Published on October 8, 2020 / Leer en español

Dear Readers:

We continue our Focus 2020 series this week with a look at the Puerto Rico housing sector. The lack of affordable and safe housing has been a problem for decades on the island, which became critical after the 2017 hurricanes and the earthquakes earlier this year.

In an election year, you would imagine housing would be at the top of each candidate’s list of issues. And you would be wrong, by and large. With some notable exceptions, the issue is barely mentioned. This silence is quite puzzling as housing is a basic need for every human being. Indeed it is essential for wellbeing.

Fortunately, my colleagues Deepak Lamba-Nieves and Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, experts in urban planning, have been conducting research and analysis on housing issues in Puerto Rico as part of our Blueprint Housing and Land Initiative. We hope the analysis they present below stimulates debate and prompts some new thinking on this important topic.

—Sergio M. Marxuach, Editor-in-Chief

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Part IV – What is Land Value Capture?

In the fourth installment of our series, we analyze the land value capture theory as a way to improve municipal fiscal performance.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Improving Municipal Performance through Land Value Capture

By Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, Ph.D. – Research Associate, and Deepak Lamba Nieves, Ph.D. – Research Director

Question: How can the central government ensure that municipalities in Puerto Rico are able to overcome their fiscal challenges and provide quality public services and infrastructure?

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing post-disaster reconstruction, municipalities in Puerto Rico are facing increased fiscal constraints and the imposition of austerity measures. In its fiscal plans for the Commonwealth, the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (“FOMB”) has stated that transfers of funds from the central government to municipalities will be phased-out by 2024.

The FOMB is pushing municipalities to simultaneously compensate for this loss of revenue by substantially reforming Puerto Rico’s outdated property tax regime. While property taxation is an essential source of revenue for municipal governments and reforms have been talked about for many years, changes aimed at simply increasing tax revenues can have substantial regressive effects. When these reforms are combined with policies that seek to reduce deficits, they can end up seriously hampering the provision of quality public services and investments. One way to avoid this situation is by focusing on land value capture as part of a broader property tax overhaul.

What is land value capture (“LVC”)? As shown in simplified fashion in the diagram below, land value capture refers to a series of policy instruments that a local government can implement to “capture”—through taxation, fees, or acquisition—a fraction of the value that is added to development costs by way of speculation and market pricing. Once the added value is “captured”, local governments can redistribute it by making strategic investments in infrastructure improvements, affordable housing, or public amenities, prioritizing low-income households. Common instruments used for LVC include land value taxation, development impact fees, charges on building rights, community land trusts, and land banking.

TOTAL LAND VALUE AND LAND VALUE CAPTURE

Tools that facilitate LVC are quite common throughout the world, including many countries in Latin America and Europe. In cities like São Paulo, LVC tools provide essential resources for key urban improvement projects. Enrique Silva, director of international initiatives at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, discussed this case in a knowledge exchange hosted by CNE’s Blueprint Housing and Land Initiative. His presentation in Spanish can be accessed below:

Housing and Digital Platforms: Airbnb in Puerto Rico

By Raúl Santiago-Bartolomei, Ph.D., Research Associate

Airbnb’s entry into Puerto Rico, at least before the COVID-19 outbreak, had been very well received. This digital platform allows property owners to make their homes available for short-term rental. It has raised passions among supporters who defend the company as the standard for technological innovation, and detractors including hotel owners who allege that the competition is unfair and residents who claim that this technological platform reduces the availability of housing in their communities. Although there is much truth to the arguments of supporters and detractors, the evidence thus far appears to support the claims of detractors, particularly those of residents. However, even when it can be proven that Airbnb affects the availability of housing, addressing and regulating this situation poses an enormous challenge for local governments.

Airbnb and Digital Platforms

There is a romanticism about the economic possibilities offered by companies that provide digital platforms. These platforms are marketed as technological innovations that offer existing services more efficiently and at a lower cost, in turn causing disruptions in traditional markets. In turn, the argument is that these platforms allow any individual to access additional income by making use of their assets, be it a car or a home, to provide a service for public consumption. This dynamic, misnamed the “sharing economy”, since it there is very little sharing and does not come from a collective effort on the part of users, has instead been led by multinational companies that have abundant venture capital, which has afforded them a huge advantage to enter all kinds of markets around the world. Airbnb definitely falls within this group of companies and has managed to establish itself in international short-term rental markets.

Data Snapshot

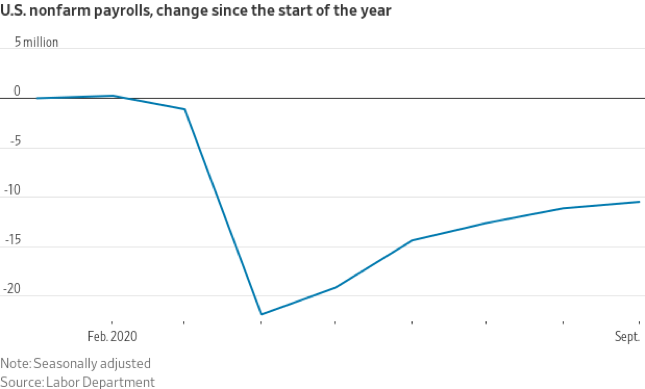

Job Gains Slow Down in the U.S.

Source: Data – Bureau of Labor Statistics; Graphic — The Wall Street Journal

Job growth in the United States slowed down significantly during September. According to reporting from the Wall Street Journal, “U.S. hiring gains slowed to 661,000 in September, suggesting labor-market improvements from the coronavirus downturn are moderating. The unemployment rate fell to 7.9%. The economy has now recovered 11.4 million of the 22 million jobs lost in March and April at the beginning of the pandemic, the Labor Department said Friday. Job growth, though, is cooling, and September marked the first month since April that net hiring was below 1 million.”

The bottom line of the last employment report before the elections is that there are currently close to 11 million fewer jobs than before the pandemic. And “at the current pace, it will take more than 16 months to recoup those losses, the pain is particularly acute in low-wage, service-sector jobs and the risk of permanent damage is increasing.”

On Our Radar...

![]() Housing Prices Continue to Rise, Despite Pandemic – “House prices picked up in most middle- and high-income countries in the second quarter. In the rich world they rose at an annual rate of 5%. Share prices of developers and property-traders fell by a quarter in the early phase of the pandemic, but have recovered much of the fall,” according to reporting by The Economist. They attribute this phenomenon to three factors: monetary policy (low-interest rates); fiscal policy (income support for families); and changing preferences (people are more willing to invest more in housing now that they spend more time at home).

Housing Prices Continue to Rise, Despite Pandemic – “House prices picked up in most middle- and high-income countries in the second quarter. In the rich world they rose at an annual rate of 5%. Share prices of developers and property-traders fell by a quarter in the early phase of the pandemic, but have recovered much of the fall,” according to reporting by The Economist. They attribute this phenomenon to three factors: monetary policy (low-interest rates); fiscal policy (income support for families); and changing preferences (people are more willing to invest more in housing now that they spend more time at home).

![]() A Failure of Empathy – Understanding the depth and impact of a large number of deaths is difficult for most people, writes Olga Khazan in The Atlantic. In the case of the United States, the 200,000 deaths caused by COVID-19 are only exceeded by the Civil War, the 1918 Flu Pandemic, and the Second World War. Yet, according to Khazan, “there’s an additional explanation for this empathy deficit: Part of the reason this majority-white, majority-non-elderly country has been so blasé about COVID-19 deaths is that mostly Black people and old people are dying. Eight out of 10 American COVID-19 deaths have been among people older than 65; the rest of the dead are disproportionately Black…Segregated neighborhoods have also helped insulate white Americans from the horror Black Americans face, because the ambulance sirens and the packed hospital wards are typically far from their own zip codes.”

A Failure of Empathy – Understanding the depth and impact of a large number of deaths is difficult for most people, writes Olga Khazan in The Atlantic. In the case of the United States, the 200,000 deaths caused by COVID-19 are only exceeded by the Civil War, the 1918 Flu Pandemic, and the Second World War. Yet, according to Khazan, “there’s an additional explanation for this empathy deficit: Part of the reason this majority-white, majority-non-elderly country has been so blasé about COVID-19 deaths is that mostly Black people and old people are dying. Eight out of 10 American COVID-19 deaths have been among people older than 65; the rest of the dead are disproportionately Black…Segregated neighborhoods have also helped insulate white Americans from the horror Black Americans face, because the ambulance sirens and the packed hospital wards are typically far from their own zip codes.”

![]() “There’s No Going Back to Normal. There Was Never Any Normal to Return To.” – Says author Karen Russell in this interview for Esquire magazine. According to Russell many people “have a kind of nostalgia for the world before 2016. But the conditions for these present emergencies were well underway at that time. We had environmental catastrophes. We knew we were headed toward climate emergencies. We knew we had this broken, for-profit health care system. We knew we had a media empire with financial incentives to keep people glued to screens filled with distorted information. But there’s no going back to normal. There was never any normal to return to, so we’re going to have to figure out a way forward.” What do you, our reader, think?

“There’s No Going Back to Normal. There Was Never Any Normal to Return To.” – Says author Karen Russell in this interview for Esquire magazine. According to Russell many people “have a kind of nostalgia for the world before 2016. But the conditions for these present emergencies were well underway at that time. We had environmental catastrophes. We knew we were headed toward climate emergencies. We knew we had this broken, for-profit health care system. We knew we had a media empire with financial incentives to keep people glued to screens filled with distorted information. But there’s no going back to normal. There was never any normal to return to, so we’re going to have to figure out a way forward.” What do you, our reader, think?