Published on March 14, 2024 / Leer en español

In This Issue

CNE’s Policy Director analyzed the recently published summary of the Puerto Rico Grid Resilience and Transitions to 100% Renewable Energy Study (“PR100” or the “Study”). Click here to read the full analysis.

While the PR100 Final Report will not be released until late March, in this issue of the CNE Review we highlight some of the findings of the summary due to their importance and their potential policy implications for Puerto Rico’s electricity sector.

In the full analysis, we outline the U.S. Department of Energy’s (“DOE”) scenarios, based on different assumptions, that would enable Puerto Rico to achieve the goal of 100% renewable generation by 2050. While this study provides valuable guidance, difficult decisions will have to be made by Puerto Rico’s government that imply important tradeoffs between affordability, time, and resources.

CNE advocated strongly for Act 17 of 2019 and we believe in the goals set by this law. Puerto Rico needs an electricity system based on renewable energy that is both reliable and affordable. But as the country moves toward this transition, we need to make sure that we don’t lose sight of the well-being of both families and businesses. Our next steps will include analyzing the DOE’s full report which will be made public at the end of March. CNE will continue to monitor, analyze, make recommendations, and advocate for an affordable and sustainable electricity system for Puerto Rico.

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Analysis of the PR100 Summary Report

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

Introduction

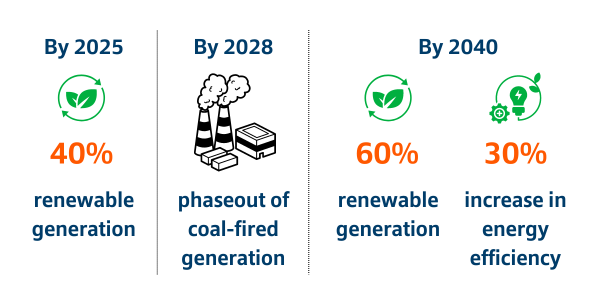

The Puerto Rico Energy Public Policy Act of 2019 (“Act 17 of 2019”) requires that Puerto Rico meet 100% of its electricity needs with renewable energy by 2050. To reach that objective, Act 17 set the following interim goals:

On February 7, representatives of the DOE, including Secretary Granholm, presented a summary of the findings of the PR100 Study. This Study was the product of a two-year effort led by the DOE, with the collaboration of the University of Puerto Rico Mayaguez and other local stakeholders, to analyze and identify possible pathways for Puerto Rico to achieve its goal of generating 100% of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2050.

While public discussion has focused on a few of the Study’s main findings indicating that Act 17’s requirement can be met by 2050, we want to highlight the different scenarios presented in the summary, the tradeoffs required, and their potential policy implications.

In this process, it is also crucial for local decision-makers to take into consideration the following unanswered questions and inform all stakeholders on how they will be addressed:

- How much will it cost to achieve maximum resilience in Puerto Rico?

- How much can consumers afford or are willing to pay to transition to renewables?

- Which agency or entity will decide on the scenario, if any, to be implemented in Puerto Rico?

- What is the economic impact of each scenario, with their variants, on GNP, GNP growth, consumption, employment, and income?

- If the cost of maximizing resilience is too high, who decides which geographic areas will be excluded?

- What is the total investment required by system segment (transmission, distribution, generation, battery storage, access, and connectivity infrastructure) to achieve the 100% renewable energy objective? How will that investment be financed (again broken down by segment)?

- How much funding has been identified, committed, and spent for each of the segments?

Scenarios, Tradeoffs & Policy Implications

Scenarios

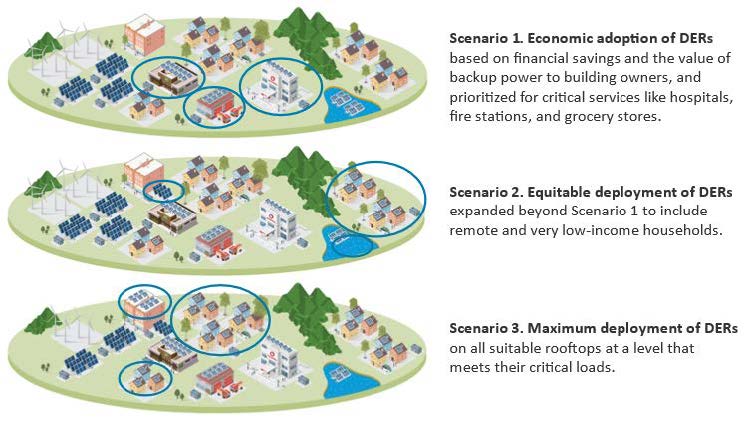

The DOE, together with several of the national labs and local stakeholders, modeled three scenarios to meet the 100% target by 2050. Each scenario assumes the current dilapidated electric grid is sufficiently repaired to support the reliable operation of the electric system before the full deployment of renewable generation. Then the scenarios are initially differentiated by varying the adoption level of distributed energy resources (“DERs”) such as rooftop solar, utility-scale solar photovoltaics (“PVs”), and wind generation units, among others. Two variations are added for land use (how much land is needed to develop these new projects), and electric load with 2 variants each, resulting in a total of 12 scenario variations.

Source: PR100 Summary, p. 8.

Scenario 1 assumes the adoption of DERs is driven primarily by “economic factors and is based on financial savings and the value of backup power to building owners”. It also prioritizes the deployment of DERs on “critical infrastructure such as hospitals, fire stations, and grocery stores”. This is called the “Economic” Scenario.

Scenario 2 extends the adoption of DER beyond the levels specified in Scenario 1 to include “very low-income households (0%-30% of area median income) and those in remote areas who would not have bought systems solely based on economics”. This is called the “Equitable” Scenario.

Scenario 3 models the “maximum deployment of DERs on all suitable rooftops at a level that meets their critical loads” (PR100 Summary, p. 8). This is called the “Maximum” Scenario.

Regardless of the scenario, the DOE states, increased system capacity is needed immediately to maintain its stability.

Tradeoffs

We found that the Scenarios modeled by the DOE present significant tradeoffs between resilience (Scenarios 2 and 3) and energy affordability (Scenario 1); between land use and energy affordability (“less land” scenarios tend to be more expensive); between meeting the 40% goal by 2025 and achieving acceptable grid reliability in the short term; and between incurring high short-term costs to obtain long-term benefits, depending on the scenario to be implemented.

The existence of these tradeoffs raises the question of which agency or entity should be in charge of making these decisions. We strongly recommend that the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (“PREB”) be in charge of making these decisions.

Policy Implications

To Achieve the 2025 Interim Goal:

By mid-2023, notwithstanding a significant increase in distributed solar PV generation, only between 3% and 5% of the generation capacity available for the grid came from renewable sources.

This means that Puerto Rico is significantly behind schedule to meet the interim target of 40% renewable generation by 2025. Puerto Rico will likely miss it.

Furthermore, according to the DOE, the all-in average retail rate would increase between 66% and 83% between 2020 and 2025, depending on which scenario is implemented.

A rate increase of this magnitude would have severe, material adverse effects on the economy of Puerto Rico in the short term and is simply not economically feasible. It will be necessary to mitigate these negative effects, either through subsidies, an extension of the timeline for achieving the transition, or through other policies.

Achieving the 2050 Goal

According to the Study, it is feasible to achieve the objective of 100% renewable energy generation in Puerto Rico by 2050 without using agricultural lands for developing utility-scale generation. However, the economic cost of the transition to 100% renewable energy by 2050 is quite significant, regardless of the scenario.

In addition, there appears to be a contradiction in the Study since it states that the 100% objective can be met using “mature” technologies such as utility-scale PV, distributed PV, and land-based wind. Yet, later on in the report, it states that the optimal resource mix to meet the 100% objective includes generation from engines using biodiesel fuel. To our knowledge such technology is not yet mature or commercially viable for the generation of electric power.

The PR100 Study forecasts loads out to 2050 and models capacity expansion to find the lowest-cost system for each scenario while meeting load requirements. In general, the scenarios outlined in the report with higher deployment of DERs using less land tend to be, on average, more expensive than other scenarios. They also result in higher rates for the consumer and induce greater short-term adverse effects on the Puerto Rican economy. How will these adverse effects be minimized if one of these scenarios is chosen?

The Challenge of Forecasting Demand

Forecasting long-term energy demand trends is one of the most complex issues in this planning exercise. The time horizon is too long, there are too many variables as well as multiple unknown unknowns (for example, the risk of a major hurricane striking the island ten years from now). Therefore, no one knows what the demand for electricity will be in Puerto Rico twenty-five years from now. It is still necessary, however, to take into account potential risks and uncertainties and start the transition to achieve the 100% goal by 2050. This issue is also important in the court-led process to restructure the debt of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (“PREPA”) that is currently ongoing in federal court.

Given this significant uncertainty, we recommend that representatives of the DOE, the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board, Genera, LUMA, PREPA, and the PREB meet and seek agreement on a single set of forecasts out to 2050 and that the same projections be used for both the development of PREPA’s new IRP and in PREPA’s financial Plan of Adjustment that will be eventually certified by the federal court. Using one set of load forecasts for operational planning purposes (the IRP) and another for financial planning purposes (the Plan of Adjustment) does not make sense.

More Information is Needed

The PR100 Summary appears to present a good preview of the findings of the PR100 Study. From the Summary it seems that the PR100 Study is a thorough and thoughtful analysis carried out by a respected group of stakeholders. It is a welcome contribution to the public debate and a valuable resource for those who analyze and study Puerto Rico’s electricity system. We hope that the final report provides more details on the following critical areas:

- Load Forecasts: We need more information about the methodology used by the DOE to forecast electricity demand over the long term to reach any conclusion regarding the reasonableness of its estimates. Specifically, we need to know whether the DOE estimated demand functions for commercial, industrial, and residential users; the price elasticities used and how they were calculated; and additional information regarding their energy efficiency estimates.

- Biodiesel Fuels: We are not familiar with this technology and need more information before reaching any conclusions regarding the feasibility of its future use in Puerto Rico for the generation of electric power.

- Economic Impact Analysis: We need more information regarding the economic impact of rate increases in the short term on GNP level, GNP growth, employment, income, and consumption expenditures to assess the economic feasibility of the different scenarios.

- Total Capital Expenditures and Sources of Financing: It would be useful if the final PR100 Study included a breakdown, by scenario and system segment (transmission, distribution, generation, energy storage, access infrastructure, etc.), of (1) all the capital expenditures required to achieve the 100% goal by 2050 and (2) potential financing sources for each of these expenditures.

On Our Radar…

![]() Reconstruction Spending – A recent report from the United States Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) found that “the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had awarded about $23.4 billion in Public Assistance to Puerto Rico’s permanent recovery work related to hurricanes Irma and Maria and the 2019 and 2020 earthquakes, as of June 2023. Of that, Puerto Rico has expended about $1.8 billion and a substantial amount of permanent work remains. Further, about $11.3 billion of the awarded funds needs FEMA’s authorization before Puerto Rico can expend it.” In other words, we have made some progress but a lot of work remains to be done.

Reconstruction Spending – A recent report from the United States Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) found that “the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had awarded about $23.4 billion in Public Assistance to Puerto Rico’s permanent recovery work related to hurricanes Irma and Maria and the 2019 and 2020 earthquakes, as of June 2023. Of that, Puerto Rico has expended about $1.8 billion and a substantial amount of permanent work remains. Further, about $11.3 billion of the awarded funds needs FEMA’s authorization before Puerto Rico can expend it.” In other words, we have made some progress but a lot of work remains to be done.