Published on May 8, 2020 / Leer en español

Four things you should know today

1) Providing pandemic rental assistance in Puerto Rico

Analysis by Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, PhD, Research Associate at CNE, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves, PhD, Research Director at CNE

It is the beginning of May, and as tenants in Puerto Rico are well aware, rents are due around this time. After almost two months of lockdown measures to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many low-income renters find themselves in a difficult position to make payments on time. In the recent past, CNE has argued that a rent moratorium is needed, one that includes both a freeze on evictions (which has de facto come into effect through the suspension of these court orders in Puerto Rico) and a subsidy or direct assistance to renters, a measure also supported by advocates in the island. This latter proposal is important, since a total freeze on rent payments may leave landlords in a tight financial bind, rendering them unable to pay mortgages and other financial obligations.

How a rent assistance program is ultimately implemented is important, since an overly bureaucratic structure, or a program created “from scratch” might end up failing to reach renters expediently—the erratic and slow disbursement of the CARES Act stimulus checks in Puerto Rico is a good example. Given these difficulties, there is consensus among housing experts and advocates that the best way to implement a pandemic rent assistance program in the middle of an emergency is by expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program. This program, commonly referred to as Section 8 vouchers, is a housing rental subsidy administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). It provides vouchers to low-income households (defined as households with incomes lower than 50% of area median income, or AMI) to subsidize rents in the open market, with households paying up to 30% of their monthly income and the government paying the rest.

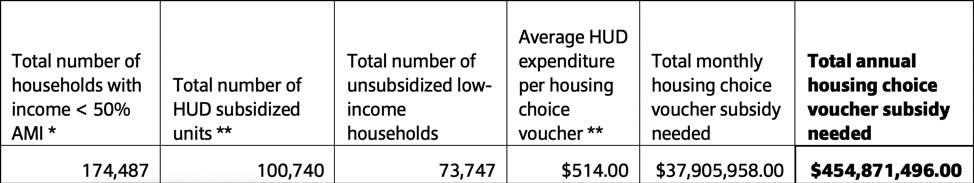

We carried out a rough calculation that yielded a conservative estimate of how much would be needed to expand the Housing Choice Voucher program, in order to provide pandemic rental assistance in Puerto Rico that meets the needs of its low-income renters. These were our findings:

Puerto Rico would need at least an additional $455 million to provide rental assistance for one year, in order to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on low-income renters.

* Source: 2018 5-year average PRCS and HUD income limits for 2020

** Source: HUD data on assisted housing

How did we arrive at this figure? Using data from the 2018 Puerto Rico Community Survey and HUD’s income limits for each municipality, we estimated the total number of low-income households that have incomes lower than 50% of AMI. We then used HUD data on assisted housing to determine the total number of housing units that receive rent subsidies from HUD, including Housing Choice vouchers, project-based Section 8, public housing, and Section 202, among others. We subtracted this number from the total number of households with incomes under 50% of AMI in Puerto Rico, to determine the total number of households who are not currently served by HUD’s rental assistance programs.

HUD data on assisted housing showed that the average per unit subsidy through the Housing Choice Vouchers program was $514 per month, in 2019. Multiplying this number by the total number of unsubsidized low-income households, yielded a monthly rental assistance gap of approximately $37.9 million, or $455 million for one year.

This analysis is part of a series of policy advocacy efforts performed by CNE’s Blueprint Initiative, in partnership with Habitat for Humanity Puerto Rico.

2) Release of detailed CDC guidance for reopening put on hold

The Trump administration has stopped the publication of a report drafted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) team, entitled “Guidance for Implementing the Opening Up America Again Framework,”. According to the AP, “the guidance contained detailed advice for making site-specific decisions related to reopening schools, restaurants, summer camps, churches, day care centers and other institutions. It had been widely shared within the CDC and included detailed “decision trees,” flow charts to be used by local officials to think through different scenarios.”

In contrast, “the White House’s own “Opening Up America Again” guidelines released last month were more vague than the CDC’s unpublished report. They instructed state and local governments to reopen in accordance with federal and local “regulations and guidance” and to monitor employees for symptoms of COVID-19.”

However, state and local officials keep contacting the CDC for science-based advice about lifting lockdown restrictions and CDC scientists continue to respond to these requests “behind the scenes.” It is a sad situation, though, when some of the world’s top public health experts are forced to work undercover, fearing retaliation from the White House.

3) Congress stalls as food insecurity increases

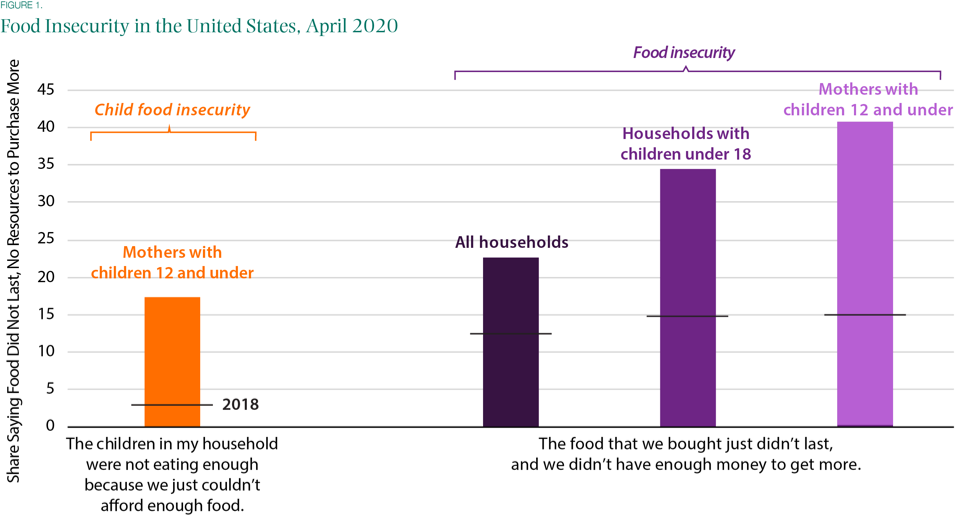

A new study by Lauren Bauer, a Fellow at the prestigious Brookings Institution, found that close to 20 percent of households with children 12 years old or younger were “not eating enough because they could not afford enough food.” Furthermore, as shown in the chart below “by the end of April, more than one in five households in the United States, and two in five households with mothers with children 12 and under, were food insecure.”

Yet, as the New York Times reports, “Republicans have balked at a long-term expansion of food stamps — a core feature of the safety net that once enjoyed broad support but is now a source of a highly partisan divide” while “Democrats want to raise food stamp benefits by 15 percent for the duration of the economic crisis, arguing that a similar move during the Great Recession reduced hunger and helped the economy.”

According to the Times, “during the Great Recession, Congress increased maximum benefits by about 14 percent and let states suspend work rules. Caseloads soared. By the time the rolls peaked in 2013, nearly 20 million people had joined the program, an increase of nearly 70 percent, and one in seven Americans received food stamps, including millions with no other income.”

Yet, as cars line up for miles at food banks across the nation, Congress continues to engage in petty partisan skirmishes. Which is highly ironic, given that the food stamp program in its current form was a compromise between the liberal George McGovern and the conservative Bob Dole.

4) Financial markets have become untethered from the real economy

Economic news have been quite gloomy recently. Millions of workers have lost their jobs; output has contracted at a rate not seen since the Great Depression; and governments have been forced to borrow trillions of dollars to support their economies. Yet, the stock markets have rebounded in a way that does not correlate with what is happening in the real economy.

According to The Economist, “between February 19th and March 23rd, the S&P 500 index lost a third of its value. With barely a pause it has since rocketed, recovering more than half its loss. The catalyst was news that the Federal Reserve would buy corporate bonds, helping big firms finance their debts. Investors shifted from panic to optimism without missing a beat.”

But this neat story should make you cautious. It is true that intervention by the Fed has driven real yields on many classes of bonds to negative territory, thus making stocks relatively more attractive. However, the stock-buying binge has been highly uneven, “investors have put even more faith in a tiny group of tech darlings—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft—which now make up a fifth of the S&P 500 index. There is little euphoria, just a despairing reach for the handful of businesses judged to be all-weather survivors.”

Indeed, the more we look into it, the more we see the beginnings of an asset bubble. Markets seem to be over-discounting the probability of another wave of infections and of any permanent damage to the economy. Not to mention the political repercussions of yet another bailout for large firms.

Perhaps most dangerous of all, the stock markets seem to be pricing in a quick “V” shape rebound in economic activity. Yet, as reviewed by the Financial Times, a study from the UK-based Institute for Fiscal Studies sets forth the reasons why an early return to normality is unlikely:

- “First, uncertainty will not disappear.

- Second, the impact of the virus on supply and demand for goods and services will be highly heterogeneous. On the supply side, work that demands face-to-face contact or co-operation will continue to be more affected than work that can be done at a distance. The same will be true of the pattern of demand.

- Third, the impact on the labor supply and on would-be purchasers is also going to be heterogeneous, with the young able to operate much as before and the older and those with health conditions far less so.

- Fourth, even this ignores the complex impact from the world economy.”

Finally, in the words of Martin Wolf, “people cannot just be ordered back to work and spending.” It is just unreasonable then to believe everything will return to the way it was before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Quote of the Day

“Man’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible; but man’s inclination to injustice makes democracy necessary.”

—Reinhold Niebuhr

Note from the editor

A friend recently shared with me a blog post by Howard S. Marks, the co-founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, entitled “Knowledge of the Future”. To my surprise, it was unexpectedly free of the usual bromides and platitudes put forth by investment managers. Indeed, it was a sharp critique of the way traders and financial analysts think.

According to Marks, “these days everyone has the same data regarding the present and the same ignorance regarding the future.” In that scenario, the usual human reflex is to look to the past for lessons, patterns, and cycles that may shed some light on the future.

But “blind faith in the relevance of past patterns makes no more sense than completely ignoring them. There has to be good reason to believe the past can be extrapolated to the future…it has to be informed extrapolation.” Which brings him to the U.S. today, where we are seeing:

- “One of the greatest pandemics to reach us since the Spanish Flu of 102 years ago;

- The greatest economic contraction since the Great Depression, which ended 80 years ago;

- The greatest oil-price decline in the OPEC era (and, probably, ever); and

- The greatest central bank/government intervention of all time.”

According to Marks, “the future for all these things is clearly unknowable. We have no reason to think we know how they’ll operate in the period ahead, how they’ll interact with each other, and what the consequences will be for everything else. In short, it’s my view that if you’re experiencing something that has never been seen before, you simply can’t say you know how it’ll turn out.”

Then he goes a step further. He states that it is his “conviction that there’s no ‘informed’ way to choose between the positive and negative scenarios we face today, and that most people decide in a way that reflects their biases. In other words, we may not be able to know the future, but that doesn’t keep us from reaching conclusions about it and holding them firmly.” And he is right.

Mr. Marks’s post brought to mind the five-year Fiscal Plan for the government of Puerto Rico just put out by the Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority (AAFAF, by its acronym in Spanish) and which I read a few days ago. Reading that document, I kept returning over and over to the same thoughts: “there is no way they can know this or whether X event will really happen”.

All that AAFAF and its consultants can do is more or less speculate according to their own biases, and lend that exercise a patina of sophistication with economic jargon, financial data, and fancy charts. But it is simply impossible to draft today a five-year plan in an “informed” or “knowledgeable” manner, at least not in the way we commonly use those words. The same epistemological difficulty applies, by the way, to the ostensibly highly-pondered analyses presented by the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico.

In sum, we should be reasonably skeptical about those who claim to have all the answers, either on the left or the right. Question everything. Accept radical uncertainty. And learn to live in the new environment.

Weekend Reading Recommendations

Here are some reading recommendations from the CNE team:

- Greil Marcus on Gatsby: A Blues Fable of the Great Depression – LitHub

- Margaret MacMillan on covid-19 as a turning point in history – The Economist

- The Coronavirus Won’t Usher in an American Welfare State – Foreign Affairs

- April 15, 2020:A Coronavirus Chronicle – The New Yorker

- Is It Safer to Visit a Coffee Shop or a Gym? – The New York Times

- Essential, and No Longer Disposable – The Atlantic

- Inside the Early Days of China’s Coronavirus Coverup – Wired

This is the end of today’s briefing.

Stay safe and well informed!