido catalogados como un motor de desarrollo económico local en un archipiélago asediado por una larga crisis económica y fiscal. Por otro lado, varias comunidades y organizaciones de base comunitaria en Puerto Rico han argumentado, usualmente con evidencia concreta, que la expansión rápida de los ACP ha fomentado la gentrificación y el desplazamiento residencial en sus comunidades.

Este informe provee un análisis detallado de la actividad de ACP en Puerto Rico y atiende varios de los reclamos hechos por distintos grupos, a través de un análisis que se enfoca en: la efectividad de los ACP en proveer oportunidades económicas para dueños de hogares necesitados; y los efectos de los ACP sobre los mercados y la asequibilidad de la vivienda. También llevamos a cabo una revisión de la literatura sobre posibles regulaciones para los ACP para entender mejor cómo políticas específicas pueden ayudar a atender los impactos a los mercados de vivienda.

Nuestros hallazgos hacen eco de las tendencias evidenciadas alrededor del mundo. Específicamente, nuestro análisis muestra lo siguiente:

- El mercado de los ACP está cada vez más concentrado, profesionalizado y comercializado, con anfitriones que tienen múltiples espacios registrados para este tipo de alquiler, quienes acumulan una cantidad desproporcional de propiedades e ingresos.

- El registro de nuevas unidades en las plataformas de ACP responde a las temporadas turísticas de Puerto Rico, pero también a los desastres, dado que el huracán María y la pandemia de COVID-19 causaron aumentos y reducciones súbitas en la creación diaria de unidades listadas.

- Los ACP afectan sustancialmente la asequibilidad de la vivienda, lo cual puede llevar a la gentrificación:

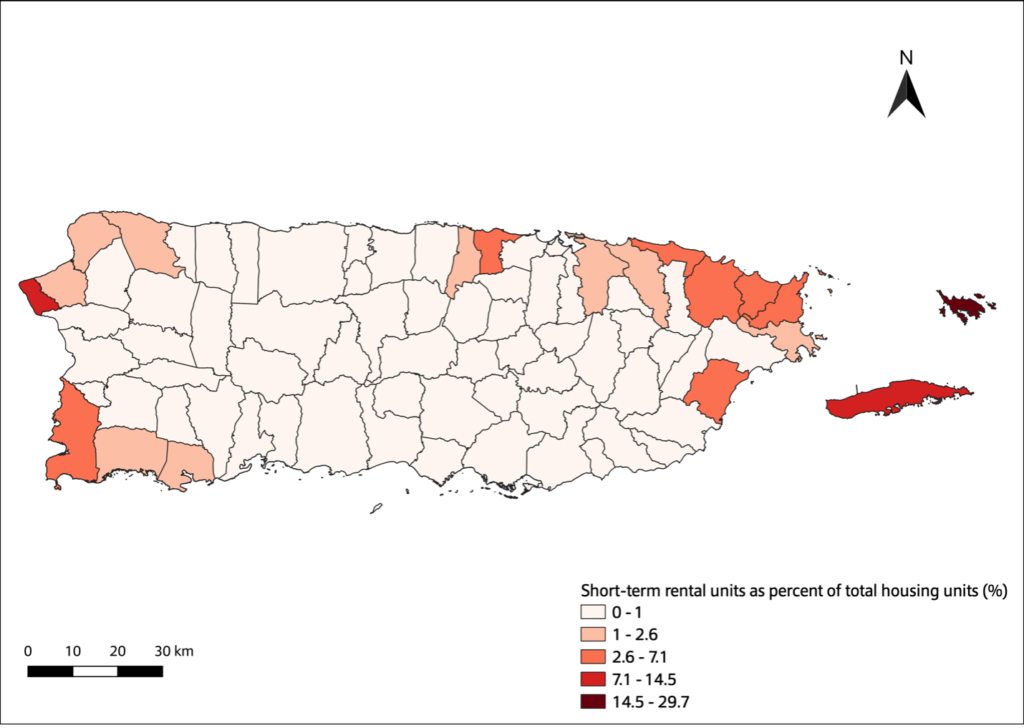

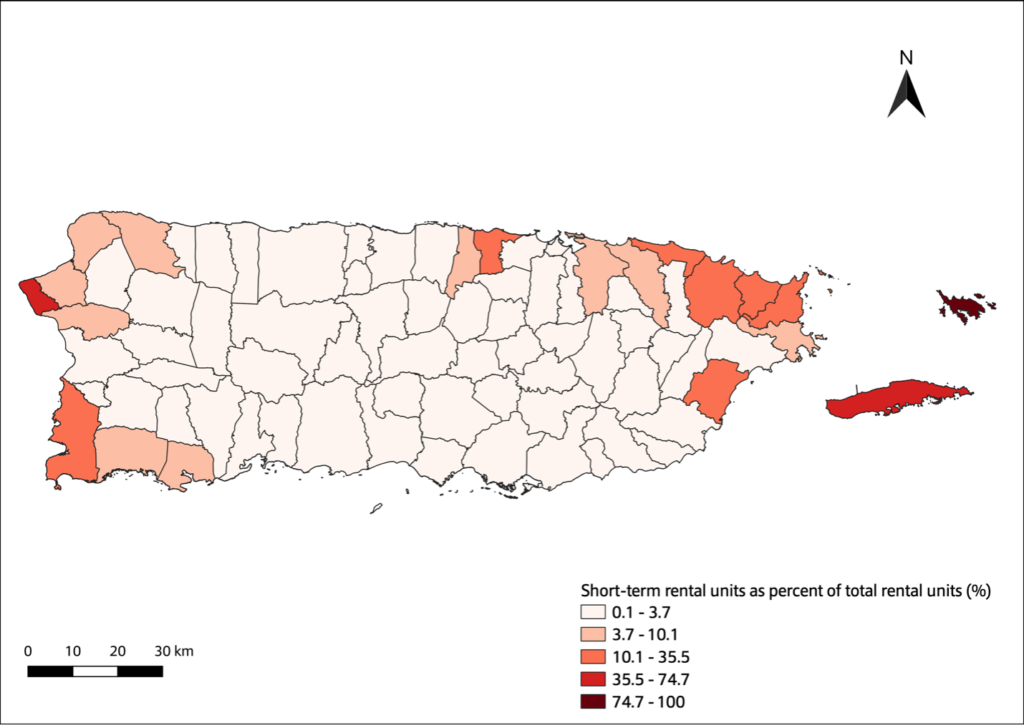

- Los ACP cubren una cantidad considerable de las unidades totales de vivienda y las unidades de alquiler a largo plazo en muchos municipios costeros.

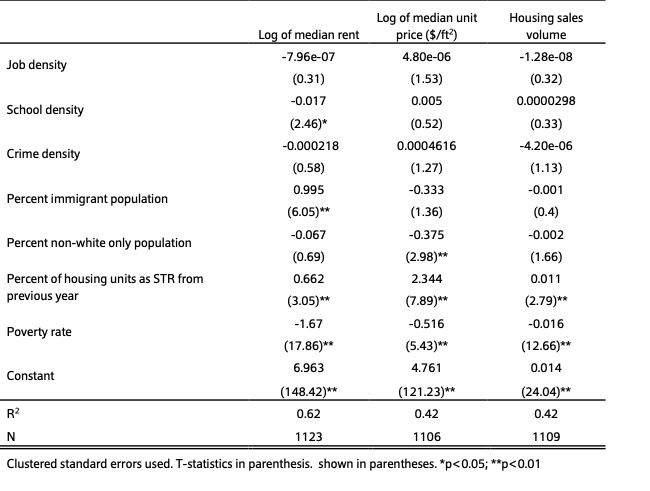

- Un incremento de 10% en la densidad de ACP (como por ciento del total de las unidades de vivienda) causa un aumento promedio de 7%, 23% y 0.1% en la mediana del alquiler, precio unitario de vivienda y volumen de venta de vivienda, respectivamente.

Nuestros hallazgos muestran que, para atender los efectos de los ACP en la asequibilidad de vivienda, Puerto Rico necesita un marco reglamentario robusto que debe ir más allá de lo que se está implantando actualmente.

Introduction

Puerto Rico faces a housing crisis marked by a shortage of affordable units, rising housing costs, increases in foreclosures and evictions, a significant and growing percentage of rent burdened households and over 300,000 dwellings damaged by storms, hurricanes and earthquakes since 2017. Amidst this dire housing scenario, there is an on-going controversy regarding the growth of short-term rentals (STRs) in Puerto Rico, which has only gotten more intense with time. STRs refer to dwellings that are rented for a time period that is typically shorter than 90 days, usually for lodging purposes, rather than residential use.

On the one hand, STRs, particularly platforms like Airbnb, have been hailed as an engine of local economic development in an island marked by a long standing fiscal and economic crisis. The argument goes that STRs allow struggling households throughout Puerto Rico to engage in entrepreneurial activity by using their underused properties for supplemental income, while fostering indirect economic benefits through tourist spending and the hiring of maintenance, construction, hosting, touring and transportation services, among many others. Previous studies on STRs in Puerto Rico have certainly made this case[1], although their claims tend to be characterized by dubious assumptions and lack of methodological transparency.

On the other hand, numerous communities and grassroots organizations across Puerto Rico have argued, often with concrete evidence, that the rapid expansion of STRs has propelled gentrification and residential displacement in their communities[2]. These residents have highlighted how individual investors, particularly those that are recipients of tax exemption decrees through Act 22 (now Act 60), have hoarded properties, evicted households, and turned housing units into STRs[3]. In other cases, communities have stressed how the growth of tourist traffic in traditional residential areas, aided by STRs, has negatively impacted their quality of life and neighborhood cohesion[4].

This report provides a detailed examination of STR activity in Puerto Rico and addresses several of the claims made by different groups through a detailed analysis focused on: hosting trends —to ascertain if the expansion of STRs is effectively providing opportunities for struggling yet enterprising households—, and the industry’s effects on housing markets and affordability —to shed light on the displacement and gentrification arguments—. We also performed a literature review on STR regulations to better understand how specific policy interventions can help address some of the impacts on housing markets.

Debates over STRs are not unique to Puerto Rico. The academic literature has documented how numerous cities across the world struggle to keep up with an industry that disrupts traditional lodging businesses, and oftentimes behaves like them, but falls outside the typical lodging regulations and legal requirements (Gurran, 2018; Gurran & Phibbs, 2017; Guttentag, 2015). Prior research has also examined the prevalence of short-term rentals, gentrification and displacement in already distressed and unaffordable cities (Wachsmuth & Weisler, 2018; Wegmann & Jiao, 2017; Yrigoy, 2018; Barron, Kung, & Proserpio, 2018; Santiago-Bartolomei, 2019). Studies have also shown how homeowners and landlords expect greater returns from short-term rentals, and thus spurred them to move away from long-term rental markets in order to attract visits from non-residents that want to reap the benefits of local amenities. With regards to hosting trends, the literature has documented increases in the commercialization or professionalization through the growing practice of hosts managing multiple STR listings (Cocola-Gant & Lopez-Gay, 2020; Cocola-Gant & Gago, 2021).

Our findings echo many of the trends evidenced in other parts of the world. Specifically, our analysis shows:

- The STR market is becoming increasingly concentrated, professionalized, and commercialized, where hosts with multiple listings accumulate a disproportionate share of properties and revenue.

- New STR listings respond to seasonal variances common with tourism in Puerto Rico, but they are also disaster-driven, given that Hurricane María and the COVID-19 pandemic caused sharp increases and drops in daily created listings.

- STRs present a substantial challenge to housing affordability, which can often lead to neighborhood gentrification:

- STRs cover a substantial amount of both total housing units and long-term rental units throughout coastal municipalities. In Culebra, properties listed on STR platforms represent almost a third of total housing units and 100% of long-term rental housing units.

- A 10% increase in STR density (as a percent of total housing units) causes an average increase of 7%, 23%, and 0.1% in median rent, housing unit prices, and housing sales volume.

Our findings show that to address STR effects on housing affordability, Puerto Rico needs a regulatory approach that goes far beyond what is currently being implemented.

STR Trends and Drivers in Puerto Rico: 2014-2020

For our analyses we used data from AirDNA, a STR market research firm located in Denver, Colorado[5]. The dataset includes all STR listings in Puerto Rico between 2014 and June 2020, as well as detailed information on daily, monthly, and aggregate STR activity and transactions.

Trends in listings

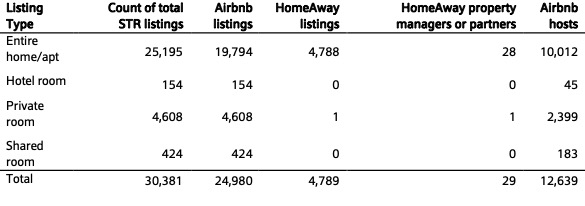

Between 2014 and 2020 (Table 1), there were more than 30,000 unique STR listings in Puerto Rico. Of these, almost 25,000 (82%) were registered under Airbnb, while some 4,800 (16%) were registered under HomeAway (now Vrbo); the remaining 2% were registered under various other platforms. Around 83% of all listings were entire homes or apartments and 15% were private rooms. Also, there were a total of 29 HomeAway managers and partners, which means that there is an average of 165 HomeAway listings managed per manager/partner, reflecting a highly concentrated host profile in Puerto Rico. Airbnb, on the other hand, had more than 12,000 hosts, for an average of 2 listings managed per host. These trends show that while Airbnb is by far the dominant STR platform in Puerto Rico, HomeAway has a much greater degree of host/property concentration, professionalization, and commercialization.

Table 1: Breakdown of STR trends in Puerto Rico between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

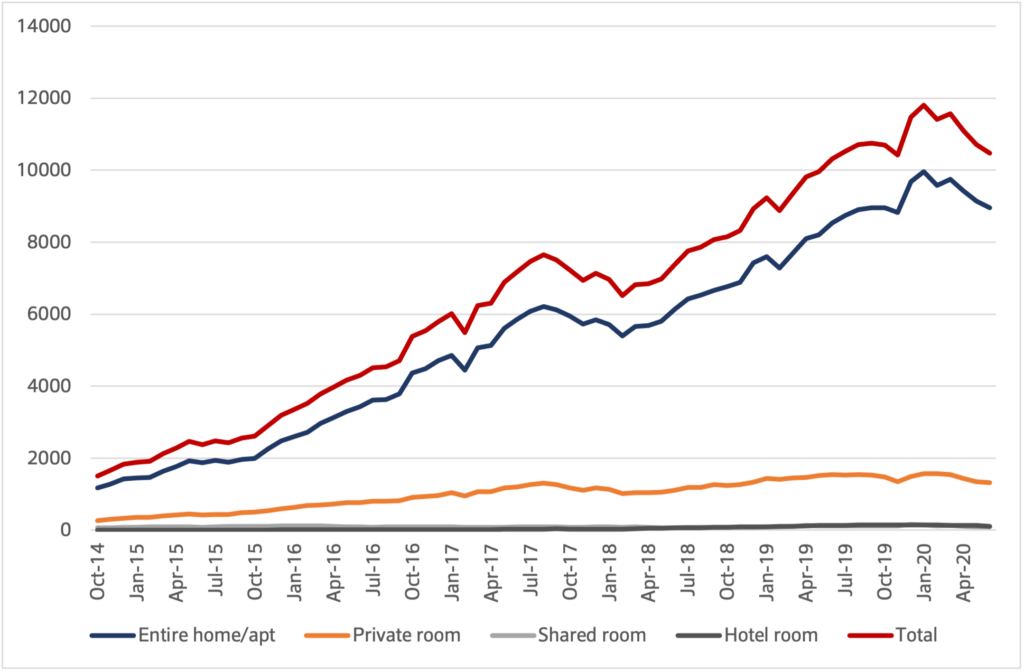

Also worth noting is that entire home/apartment listings have by far outpaced any other property type between 2014 and 2020 (Figure 1). In fact, growth in private room listings largely remained stagnant since August 2017, contrasting with commonly held views that STRs provide increasing opportunities for hosts that are looking for additional income by renting extra rooms on their properties. The large proportion of entire homes listed on STR platforms signals that there are a significant number of housing units that are outside of the traditional housing market and thus unavailable for long-term rental clients. This is particularly worrisome in Puerto Rico given rising housing costs and the limited number of units available in certain submarkets. Culebra, for example, has no public housing units and a few dozen subsidized long-term rental units, leaving the municipality’s affordable rental housing stock at the mercy of market swings.

Figure 1: Monthly STR active listings in Puerto Rico, by property type, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

Trends among hosts: Airbnb

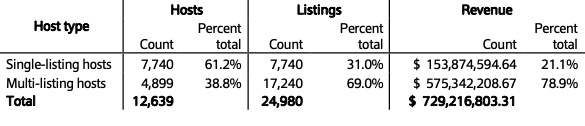

Notwithstanding HomeAway’s highly concentrated market, Airbnb hosts are certainly headed towards concentration, professionalization, and commercialization. Indeed, when breaking down the figures for accumulated listings by host and total revenue between 2014 and 2020, there are important differences between single and multi-listing host (Table 2). Data show that single-listing hosts (SLH) and multi-listing hosts (MLH), those with 2 or more properties listed, represent 61% and 39% of total Airbnb hosts, respectively. However, when it comes to share of property listings, MLHs cover 69% of total listings in Puerto Rico. Furthermore, of the more than $700 million accumulated through STRs between 2014 and 2020, 79% of total revenue have gone to MLHs.

Table 2: Breakdown of Airbnb host profile between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

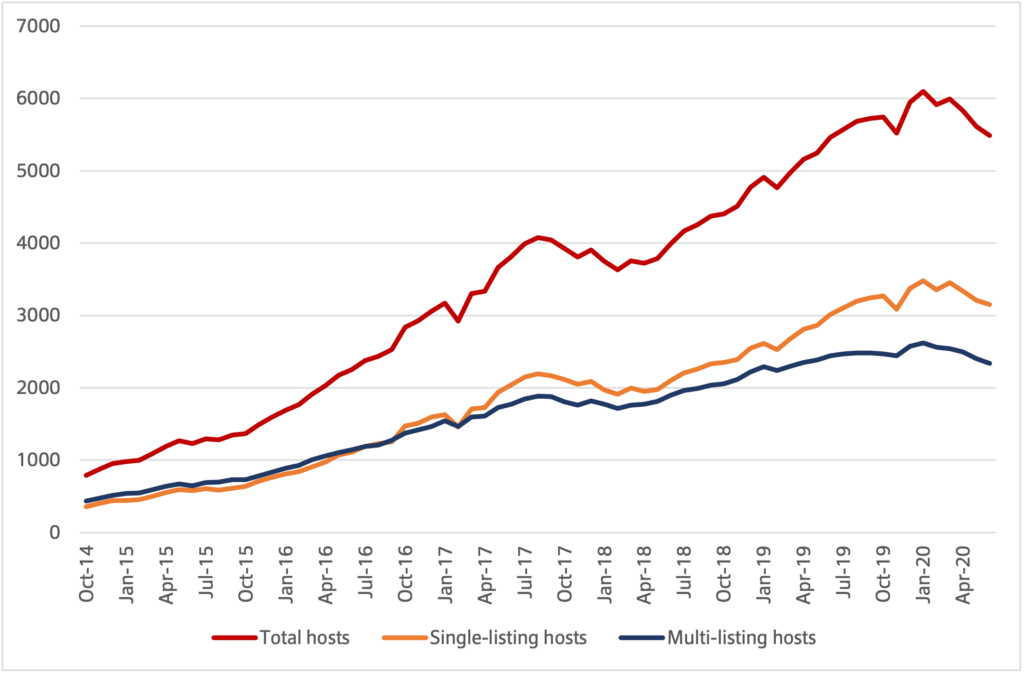

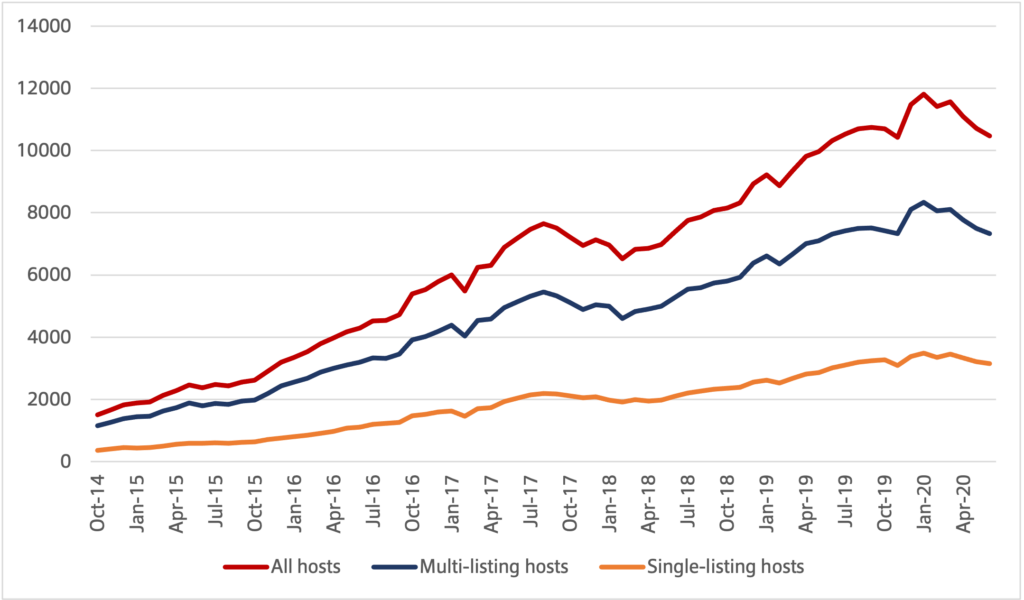

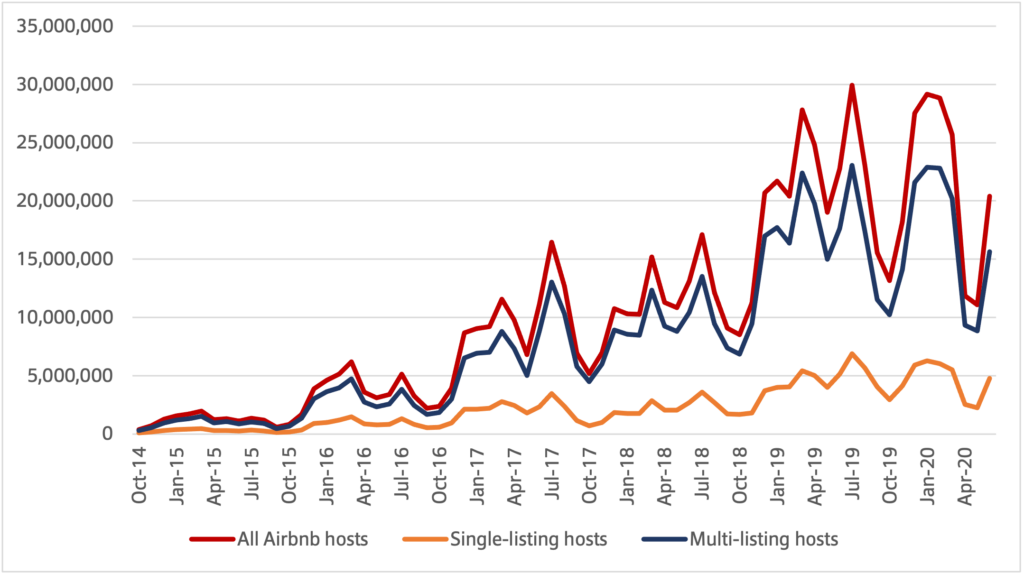

Looking at monthly active listings in the Airbnb platform shows that the aforementioned divergence between MLHs and SLHs has been growing throughout the 2014 to 2020 period. Although the number of monthly active MLHs and SLHs seem to have been more or less equal between 2014 and 2016 (with MLHs outnumbering SLHs in many instances), SLHs have been outnumbering MLHs in the same approximately 60%:40% ratio since then (Figure 2). Nevertheless, when examining active monthly listings, MLHs have consistently captured 70% of total listings between 2014 and 2020 (Figure 3). With regards to total monthly revenue among active hosts, MLHs have steadily accrued between 75% to 80% of total monthly revenue between 2014 and 2020 (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Monthly number of active Airbnb hosts, by host type, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

Figure 3: Monthly number of active Airbnb listings, by host type, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

Figure 4: Monthly revenue from Airbnb listings, by host type, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA.

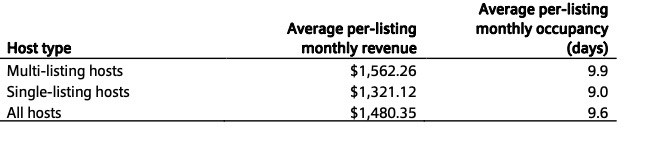

A closer look at the property level data reveals some interesting trends regarding revenues and occupancy that signal a convergence in commercial and management behavior between MLHs and SLHs since Hurricane María made landfall on September 20th, 2017. As Table 3 demonstrates, MLHs achieved a greater average per-listing monthly revenue and occupancy than SLHs, but the differences are not too stark. These figures demonstrate that the differences at the property level between MLHs and SLHs do not explain the glaring unequal outcomes in terms of revenue accumulation. Simply put, the divergence is most probably due to property hoarding by MLHs.

Table 3: Per-listing profile of Airbnb hosts, by host type, between September 20th 2017 and June 30th 2020. Source: AirDNA.

Drivers of STR activity in Puerto Rico

Beyond identifying some tendencies within the data, it is important to examine what are some of the possible drivers behind the observed trends. To carry out this type of analysis, we examined data on new, unique STR listings created daily through the Airbnb platform.

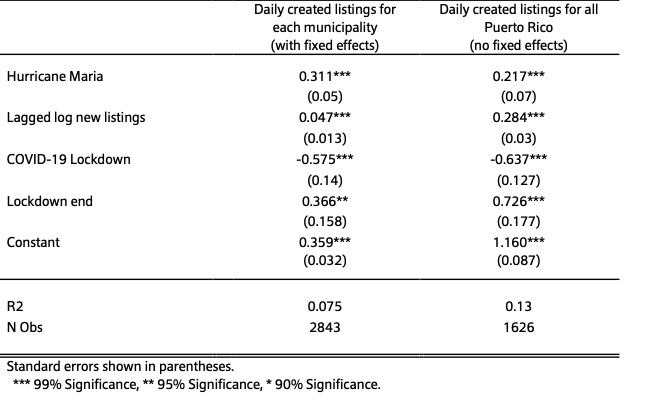

We constructed two panel regression models using daily new Airbnb listings between 2014 and 2020 as the dependent variable for both models. They also include control dummy variables for those listings created before or after Hurricane María, the COVID-19 lockdown[6], and the end of the lockdown[7]. We also included a lagged control variable of new listings at the previous day to account for “inertia” in STR listing creation. The first model focuses on daily created listings at the municipal level and includes dummy variables for the municipality and month of creation to control for location and time fixed effects. The second model focuses on daily created listings for all of Puerto Rico.

The findings (Table 4) show that Hurricane María increased average daily created Airbnb listings between 22% and 31%. The COVID-19 lockdown decreased daily created listings between 58% and 64%, while the end of the lockdown increased daily created listings between 37% and 73%. The first model showed that created listings respond to seasonal variations, but both models clearly convey that the expansion and contraction of Airbnb STR listings, in recent years, are significantly driven by disaster activity.

Table 4: Regression results for possible drivers of daily created Airbnb listings.

Impact of STRs on Housing in Puerto Rico

STRs and the Housing Stock

As previous studies have shown, a key pathway through which STRs affect housing affordability is by reducing the housing supply for both long-term rentals and housing sales (Wachsmuth & Weisler, 2018; Wegmann & Jiao, 2017; Yrigoy, 2018; Barron, Kung, & Proserpio, 2018; Santiago-Bartolomei, 2019). Therefore, the number of STR listings[8] as a percentage of housing units becomes a key benchmark measure of how these rentals affect housing supply. In the case of Puerto Rico—during the study period—coastal municipalities were much more prone to having a higher rate of STR coverage of housing units, with the highest rates being registered in the northeastern coastal range. In Vieques, almost 15% of housing units were listed at some point in an STR platform, while this figure reaches almost 30% in Culebra (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: STR listings as a percent of total housing units per municipality, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA and the US Census Bureau (PRCS).

When looking at STR listings as a percentage of rental housing units for the same period[9], the impact on housing availability can be discerned more clearly (see Figure 6). For San Juan, Carolina, Fajardo, Guánica, Lajas, and Fajardo, registered STRs cover between 3.7% to 10.1% of long-term rental units. In Dorado, Loíza, Luquillo, Río Grande, Fajardo, Humacao, and Cabo Rojo this figure reaches between 10.1% and 35.5%. In Rincón, registered STRs cover 35.5% of long-term housing rental units, while in Vieques this number reaches 74.7%. In Culebra registered STRs cover 100% of long-term rental units. This does not necessarily mean that Culebra has no long-term rental units available, but rather that the number of STR units equals or surpasses those for long-term rent.

Figure 6: STR listings as percent of total long-term rental housing units per municipality, between 2014 and 2020. Source: AirDNA and US Census Bureau (PRCS).

STR effects on Housing Markets

Given that housing markets respond to labor markets and agglomeration economies, we focused our statistical analysis on the regional level. We selected the San Juan Metropolitan Area (SJMA), a fifteen-municipality region that follows the Puerto Rico Planning Board’s functional area delimitation for the Puerto Rico Land Use Plan (Figure 5). Our analysis comprises the time period between 2017 and 2019. We chose 2017 as a starting point to focus on the immediate time periods before and after Hurricanes Irma and María. We excluded observations from 2020 because our AirDNA dataset includes STR information for up to June 2020, but also because the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted housing markets in ways that are yet to be made clear for modeling purposes.

Figure 7: Location and delimitation of the San Juan Metropolitan Area. Source: Puerto Rico Planning Board.

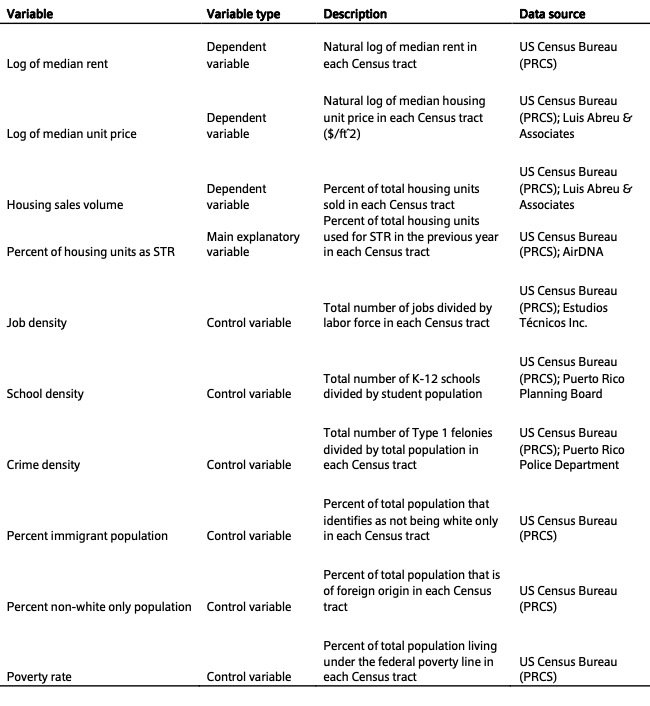

We developed a panel dataset where Census tracts in the SJMA, between 2017 and 2019, were the unit of analysis and performed a pooled ordinary least squares regression to examine how STRs affect housing markets in diverse ways. Specifically, we included median rent, median unit price and housing sales volume as the dependent variables and percent of housing units used for STR as the main explanatory variable (see Table 5). We also included controls for number of jobs, school access, crime rate, racial composition, immigrant presence and poverty rate for each tract and each year as control variables. The model also includes municipal and yearly fixed effects, while standard errors were clustered at the tract level.

Table 5: Regression analysis variable list.

Regression results show that, consistent with research conducted around the world, STRs affect housing markets in various ways (Table 6). A 10% increase in the share of STR of total housing units in a given Census tract results in an average increase of 7% in the median rent, 23% in median housing unit price, and 0.1% in housing sales volume in the following year. These estimates are statistically significant, even after controlling for: local amenities and disadvantages, poverty, racial composition, and fixed effects.

Table 6: Regression results for STR effect on housing markets.

Regulatory Landscape for STRs

Regulatory policy regarding STRs is relatively nascent but highly diverse in its approach as well. Cities throughout the US, Europe, and Asia have identified STRs as a significant disruptor of housing markets that has affected access to affordable housing, but their policy responses demonstrate a high propensity for experimentation, given the relative newness of the issue. To identify trends within the regulatory landscape, we performed a thorough literature review and summarized some of the measures taken in different parts of the world. The exercise examined policies that have either been implemented or are proposed as potential regulatory policies.

It should be noted that, in spite of approved (i.e. Dorado) and proposed ordinances to regulate STRs at the municipal level (e.g. San Juan), the only existing regulation regarding STRs in Puerto Rico is the Tourism Company’s requirement that STR property owners pay a local “room tax” and its ensuing regulations aiming at host registry and property health and safety. Per Puerto Rico’s Act 272 of 2003, as amended, any property owner that rents their property on a short-term basis—defined as a period of less than 90 consecutive days—must charge a 7% room occupancy tax and remit it to the Puerto Rico Tourism Company. This specific regulation is geared towards addressing any perceived disadvantages caused to traditional lodging services (e.g., hotels and hostels) by STRs, but it is wholly unrelated to the potential impacts to local housing markets. This is a very timid and limited rule when compared to those implemented in other cities across the world, which aim to explicitly address their concerns regarding potential impacts to housing markets by STRs.

Below is a summary of the main regulatory approaches that have been implemented throughout the world. In most cases, local jurisdictions combine two or more of these approaches—instead of a total ban of STRs, which some have adopted—:

- Licensing and registration system: The implementation of a licensing and registration system for property owners, hosts, and/or guests of STR properties.

- Regulating location of STRs: The implementation of policies and regulations to limit STRs to certain designated areas within cities.

- Regulating the number of STRs: The implementation of policies and regulations to cap the number of STRs within cities.

- Restricting number of guests: The implementation of policies and regulations to cap the number of guests allowed to stay in STRs within cities.

- Regulating accommodation type: The implementation of policies and regulations to limit STRs to certain accommodation or dwelling types, such as limiting STRs to private or shared rooms within housing units.

- Restricting number of days/nights: The implementation of policies and regulations to limit the number of days in a month or year that a housing unit can be used for STR.

- Requiring rented rooms to be in owner occupied homes: The implementation of policies and regulations to limit STRs to owner-occupied housing units.

- City monitoring and the creation of a database: The development of monitoring tools, such as newly created databases and other information technologies (IT), to ensure compliance with existing STR regulations and inform enforcement efforts.

- Punishment for compliance failures: The implementation of punitive measures to instances of regulatory non-compliance regarding STRs.

- Health and safety: The implementation of policies and regulations to ensure the health and safety of STR guests and nearby residents, such as requiring insurance or certain facilities to avoid hazards.

- Tax collection for STRs: The implementation of tax policies and regulations to STR hosts and/or STR property owners.

Notable among the findings stemming from the review is the breadth of regulations implemented by cities throughout the US, Europe, and Asia, but also how little research has been conducted to ascertain their effectiveness. Cities have been experimenting widely, with little to no indication if many of these regulations are effective in curbing the negative effects of STRs on housing markets. However, places that have achieved some degree of success of reducing the effect of STRs on housing affordability, albeit with very limited and minor mitigating effects, have some common characteristics: (1) they tend to establish a registering and licensing system for STR hosts or property owners; (2) they have developed digital monitoring tools to ensure compliance; (3) they tend to place restrictions on locations and caps on number of days per year that STRs can operate; (4) they tax STRs for occupancy; (5) and they tend to fine STR hosts and property owners in cases of noncompliance. Examples include: New Orleans, Santa Monica, Los Angeles, Denver, Barcelona, Berlin, Tokyo, and Taiwan, among others. These trends do not prove that other approaches are ineffective, but that detailed analyses on regulatory effectiveness are seriously lacking. In addition, given the lack of transparency and unwillingness from many of the STR platforms to share their data, almost all of the examples studied highlighted the difficulty of having access to reliable data and setting up digital monitoring tools, primarily because they are heavily dependent on IT capabilities that are likely beyond many, if not most, city governments.

Appendix 1 provides a detailed summary of the literature review on STR regulation. The information was extracted and summarized during September-October 2022. It includes information on the type of regulation, the city or country where the regulation has been implemented to address negative externalities from STRs (primarily Airbnb), implementation details, positive and negative impacts, possible barriers for implementation, references consulted and additional information found. For those articles that specified types of regulations that have been implemented, but have limited information on impacts/results and possible barriers, a note has been added that indicates “Does not specify. Further research is needed.”

Conclusion

Contrary to the popular narratives surrounding STRs, particularly the idea that these digital platforms mainly provide economic development opportunities for small property owners who’d like to generate a new source of additional income by subletting their underused units, this housing market segment is becoming increasingly concentrated, professionalized, and commercialized in Puerto Rico. SLHs have increasingly outnumbered MLHs since 2016, but it is the latter group who have accumulated more than two thirds of listings and almost 80% of accumulated revenue. As the data clearly demonstrates, the STR market has tilted heavily towards professional or commercial hosts with multiple listings under their name.

Also, while new STR listings respond to seasonal variances common with tourist activity in Puerto Rico, they are also highly susceptible to disasters. In the aftermath of Hurricane María, for example, new STR listings (measured daily) rose by around 30%. This finding demonstrates that disasters create the ideal conditions for investors who take advantage of short-term drops in housing prices to buy properties for STR conversion, as well as an increase in single-listing hosts that are looking for additional income during difficult times.

With regards to how STRs affect Puerto Rico’s housing sector, we found that these rentals cover a substantial amount of both total housing units and long-term rental units throughout coastal municipalities. In the island municipality of Culebra, between 2014 and 2020, the sum of STRs registered in a platform during that period were almost a third and 100% of total housing units and rental housing units, respectively. Also, when examining local effects, the expansion and concentration of STRs in neighborhoods within the San Juan metropolitan area (as a percent of total housing units) are associated with average increases in median rent, housing unit prices, and housing sales volume.

Given the trends towards market concentration and professionalization, as well as its documented impacts on housing affordability, it is clear that STR expansion and concentration has led to the gentrification of numerous neighborhoods in Puerto Rico. This evidence underscores the need for a robust regulatory framework that significantly improves and strengthens the very lax governmental measures implemented in Puerto Rico. Our review of regulatory approaches in cities that achieved limited success in curtailing the negative effects of STRs reveals that Puerto Rico must quickly develop the capacity to implement an IT infrastructure that enables monitoring, reliable property inventories, and a licensing and/or registration system for STR hosts and/or property owners (ideally, it should devise a registering system for all landlords and property owners). Puerto Rico should also consider limiting STR activity to a few areas and heavily restricting the number of days per year where these activities should take place, particularly in urban and/or coastal areas. Implementing such a framework will require action and investments at both the central and municipal government levels. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done given the existing austerity regime that has been in place for well over a decade and a half, which has severely hindered institutional capacity throughout municipalities and central government agencies. Nonetheless, concrete actions must be taken in order to mitigate the negative impacts of STRs in an already tight housing market that fails to provide opportunities for low- and moderate-income households.

Regardless of the regulatory approach to be implemented, it is important to note that much more needs to be done to address the shortcomings of Puerto Rico’s housing sector. A comprehensive housing planning and policy framework that helps expand access to affordable housing and reduce the likelihood of displacement is urgently needed. Puerto Rico’s longstanding housing crisis requires a combination of adequate policy tools and programs. Addressing the negative impacts of STRs would be an important step in the right direction.

References

Barron, K., Kung, E., & Proserpio, D. (2018). The Sharing Economy and Housing Affordability: Evidence from Airbnb. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3006832

Chang, H.H. (2020). Does the room sharing business model disrupt housing markets? Empirical evidence of Airbnb in Taiwan. Journal of Housing Economics, 49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2020.101706

Cheng, M., & Foley, C. (2018). The sharing economy and digital discrimination: The case of Airbnb. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70, 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.002

Cocola-Gant, A., & Gago, A. (2021). Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(7), 1671-1688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19869012

Cocola-Gant, A., & Lopez-Gay, A. (2020). Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’ enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Studies, 57(15), 3025-3043. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020916111

Edelman, B. G., & Luca, M. (2014). Digital discrimination: The case of Airbnb. Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working Paper, (14–054). https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2377353

Edelman, B., Luca, M., & Svirsky, D. (2017). Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160213

Gurran, N. (2018). Global Home-Sharing, Local Communities and the Airbnb Debate: A Planning Research Agenda. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(2), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1383731

Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2017). When Tourists Move In: How Should Urban Planners Respond to Airbnb? Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1249011

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Nieuwland, S. & van Melik, R. (2020). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(7), 811-825. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1504899

Santiago-Bartolomei, R. (2019). Property and Labor Formalization in the Age of the Sharing Economy: Airbnb, Housing Affordability, and Entrepreneurship in Havana. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/pagepdf/2385257995?accountid=44825

van Holm, E.J. (2020). Evaluating the impact of short-term rental regulations on Airbnb in New Orleans. Cities. 104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102803

von Briel, D. & Dolnicar, S. (2020). The evolution of Airbnb regulation – An international longitudinal investigation 2008-2020. Annals of Tourism Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102983

Wachsmuth, D., & Weisler, A. (2018). Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(6), 1147–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18778038

Wegman, J. & Jiao, J. (2017). Taming Airbnb: Toward guiding principles for local regulation of urban vacation rentals based on empirical results from five US cities. Land Use Policy, 69, p. 494-501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.025

Yrigoy, I. (2018). Rent gap reloaded: Airbnb and the shift from residential to touristic rental housing in the Palma Old Quarter in Mallorca, Spain. Urban Studies, 004209801880326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018803261

Endnotes

[1] See Oxford Economics study on STRs in Puerto Rico: https://sincomillas.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Airbnb-PUERTO-RICO-SPANISH-V6-small.pdf

[2] See situation in Puerta de Tierra, San Juan: https://www.wapa.tv/noticias/entretenimiento/inversionistas-compran-edificios-en-puerta-de-tierra-para-botar-a-residentes–denuncia-colectivo_20131122531752.html

[3] See investor activity in Puerta de Tierra: https://www.metro.pr/noticias/2022/03/22/denuncian-que-beneficiarios-de-la-ley-22-estan-acaparando-propiedades-en-puerta-de-tierra/

[4] See situation in the Dos Pinos suburb in San Juan: https://www.elnuevodia.com/negocios/turismo/notas/relatan-una-agonia-con-alquileres-de-corto-plazo-en-comunidad-de-rio-piedras/

[5] Funding to purchase the AirDNA data was provided by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

[6] The COVID-19 lockdown in Puerto Rico was put into effect on March 15th 2020: https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/locales/notas/wanda-vazquez-decreta-toque-de-queda-para-todo-puerto-rico-para-contener-el-coronavirus/

[7] The 24 hour lockdown ended on June 16th 2020: https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/locales/notas/wanda-vazquez-anuncia-que-el-toque-de-queda-ahora-comenzara-a-las-1000-pm/

[8] This figure includes all properties that have been registered in an STR platform, regardless of whether they registered bookings or not, since these units could presumably become unavailable for long-term residential use.

[9] This measure does not imply that specific long-term rental units are being used as STR units. Rather, it is an indirect measure of potential supply constraints in long-term rental units because of STR units.