Published on May 27, 2021 / Leer en español

In This Issue

We present the latest iteration of our newsletter: the CNE Review. As the COVID-19 pandemic slowly recedes from our lives (and the headlines) we think a monthly format for our newsletter is more in line with our core mission of thorough policy research and analysis. It will also allow us to provide you with a broader, wide-angle perspective on a single issue or topic per month in a useful, and we hope effective, format.

In the coming months, you will be able to read our analysis of important issues for the future of Puerto Rico in areas such as economics, energy, housing, debt restructuring, hurricane reconstruction, federal affairs, and of course, the continuing pandemic, among other subjects. We are eager to share our insights and interpretations with you. In the meantime, keep well and thank you for your support.

Insights + Analysis from CNE

Taking Stock of Puerto Rico’s Reconstruction Process

By Sergio M. Marxuach, Policy Director

It has been about three years and eight months since Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. It is as good a time as any, to take stock of the post-storm reconstruction and recovery process as we approach the beginning of yet another hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean.

According to official estimates, Hurricane Maria caused approximately 3,000 deaths and about $90 billion in damages. The ineffective initial response from both the Puerto Rico and federal governments, exposed long-existing economic, political, and social inequalities, as well as Puerto Rico’s subordinated standing in the United States’ political system. Eventually, Congress approved part of the funding required for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction, but in many cases with highly prescriptive conditions and requirements that have unduly delayed and burdened the reconstruction process.

Keep reading for a summary of our policy brief. Click here to access the full text.

The Federal Appropriations Process and Disaster Assistance

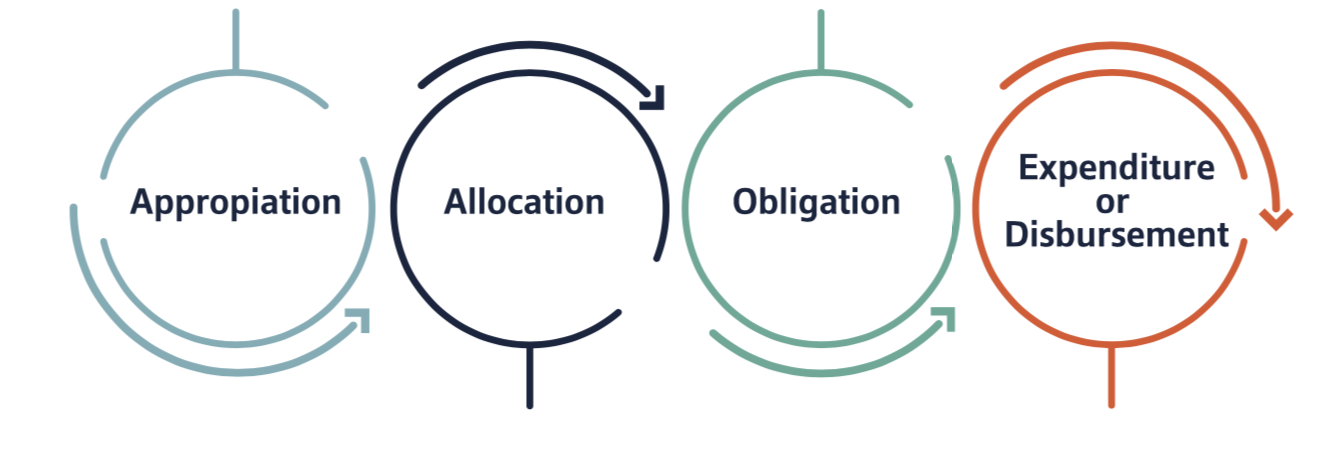

Congress makes decisions about spending specific funds through a complicated “appropriations process.” The key concepts to understand in this process are:

Federal Disaster Funding Update

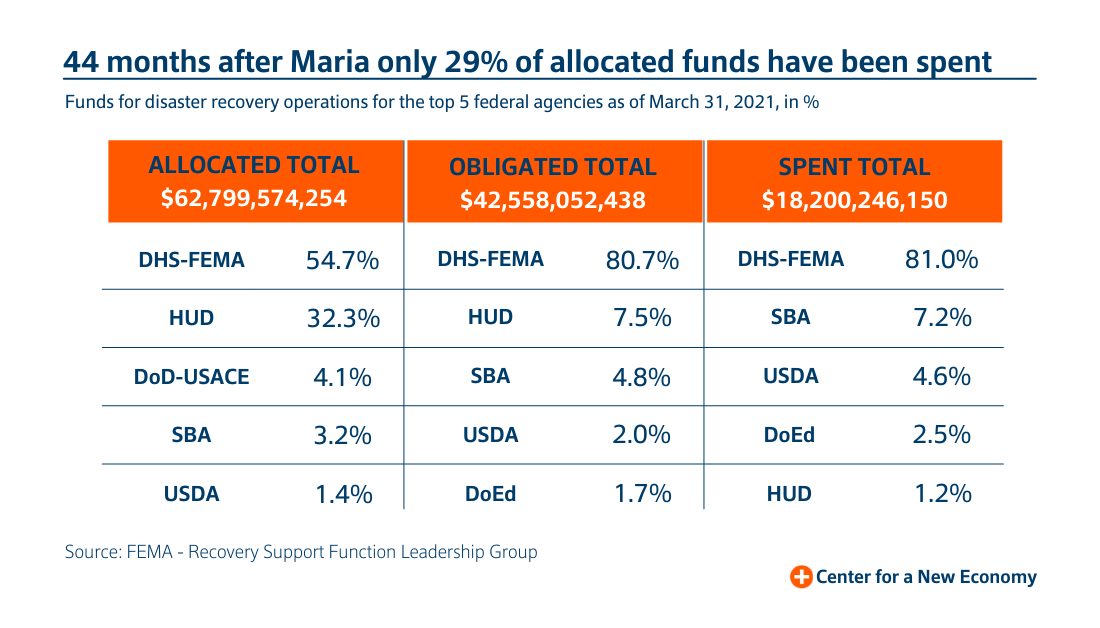

A total of seventeen federal agencies have allocated funds for disaster recovery operations in Puerto Rico since 2017. The table below summarizes the total funds allocated, obligated and outlayed or spent by the top five agencies in each category as of March 31, 2021.

Management of Disaster Assistance Funds

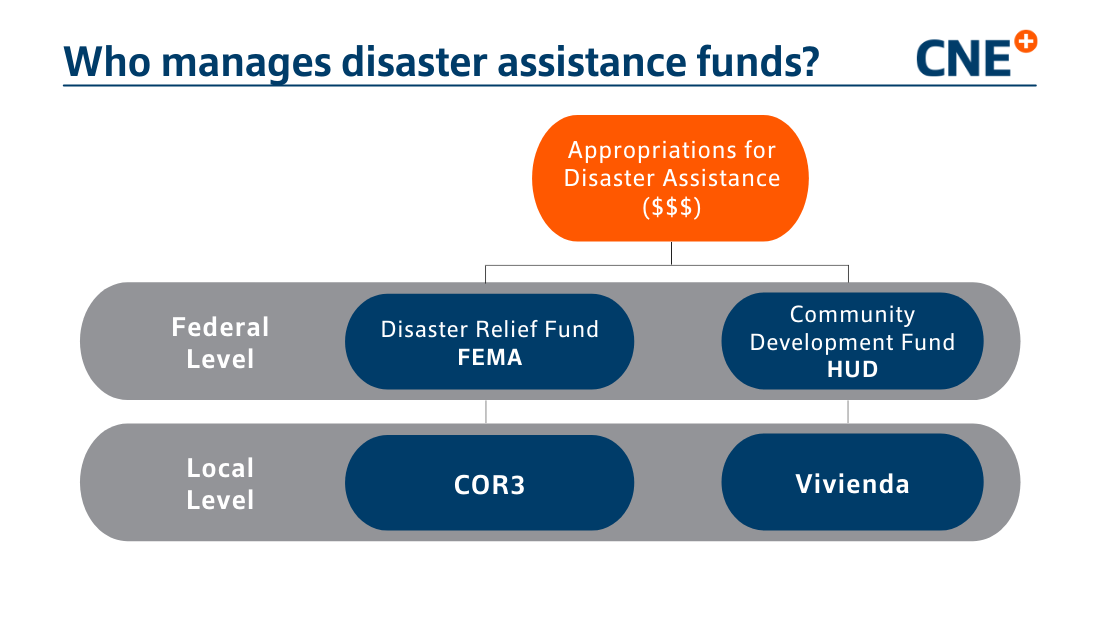

In the case of appropriations for disaster assistance, the federal government operates through two principal “master accounts” and four main agencies: the Disaster Relief Fund managed by FEMA, who works with the Puerto Rico Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction, and Resiliency (“COR3”) to manage its assistance programs in the island; and the Community Development Fund, managed by HUD, which finances the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (“CDBG-DR”) program and works with the Puerto Rico Housing Department (“Vivienda”) to administer CDBG-DR programs in Puerto Rico.

FEMA

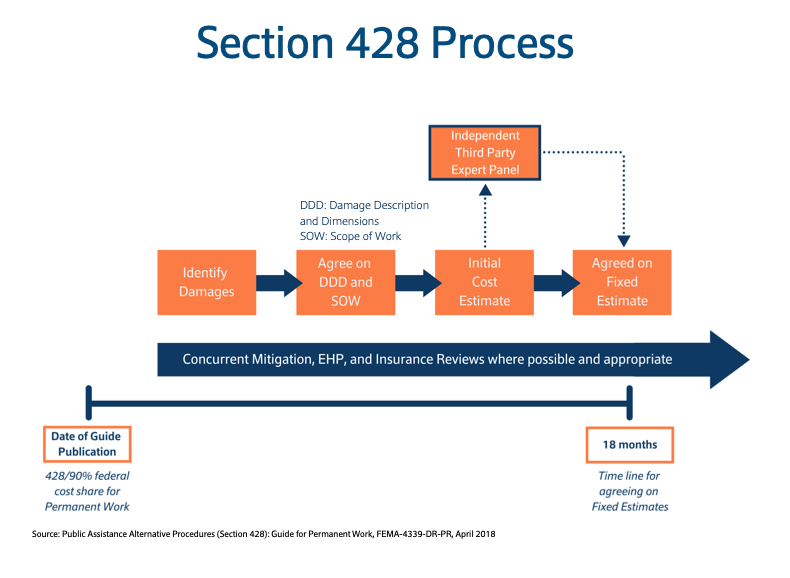

The slow disbursement of funds for permanent work public assistance projects has been the main focus of contention between FEMA and COR3 for three years now. The delay in disbursing these funds can be partially attributed to the decision by FEMA and the government of Puerto Rico to use an alternative process for the disbursement of these funds, following Section 428 of the Stafford Act; a process which is not as streamlined as might be at first thought:

In practice, the Section 428 process has turned out to be unduly bureaucratic, drawn-out, and, in our view, has failed to meet its programmatic objectives. This process for approving permanent work projects under Section 428 was supposed to take 18 months from the date of publication of the guidelines for these projects, in April of 2018, a deadline that has been extended several times, most recently to December 31, 2021.

HUD & CDBG-DR Funds

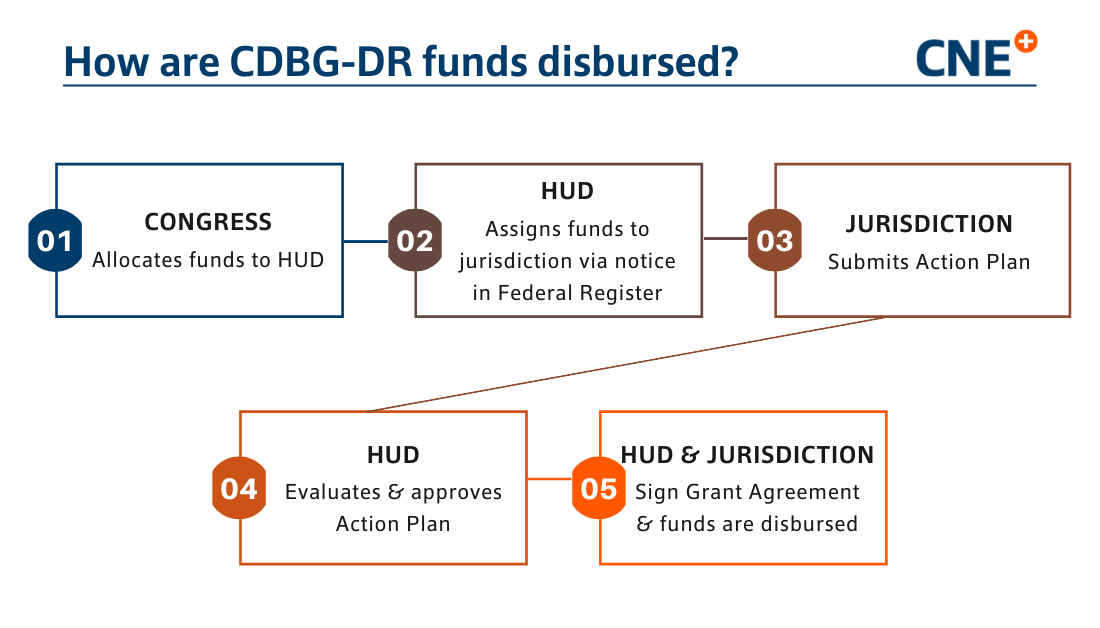

The chart below summarizes the somewhat cumbersome process for disbursing Community Development Block Grant (“CDBG-DR”).

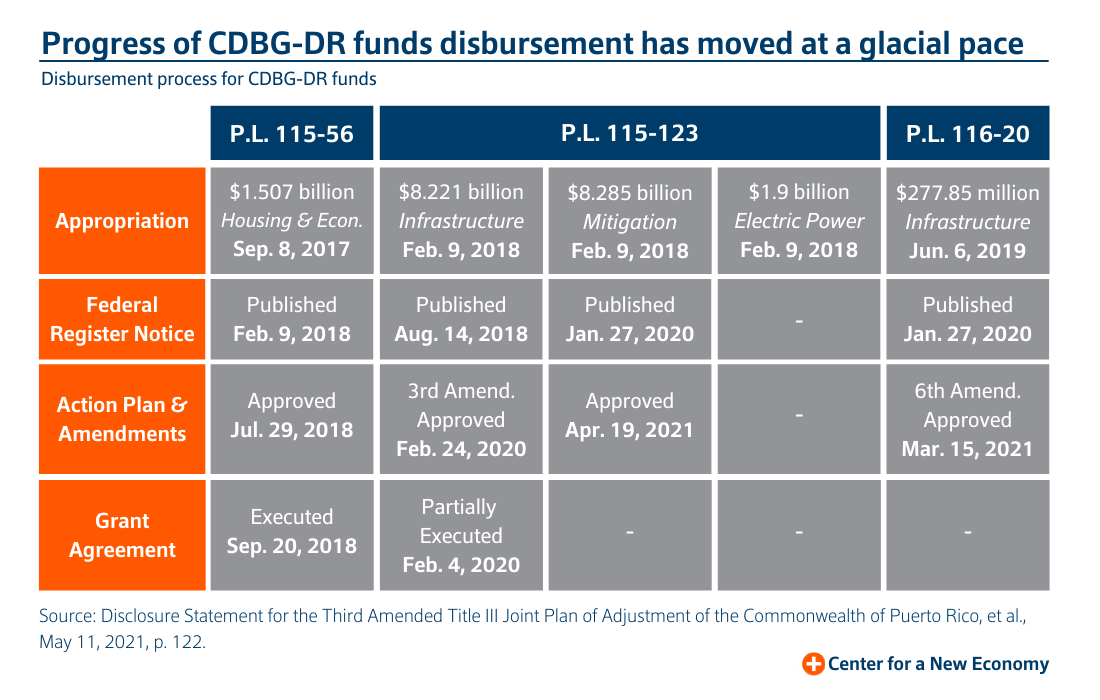

Between September 2017 and June 2019, Congress appropriated approximately $20.3 billion in CDBG-DR funds for disaster reconstruction and mitigation activities related to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico through three supplemental appropriation acts:

- P.L. 115-56: $1,507,179,000 for unmet needs (a significant portion of these funds was used for the Home Repair, Reconstruction, or Relocation Program, also known as R3);

- P.L. 115-123: $10,153,130,000 for unmet needs (including $1.9 billion to enhance and modernize the electric grid) and $8,285,284,000 for mitigation activities; and

- P.L. 116-20: $304,000,000 for unmet needs.

The table above provides an overview of the process for disbursement of CDBG-DR funds and where the process currently is for each of the supplemental appropriation acts made into law between September 2017 and June 2019.

Click to know more about the CDBG-DR disbursement process and why it has taken so long.

Finally, Funding is Important, but…

The reconstruction of Puerto Rico and the economic recovery and growth tied to that reconstruction have been slower than initially anticipated. However, obligating and spending the federal funding assigned for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction and recovery is only one part of that process. The sequence of events we call “Hurricane Maria”, and their consequences, have their roots in multiple decisions that were made decades ago.

The damage caused by Hurricane Maria cannot be attributed solely, or even primarily, to the meteorological event. The question for Puerto Rico is, then, are we going to build back in a way that replicates those vulnerabilities? The answer to that question, in turn, raises other rather problematic political questions. Who and how do we decide to spend this federal windfall? What do we preserve, what do we leave to waste, and who decides? Who is deemed “worthy” of help, why, what kind, and from whom? For instance, Which coastal community gets a seawall and which community is relocated to a “safer area”?; Whose neighborhood gets razed to the ground, displaced, or gentrified in the name of “redevelopment”?; Where do we build new public schools, hospitals, and electric, water, and telecommunications infrastructure, and who decides?

In the end, then, the shape of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria will depend to a large extent on how we address long-standing issues of class, race, segregation, poverty, inequality, and political power that we have ignored for far too long.

On Our Radar...

![]() Global Downward Mobility – “A new Pew Research Center analysis finds that the global middle class encompassed 54 million fewer people in 2020 than the number projected prior to the onset of the pandemic. Meanwhile, the number of poor is estimated to have been 131 million higher because of the recession. The drop-off in the global middle class was centered in South Asia and in East Asia and the Pacific, and it stalled the expansion seen in the years preceding the pandemic. South Asia, specifically India, along with Sub-Saharan Africa, accounted for most of the increase in poverty, reversing years of progress on this front.”

Global Downward Mobility – “A new Pew Research Center analysis finds that the global middle class encompassed 54 million fewer people in 2020 than the number projected prior to the onset of the pandemic. Meanwhile, the number of poor is estimated to have been 131 million higher because of the recession. The drop-off in the global middle class was centered in South Asia and in East Asia and the Pacific, and it stalled the expansion seen in the years preceding the pandemic. South Asia, specifically India, along with Sub-Saharan Africa, accounted for most of the increase in poverty, reversing years of progress on this front.”

![]() A New Concert of Great Powers – “The international system is at a historical inflection point. As Asia continues its economic ascent, two centuries of Western domination of the world, first under Pax Britannica and then under Pax Americana, are coming to an end. The West is losing not only its material dominance but also its ideological sway. Around the world, democracies are falling prey to illiberalism and populist dissension while a rising China, assisted by a pugnacious Russia, seeks to challenge the West’s authority and republican approaches to both domestic and international governance.” According to Richard Haas and Charles Kupchan, writing in Foreign Affairs, “the best vehicle for promoting stability in the twenty-first century is a global concert of major powers. As the history of the nineteenth-century Concert of Europe demonstrated—its members were the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Prussia, and Austria—a steering group of leading countries can curb the geopolitical and ideological competition that usually accompanies multipolarity.”

A New Concert of Great Powers – “The international system is at a historical inflection point. As Asia continues its economic ascent, two centuries of Western domination of the world, first under Pax Britannica and then under Pax Americana, are coming to an end. The West is losing not only its material dominance but also its ideological sway. Around the world, democracies are falling prey to illiberalism and populist dissension while a rising China, assisted by a pugnacious Russia, seeks to challenge the West’s authority and republican approaches to both domestic and international governance.” According to Richard Haas and Charles Kupchan, writing in Foreign Affairs, “the best vehicle for promoting stability in the twenty-first century is a global concert of major powers. As the history of the nineteenth-century Concert of Europe demonstrated—its members were the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Prussia, and Austria—a steering group of leading countries can curb the geopolitical and ideological competition that usually accompanies multipolarity.”

![]() Statelessness and Citizenship – “If all the stateless people on earth were to form a nation, its population would exceed that of Sweden, Greece, Azerbaijan, or New York City—possibly by a large margin. Some 10 million people worldwide lack citizenship, according to the United Nations, which makes them exceptionally difficult to count. Those not recognized by any state tend to be left off censuses, benefit rolls, and other official registers. Governments have few incentives to acknowledge the stateless residents within their borders. Stateless people do not elect officials, enjoy diplomatic representation, or possess the lucre of a corporate lobby. Without political rights they can exert only so much pressure; activist groups, charities, and NGOs are their main source of support…” writes Atossa Araxia Abrahamian in this interesting analysis for the New York Review of Books.

Statelessness and Citizenship – “If all the stateless people on earth were to form a nation, its population would exceed that of Sweden, Greece, Azerbaijan, or New York City—possibly by a large margin. Some 10 million people worldwide lack citizenship, according to the United Nations, which makes them exceptionally difficult to count. Those not recognized by any state tend to be left off censuses, benefit rolls, and other official registers. Governments have few incentives to acknowledge the stateless residents within their borders. Stateless people do not elect officials, enjoy diplomatic representation, or possess the lucre of a corporate lobby. Without political rights they can exert only so much pressure; activist groups, charities, and NGOs are their main source of support…” writes Atossa Araxia Abrahamian in this interesting analysis for the New York Review of Books.